For Ukrainians, the ancient name of Aeneus is like a kick starter of an efficient engine; they are instantly reminded of these opening lines:

“Aeneas was a lively fellow,

Lusty as any Cossack blade,

In every kind of mischief mellow,

The staunchest tramp to ply his trade.”

(Trans. by C. H. Andrusyshen and Watson Kirkconnell)

There is probably no other nation with a greater affection for this hero, the son of Venus and the Trojan prince Anchises. At the same time, it is unlikely that most Ukrainians identify their Ankhyzenko with the great Virgil’s Aeneas.

The history of world literature knows numerous examples of national burlesque versions of Virgil’s Aeneid. “‘Travesties’ of Virgil’s Aeneid were the most popular among numerous burlesques of the baroque period” (Dmytro Chyzhevsky).

Travesty, which is a special kind of burlesque, emerged in the 17th- 18th centuries. This type of work features a “high” theme rendered in “low” language and style. At the time, a more elevated level than Virgil could not be found. Even Homer, whose style Virgil emulated, was for several centuries (even during the Renaissance) overshadowed by his celebrated successor. It is not surprising, then, that European literati would try to hone their baroque skills by studying Virgil’s masterpiece. The French writer Paul Scarron won the greatest acclaim, and his poem Virgil travesti (“Virgil rendered topsy- turvy”; 1649-52) became a classic of the genre. This classic was followed, among others, by Andreas Blumauer. His German-language version of the Aeneid (an enlightening satire of church piety) was read by the Russian Nikolai Osipov and Aleksandr Kotelnitsky. Emulating the Austrian’s travesty, they turned Virgil’s original creation inside out, the Muscovite way: Aeneid turned inside out by Nikolai Osipov, Parts 3-4 (1794); by Aleksandr Kotelnitsky, Part 6 (1806).”

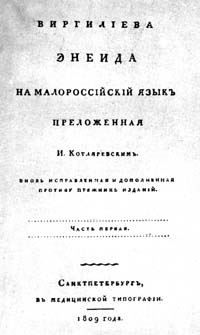

According to several distinguished philologists of Moscow State University (http://shadow.msu.ru/rus/kaf /tlit/sem/cont/iroicomi.html), “The Aeneid, travestied by Osipov, exerted an influence on the Ukrainian writer I. Kotliarevsky, who published his Little Russian version of the Aeneid in St. Petersburg in 1798. Kotliarevsky’s poem won acclaim as yet another eloquent example of travesty cultivated on Slavic soil.” (It should be noted that the 1798 edition was published without the author’s knowledge and consent. The title page read, “Aeneid rendered in Little Russian by I. Kotliarevsky with the permission of the Central Censorship Office of Saint Petersburg. Financed by M. Parpura. Printed in St. Petersburg, 1798.” The edition that the author prepared himself appeared in print in 1809. The title page contained the inscription Virgil’s Aeneid, rendered in Little Russian by N. Kotliarevsky (St. Petersburg. Medical Print Shop, 1809). The phrase “exerted an influence” is as inadequate as placing Kotliarevsky’s Eneida on a par with other travesties (“another eloquent example,” as Osipov put it). Unlike Scarron, Blumauer, or Osipov, Ivan Kotliarevsky did not intend his Aeneid as a travesty of Virgil’s masterpiece. The founder of classic Ukrainian literature simply “transposed” the Russian version of the Aeneid into his native tongue. Mykola Zerov notes, “From the first lines of Kotliarevsky’s poem it becomes clear that this work is not an entirely original one; that its concept, plot, and even creative devices have been borrowed from a work written in a different language...Even a cursory glance is enough to reveal that Kotliarevsky’s Ukrainian Eneida is largely dependent on Russian versions, specifically Osipov and Kotelnitsky’s... All the key episodes in Virgil’s poem are retold in keeping with Osipov’s poem; there isn’t a single Virgilian feature that he could have introduced in his narrative independently of the Russian Aeneid, with regard to one scene or another. However, there are also individual expressions, comparisons, apt aphorisms, accurate observations, merry “coinages,” and “macaronic” word combinations — quite a few of them attributed to Kotliarevsky’s stylistic talent. Yet much that is credited to Kotliarevsky’s stylistic talent is often revealed to be an ordinary translation from Osipov” whose work, in Zerov’s opinion, is a “popular, lively work, broadly outlined and realized for its time, even if it is not a first-rate literary accomplishment.”

