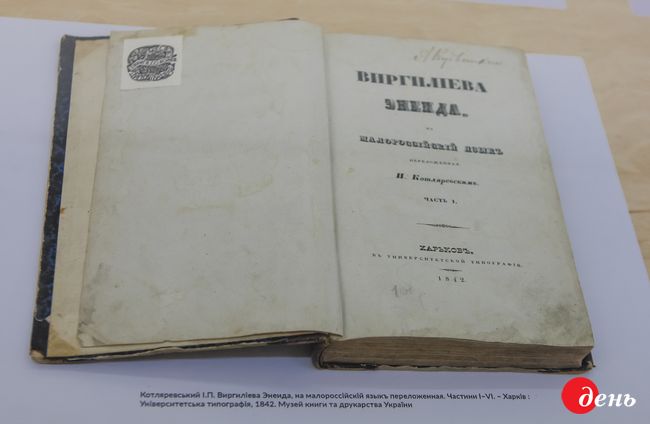

For more than two centuries, Ukrainians have been trying to unravel the riddles of Ivan Kotliarevsky’s The Aeneid. In most cases, researchers try to decipher the text: for example, they see Dido as a metaphor of Poland, and her self-immolation is interpreted as a reflection of the Swedish Deluge of the 17th century. However, in order to truly understand the significance of the poem, it is worth considering one more representation code of this work, the visual one. This was done by the exhibition “Project Aeneid.”

In general, the “Project Aeneid” is an example of a new format for cultural events. This event went beyond the exhibition and became a large-scale project aiming to make the Ukrainian past relevant again.

Pavlo HUDIMOV, who was the co-curator of “Project Aeneid,” talked to The Day about the “exhibition-book” technique, the evolution of Aeneas from a peasant to a hero, and the need to think in terms of glocalization.

“We are talking about Kotliarevsky not through the language of literature, but through that of visual history. This idea took a lot of effort to form. First, the Ya Gallery together with FILM.UA held ‘The Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors’ exhibition past year. This was the first shot at an ambitious project that worked with the past.

“One of the heroes of that project was the film’s artist Heorhii Yakutovych. Subsequently, he also illustrated the book The Shadows of Unforgettable Ancestors. And this was how it all started. Polina Limina, one of the project’s co-curators, penned the book Like in the Shadow. I became her fellow compiler. There, we had a broader look at the contexts that lie beyond the known plane.

“With the help of Serhii Yakutovych, we located the Carpathian archive of Heorhii Yakutovych, his wonderful sketches, and discovered several personal stories. One of the topics we target is the second half of the 1960s. Accordingly, we kept turning to the book which acquired the largest cult following at the time. This was The Aeneid with illustrations by Anatolii Bazylevych.”

“VISUAL INTERPRETATIONS”

“It became the starting point for thinking about how a 1960s and 1970s artist conceptualized poetic, textual subjects through the visual means, and made it relevant again. And we, with our team, began to work to understand where this phenomenon came from.

“The most interesting things started there. When working with Diana Klochko (who also joined the curatorial team of the ‘Project Aeneid’) on the book Bazylevych’s Aeneid at Artbook Publishing House, we also knew about the illustrations of Oleksandr Danchenko as well as the most famous work of Heorhii Narbut, Aeneas and His Host, and products of many other illustrators. However, we had no inkling that nobody ever reached this reservoir and collected it all in books or exhibitions. There are some studies dealing with illustrations to Kotliarevsky’s works, but The Aeneid gets little attention in them. Our team began to unravel the story, and it turned out to be infinite.

