For starters, in order to create at least a semblance of a polemic I will stress a single point on which I could argue with Prof. Aheyeva. This is in fact a trifle, perhaps even a personal thing. Therefore, I should stress it from the outset not to go back to it again. I regard neither Ulas Samchuk nor Ivan Bahriany as dull or uninteresting authors. Meanwhile, considering the peculiarities of the understanding of literature by adolescents, I think these two authors — on a par with Viktor Domontovych and Yury Kosach — deserve to be required reading in school curricula.

However, this is in fact a minor thing. Meanwhile, problems addressed by Prof. Aheyeva are really pressing and of greater scope. I will try to make a few additions that I hope will be in the manner of decisions, albeit a bit more radical. This radicalism is not a figment of my imagination, either. It is the product of contemplation of the destiny of Ukrainian literature, since its destiny is — whether you like it or not — determined by the way that same literature is presented to and instilled in humans at a tender age.

By this I have in mind the reception and understanding of writers and their works by the individual who will probably never see a living writer (except maybe on television) and will form an opinion of these creatures staring at them from black-and-white portraits in textbooks and readers to which the more daring students add exaggerated ears and moustaches, horns and vampire fangs. These flat and two-dimensional (after all they are on paper) fellows, bearded or shaven, are often the subjects of student rhymes — “It’s easier to chew bricks than learn Tychyna” (it does rhyme in Ukrainian — Ed.) — and this about the subtlest and gentlest Ukrainian poet of the past century. How far should one distance literature from real life and being humane for such a thing to be said? However, not only literature as a school subject is out of contact with reality. Incidentally, do The Day’s readers often recall in their daily lives the valence of copper, solve logarithmic equations, or conjugate French verbs? Meanwhile, school teaches all of these things. But let us return to literature.

Vira Aheyeva has quite correctly worded the question forming the title of her polemic: “An Intellectual Lady or Beauty?”

“Intellectual, of course!” the progressive audience and the average writer alike will call out without thinking where they can get this intellectual stuff from. It has to be raised and cultivated. It seems the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy National University and Prof. Aheyeva personally are doing precisely this, to which we take off our hats to her and her colleagues. But this does not stop me from asking what percentage of their graduates go to work in regional centers of our vast state, meaning not Fastiv or Brovary, but Volnovakha, Tokmak, or Starobilsk, Sarny and Manevychi, Tulchyn and Sniatyn. Since this is where the nation of our state in its twelfth year of independence is being formed. It is precisely there that local and regional departments of education implement school curricula to the fullest extent, including the study of literary works by local authors (these departments are an especially painful subject that we might best leave out of the present discussion). Those implementing the school curricula are largely graduates of local educational institutions, who were taught by the graduates of the same institutions, only older ones. This chain is without end. However, one should try not to break but improve it. In some places the links of noble metal in the form of graduates of Kyiv universities should be added. In other places it should be gilded or silvered by conferring academic degrees on some of the aforementioned seniors. And the teachers themselves as the educators of the future teachers should treat their work with at least a little greater sense of responsibility. They, for one, could abide by the time-honored doctors’ principle of eschewing malfeasance. Our literature is in the same state as all the other social spheres with the adjective Ukrainian attached to them, beginning with filmmaking and theater and ending with philosophy, economy, and politics. To find and emphasize those genuinely interesting works that are really worth reading is perhaps the main order of the day for teachers.

“The Ukrainian literary heritage is not in fact what you are getting at school!” I often feel like shouting out during meetings with young readers. Poorly composed curricula create a distorted picture of literature. And since curricula are composed not in regional centers but elsewhere, those to blame should be sought not in Tulchyn or Volnovakha. I know many worthy and wise people in Kyiv involved in literature and literature studies, and I could provide their telephone numbers, should this proposal be of any interest to the Ministry of Education. However, it does not seem too overwhelmed with the problem of teaching Ukrainian literature. At least not more than with the problems of teaching other subjects and disciplines.

Prof. Aheyeva reflected somewhat overly calmly, “Even this year students claimed that Standard Bearers is still required reading in some schools. I understand that teachers are not paid enough and they don’t feel like reading new books...” At these words I, as a writer, felt anger deep within. Imagine a bus or truck driver who “doesn’t feel like reading” and memorizing new traffic regulations. Imagine a doctor too lethargic to find out about new medications, who is still using iodine and aspirin to treat all diseases. I cannot imagine anyone willing to enlist the services of such specialists. Could this be why “teachers are underpaid?”

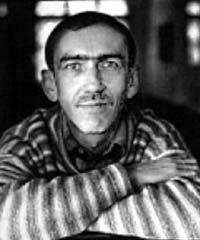

Finally, I could not help noticing the mention of my name and the poem Love Oklahoma in Ms. Aheyeva’s article. A writer is flattered when a person of progressive views, who Prof. Aheyeva undoubtedly is, proposes — even if in jest — including his work in the school curriculum. However, our school system is antediluvian and still uses the carrot and stick model, except that now the twelve-point grading system has replaced the old five-point one. And I would hate to see even one young person punished by an elder for not having read or memorized a poem by Oleksandr Irvanets. After all, punishment results in enmity and antipathy. And I do not want, I fear, the unfounded enmity of an unknown boy or girl toward me personally or all of Ukrainian literature. Thus, I do not want to see my works included into the secondary school curricula.