Surprisingly, Osipov and his travesty — which was a vivid example and even the model for Kotliarevsky, as it turned out — sank into oblivion, relegated to specialized textbooks and figuring on lists of rare editions. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian follower of the brilliant Russian author remains very much alive. As for the Russian version of the Aeneid, it is largely regarded as a parody of the original masterpiece.

“Enei was a smart lad,

And the most dashing of fellows.”

Is this not reminiscent of the elaboration of a “high” Ukrainian theme in “low” language and style?

“In Russian literature, as in other European literatures earlier, the poetic travesty recedes to the periphery of literary genres, remaining an historical form with a limited literary life span” (this, again, from the Moscow State University philologists). But in Ukrainian literature Kotliarevsky’s poem has overcome the boundaries of time — and not by a marginal devotee of chimerical (baroque) Ukrainian old-world realities but the founder of modern Ukrainian literature.

“My father, you will rule

For so long as people live;

For so long as the sun shines

They will keep remembering you!”

In the two centuries of its existence, Kotliarevsky’s Eneida has been subjected to a whole range of critical attitudes: “In Eternal Memory of Kotliarevsky” and “burlesque in the Muscovite style” (Shevchenko); “his language, correct, sparkling, and national to the highest degree, will remain the finest monument...” (Kostomarov); Kulish’s accusations of renegade attitudes (“...he is twisting Ukrainian words...the very idea of writing a parody in the language of his people shows a lack of respect for that language”); Zerov’s reproaches that Kotliarevsky did a linear translation; Shevchuk’s comment that “the structure of I. Kotliarevsky’s Eneida is very sophisticated and complex, while the system of subtexts and extratextual references is remarkable.”

On the centenary of Kotliarevsky’s birth, Maksym Rylsky wrote, “The importance of the author of Eneida should not be exaggerated... we should not paste on him the inaccurate label of courageous radical, almost a revolutionary.” One would like to believe that the Soviet Ukrainian poet was trying to preserve Kotliarevsky for the future of Ukrainian literature, “which is flourishing so wonderfully in our sunlit days, among other literatures” (1938). Today, therefore, those who are “weighing” the components of the process of building the Ukrainian national idea should not underestimate the importance of the author of the Eneida.

The scholar, Mykola Zhulynsky, is absolutely correct when he compares Petrarch and Kotliarevsky: “ Eneida is a careful, but conscious, goal-oriented [work] cloaked in a subject from antiquity, [it represents] the extraction of Ukrainian culture from the imperial, ideologically regulated ‘order,’ from that regulated Russian language and the state church of ‘all-Russian unity’ and the imperial cultural model... In the period of national division, the intense suppression of national dignity, the ban on the Ukrainian word, [and] the alienation of a significant part of the national elite from its own people, the need for a hero who could inspire hope, lift social moods, gladden the national spirit, and express state thinking was felt with particular acuteness.” Likewise, Petrarch wrote his heroic epic poem Africa in order to “awaken national consciousness and to instill a spirit of unity in Italians by reviving the republican ideals and historical memory of Rome’s might.” The Roman poet considered his work to be a latter-day version of the Aeneid (he even wrote it in Latin and hoped to be rewarded with a laurel wreath). Yet the poem “never became an Italian national epic, although Petrarch chose Virgil’s Aeneid as a model,” notes Zhulynsky. The Little Russian version of Virgil’s Aeneid did.

Virgil’s work is as surprising as Kotliarevsky’s. The latter’s masterpiece does not fit the classical heroic epic model in which a downtrodden or suffering people finds consolation in the memories of its glorious past. According to this model, the Hetmanate in Kotliarevsky’s time, Italy in Petrarch’s time, even Greece in Homer’s time, regularly produce geniuses. But did Rome during the Principate? Did this world power, the “sole Cosmopolis of the inhabited earth,” the Eternal City, need the dubious delight that those who are currently oppressed and humiliated would find in the distant future?