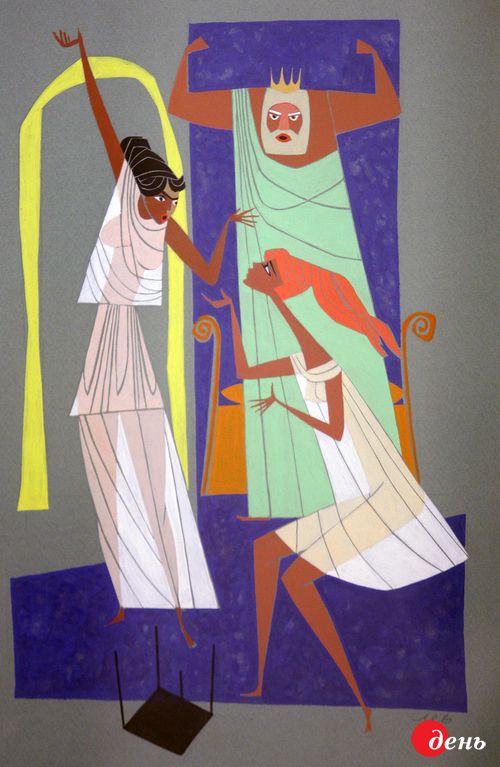

“There were a lot of subjects proposed for the exhibition. At some point, I said that we could just get lost there. Therefore, we limited it effectively to one subject, it being visual interpretations of The Aeneid and dialog with other artistic works of a certain direction and period. We also touched upon the themes that emphasized and stressed matters that we could not address in another way – for example, a 18th century Last Judgment icon and the infernal series of illustrations by Bazylevych.

THE FIRST ILLUSTRATIONS TO THE AENEID BY PORFYRII MARTYNOVYCH. HE DID 13 DRAWINGS IN 1873-74

“The fourth curator was Danylo Nikitin, who heads the graphic arts collection at the National Museum. We began to collect subject-related exhibits in museums in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Poltava, Lviv, and in private collections. The exhibition and catalog were sponsored by the Zahorii Family Foundation, and we organized the project in cooperation with the National Art Museum and the Ya Gallery...

“I have been using the exhibition-book technique for a long time. Therefore, I first came up with the idea of the catalog itself (chronology, a set of visual materials, breakdown into periods). Having made a book, we practically realized everything in the museum venue together with the designer Kateryna Sivachenko.

“In addition to the exhibition, there are many events in the parallel program, including The Endless Travel or Aeneid show by the agency ArtPole, where Yurii Andrukhovych reads The Aeneid and his essays to musical and visual accompaniment. The museum seemed to fly up to 10 meters above the ground when it all happened. We also have the space cafe Aeneas which hosts most events of the program, and a pop-up cafe hosted by Dmytro Borysov on weekends. In addition, there is the Project Aeneid train running on the blue line of the subway.

IVAN YIZHAKEVYCH, FEDIR KONOVALIUK, VENUS ON THE WAY TO NEPTUNE, 1948

“Thus, this exhibition has become a real project. And the catalog is its most important product; it will stay with us for a long time, while everything else will be removed from the walls, it will be removed from the glass cases and go back to 11 museums and 6 private collections. However, the catalog will be a reminder of what we have collected, analyzed, and most importantly, passed the topic to the future. Because while the ‘Project Aeneid’ had a beginning, it is endless.”

You stated that the “Project Aeneid” offers history of interpretations. Can you tell us about the evolution of the image of Aeneas?

“After rereading The Aeneid afresh, I realized that the image of Aeneas was quite controversial. On the one hand, Kotliarevsky wants to show him as a hero, but on the other, he does not emphasize the heroic. The poem features Nisus and Euryalus, fighting to the last, and they are heroes. That is, Kotliarevsky’s hero must be a victim.

IVAN YIZHAKEVYCH. THE PORTRAIT OF IVAN KOTLIAREVSKY, 1948

“Aeneas, since he is the protagonist, has certain signs of ‘sterility.’ Perhaps this is why artists love Aeneas, but they always find an even more interesting hero for themselves. This is the main problem of interpreting the image of Aeneas. Perhaps the only one who has more or less coped with it is Eduard Kirych, who drew and directed The Aeneid cartoon and came up with the cartoon image in 1991.”

