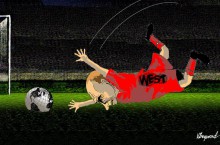

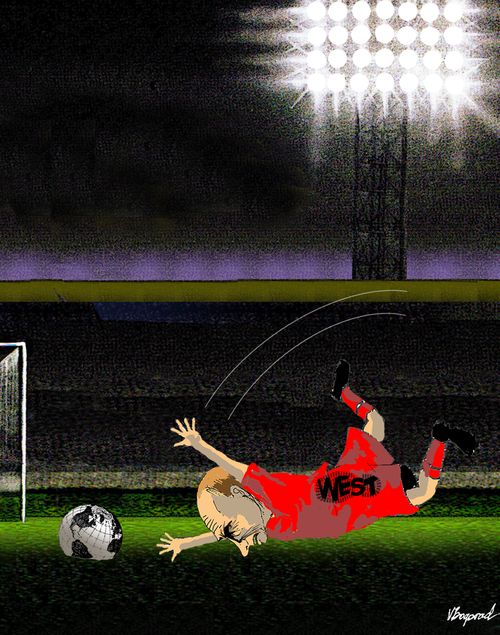

While the world is watching the World Cup in Russia, Ukrainian political prisoners are still on a hunger strike in its brutal prisons. The New York Times wrote in a recent editorial that the Ukrainian film director Oleh Sentsov deserved the full support of the international community.

“In the midst of hosting the World Cup soccer extravaganza, the last thing Vladimir Putin wants to be reminded of is human rights, Crimea or Ukraine. That is a good reason to raise the case of Oleh Sentsov, a Ukrainian filmmaker who has been on a hunger strike for more than a month in a remote Siberian penal colony, to remind the Russian president that his costly sport show does not wipe away his government’s crimes. Following in the best tradition of the Soviet era, Mr. Sentsov was sentenced to 20 years in prison on evidence given by him and witnesses under torture,” the article reads.

“The Kremlin, as always, denies everything... Kremlin-allied media have claimed that Western protests are a ploy to undermine Russia’s World Cup tournament,” the publication says. “No, no and no. Mr. Putin’s regime alone is responsible for the assaults on Ukraine, for Mr. Sentsov’s torture and phony trial. Mr. Sentsov is risking his life to draw attention to Russia’s actions. He and the truth he proclaims deserve the full support of the West, no matter what is going on in Russia’s stadiums.”

A Soviet-era political prisoner who now serves as an MP, one of the leaders of the Crimean Tatar people Mustafa Dzhemilev emphasizes that “holding some international olympiads, festivals, championships, and international conferences on the territory of that country are not steps in the right direction.” At the same time, he says that the current sanctions against Russia would still lead to a “large-scale disruption of its economy.” The details can be found in Dzhemilev’s interview for The Day newspaper.

Now four Ukrainian political prisoners are already on a hunger strike in Russian prisons, and about 70 of our people are held in the dungeons of the Kremlin in total, half of them Crimean Tatars. As a Soviet-era political prisoner who was on a hunger strike for 303 days, longer than anyone else, what would you advise our prisoners today? And in general, how effective is the hunger strike as a method, can it influence the current political regime in Russia? In your opinion, what can change the situation?

“Prisoner hunger strikes often occur in countries whose regimes do not differ much from the Soviet one. That is, in those countries where human rights are brazenly violated. In prisons, hunger strikes are declared primarily to protest against manifestly unlawful sentences, but are often declared as well to protest against gross violations of internal regulations. These include warders abusing prisoners, disgusting and inedible food, excessively cold cells, bath being delayed for a long time, etc. The hunger strike is believed to be a measure of last resort to protect one’s rights, but demonstrative vein cutting is frequent as well. During my time behind the bars, there were even cases of prisoners cutting their throat or cutting open their stomach, that is, some kind of prison hara-kiri.

“But political hunger strikes, that is, ones launched to achieve some goals not for themselves, but for the country, the community, one’s co-religionists or like-minded people, belong to a special category. As for the likelihood of hunger-strikers’ demands being met, there is no definite answer to that question. It is demands that have to do with living conditions that are sometimes met, not political ones. However, people who go on political hunger strikes do not expect to get their demands met, they just want to contribute to the common cause. And in this regard, they certainly achieve their goal. To advise hunger-strikers to stop their protest on the grounds that it undermines their health and threatens their lives is useless, since they know this very well. Those enjoying freedom would do better to take some kind of energetic action in support of prisoners’ demands and call for their immediate release. People usually stop a hunger strike when they see that they have achieved something with their protest.”