If Roman virtue is measured only by military valor, then the answer is no, it did not. The Romans, however, showed valor not only on the battlefield; they were as determined to show their attainments in the cultural realm. After conquering Greece by military force, they not only mustered the courage to submit to the Hellenic cultural genius, but also to challenge it. “Scorned” and “humiliated” by Homer, the Roman poet Virgil launched a counteroffensive, asserting in the realm of heroic poetry the spiritual valor of the Roman Quirites. Other representatives of the Roman cultural cohort acted along other lines. This offensive proved so strong that centuries ago the Greek poet Plutarch launched a counterattack with his Parallel Lives. As the result of this grand agon between the two ancient Greek and Roman peoples, we have this great Greco-Roman culture as the foundation of European culture.

Virgil’s awareness of his Roman dignity led him to challenge the Greek giant Homer. Driven by the sense of his people’s national dignity — and “Kotliarevsky was the first captive of Ukrainian folk culture” (Yevhen Sverstiuk)” — the author of Eneida challenged the Russian giant and stood up to “that inexorable avalanche rolling from the north to the Black Sea, covering everything that bore a Russian name with the identical shroud of slavery” (Alexander Herzen).

Humor — live, sparkling, hot, even with red pepper — would best serve against the northern avalanche. Kotliarevsky’s “spiced up” style, however, has nothing to do with “tavern speech” (Kulish’s jibe). It has preserved a sense of personal dignity and that of his people, which is germane to the author of Eneida. “Ivan Kotliarevsky is always consistent in championing national dignity, cultural independence, and pride” (Sverstiuk). It is like the typical irony of the British, which they direct at themselves, like the Spartans’ ability to endure mockery of themselves (Plutarch said that one of the main Spartan virtues was the ability to calmly endure mockery).

Once you forget about your dignity, you will have “Kotliarevshchism” whose “dirty gray shadow hung over the poet’s lofty name; any slavish mediocrity, brutally inheriting the Eneida, actually parodied its folk humor and reduced its simplicity to that primitive Little Russian vernacular... designed to entertain with a Ukrainian language rendered by a buffoon who does not even amuse a king but a marketplace crowd.” In addition to that 19th-century prattle, Yevhen Sverstiuk remembers Soviet Ukrainian authors, such as Ostap Vyshnia, the magazine Perets (Pepper), Tarapunka, and other comic writings of the twentieth century, whose “national character outsiders [identify] with a low cultural level and mossy primitivism.” (Today, the baton in the “Kotliarevsky” relay race is carried by the “Rabbits” [Ukrainian comedians Volodymyr Danylets and Volodymyr Moiseyenko, who use a mixture of primitive Ukrainian and Russian] and Verka Serdiuchka [a male comic posing as a buxom Ukrainian conductress, who uses the same kind of jargon, especially popular on Russian TV]).

Once you forget dignity, Kotliarevshchysm will get to you. You will start picketing concerts starring Serdiuchka (and s/he will then complain about nationalistic attacks). You will be outraged instead of ignoring him/her the Spartan way.

Mykola Zerov was wrong when he said that “in general, everything we find in Virgil’s Aeneid is specifically Roman, constituting the Roman soul; its patriotic idea, archaeological discourses, and genealogical assumptions — all this is in no way echoed by Kotliarevsky.”

Honor and dignity, patriotism and nationalism — these aspects distinguish Virgil and Kotliarevsky’s works in the first place, while uniting them and their authors. These are moral, cultural, and lasting factors. Is this why we now have two Aeneases who are very much alive today, Virgil’s classical and Kotliarevsky’s folk hero?

“...Such is my will,

For as far as my eye can see,

I shall build cities everywhere.”

“His goal...is to revive the past glory of Slavic Troy — e.g., Kyiv, the devastated cultural and religious capital of the Christian world; to restore the lost homeland” (Mykola Zhulynsky).