“A HERO WHO COMBINED ALL CULTURES IN HIMSELF”

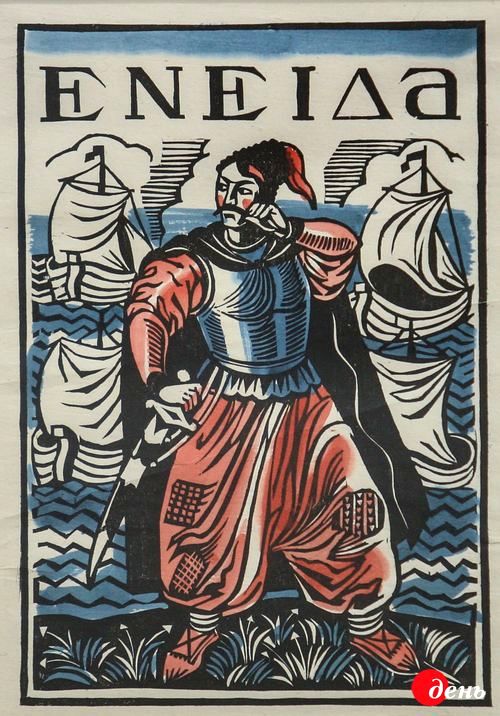

“Another interesting moment is how this image varies. In Narbut’s 1919 version, Aeneas looks delicate, with beautiful shiny eyes, without mustache. He is not like Aeneas the Cossack. Meanwhile, the 1910 poster for Mykola Lysenko’s opera depicts Aeneas as an Arab – dark-skinned, with Oriental, Arabic slanted eyes. The same image we see in Myron Levytsky’s 1963 work – a dark-haired Arab with beautiful eyes. That is, he was not necessarily similar to a Ukrainian Cossack. This is a hero who combines all cultures.

“How the Ukrainians wished to see Aeneas was best represented by Bazylevych in the 1968 book. It is interesting that Volodymyr Yurchyshyn, who was the Aeneas model for the artist, is actually quite thin, but in the picture he turns into a true hero. That is, the hyperbolization of heroism occurs already at the time of interpretation. There is an entirely opposite view in the illustration of Porfyrii Martynovych, which shows Aeneas as an ordinary peasant.”

These images are interesting in the historical aspect. Aeneas the peasant, most likely, becomes a symbol of the populist stage of the formation of the Ukrainian nation. With the transition to the political stage, Aeneas is depicted as a Cossack, that is, part of the force that protects the statehood, which at that time began to crystallize. But how did it occur to you to combine such diverse exhibits, ranging from the 5th century BC finds to the cartoons of the late 20th century? Please tell us how you created the exhibition format.

“These are cultural layers. Lack of space has not allowed us to realize all plans. It was more important for us to find a spatial solution – a way to establish a dialog manner so that it was understood by a wide audience, a way to make a special aesthetic of space.

ANATOLII BAZYLEVYCH. A SKETCH TO THE IMAGE OF AENEAS, 1961

“This is because the role of design is very significant. You get a lot of information from it, these are codes of aesthetics. Modern exhibitions are not mere outlines laid on a table or hanging on the walls, they are always synthetic products. In our project, we pay special attention to visitors. The exhibition seeks to attract people to visit museums, projects, events.”

“‘PROJECT AENEID’ DRAWS A LINE AND EXPECTS NEW INTERPRETATIONS”

“So we do not overload it. Most of the texts are abbreviated, but still very capacious, accurate. Limina did a great work, she was responsible for most of the texts. She went even further and developed rules for perception aiming to destroy the stereotypes.

“We ourselves, while designing this project, did not think stereotypically. Almost all the curators admitted that they had high hopes for future interpretations of Kotliarevsky’s work. The ‘Project Aeneid’ draws a line and expects new interpretations.”

IVAN PADALKA. A COVER FOR THE POEM, 1931

In essence, the project gives The Aeneid a new meaning, makes it possible to see it from another perspective, not only as “the first work written in the folk language.”

“Of course. Hundreds if not thousands of people will reread The Aeneid after the exhibition and look at this work completely differently.”

An important task of the exhibition is making the past relevant again. Would you please share with us what results you have had in this field? How should we talk about the past?

“In fact, we are only just finding ways to work with the past, not everything works out right away. There are so many stereotypes around, while we want to get people to relax, reject the fundamental cliches that we have learned at school, and realize that there can be many takes on the text.

“After all, our audience was smaller than it could be just because of the way The Aeneid and our literature overall are taught at school. I even heard such statements: ‘Had school not succeeded in discouraging me, I might have come to the exhibition.’ However, everything is completely different at our exhibition. Here you will not see anything that was learnt in school. I am pleased that many groups of school-age kids have come and written ‘it was interesting,’ ‘funny pictures,’ ‘I did not expect such an event, I thought it would be boring.’”

“A REAL KALEIDOSCOPE WITH A STRONG CORE”

“It is easy to explain why The Aeneid is interesting, since this is the material in which you can express yourself. The Aeneid itself is not that prudish. Here, the artist can indulge in depicting eroticism and heroism (both in the Olympus and the Hell) and find plenty of directions for their version to exploit.

MYRON LEVYTSKY. 1963

“Each artist has a peculiar interpretation. Let us recall Mykola Butovych’s Venus depicted as a nude Hutsul girl or an incredibly strong work by Danchenko in his distinctive darkness technique. It is very gothic, I would say that it turned out to be almost fantasy-like, but in the style of ancient Greek black-figure pottery.

“When I look at the works of Danchenko, I understand that he designed the images with the utmost accuracy and rigor. This is illustration engineering at work. Of course, when we talk about Kirych with his animation, this is a completely different side of The Aeneid.

“So when they are presented on the same plane, you just do not know which way to look first. However, there is no sense of confusion. This is a real kaleidoscope with a strong core, laid in by Kotliarevsky who was a brilliant man whose story has so far been poorly studied.”

What do you think of Nikitin’s statement that The Aeneid has already done its part? Is this text important today?

“Nikitin said that The Aeneid was actually a lifebuoy in difficult times. Therefore, in his opinion, it does not have such an acute, instrumental significance at the present time, when we can enjoy freedom, democracy and develop ourselves. We needed to stick to it in the 19th century as well as the 1910s and 1960s. The Aeneid had to be fought for. Then, The Aeneid stood for freedom, Ukraine, dream.

“I partly agree and partly disagree with Nikitin’s statement. This is because after the events of the last four years, one reads The Aeneid quite differently. One understands that Kotliarevsky did not write a book for his time. He wrote a timeless work. That is why people who live in one or another period can perceive the text completely differently. For example, party leaders emphasized the atheistic content of the work in the Soviet period.”

A LOOK AT THE AENEID FROM THE STANDPOINT OF THE FUTURE

“It is up to us to decide what tool The Aeneid will be in the contemporary history. If we do not find new interpretations, our descendants will. Today, I see a certain crisis in the approach to The Aeneid. We have no right to approach it with banal, glamorous new editions or by making kitsch drawings. Sometimes we become very consumerist and petty about The Aeneid, and this work does not like it. We need to take a look at The Aeneid from the standpoint of the future, not the present.

“We even joked that it would be incredible if Quentin Tarantino made The Aeneid into a movie. Perhaps you need an outside look or something else to get new interpretations. And this can be done not only locally, because The Aeneid was travestied in Germany, Italy, Russia, Ukraine, and Britain in Kotliarevsky’s time. We are part of a worldwide phenomenon.”

Do you plan an exhibition abroad?

“No, I just cannot imagine a way to show our Aeneid abroad, without all other worldwide interpretations of Virgil in art. Of course, were we to show it, this would have to be done with European works of the 18th and 19th centuries.

“Kotliarevsky’s Aeneid is a major part of our heritage. Unlike other travesties that have long sunk into oblivion, it contains a code that is very important for us. However, we still need to understand what part of it is important for the world, to think in the terms of glocalization.”