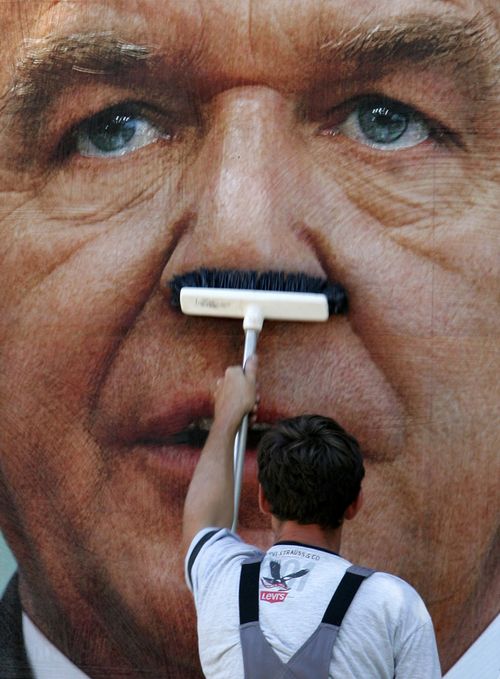

Recently, the world media learned of the new appointment of former German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, who, after his resignation in 2005, had become chairman of the Nord Stream Consortium. This 73-year-old German manager, who has since 2016 actively advocated the construction of the Nord Stream 2 project which threatens Ukraine’s interests as the main gas transit supplier to Europe, has now been appointed as an independent director to the board of the state-controlled oil company Rosneft.

It should be noted that the very name of this former German chancellor was used to coin the name of the phenomenon known as “Schroederization.” It involves Russia spreading corruption in Europe through bribing well-known European politicians, and one of the techniques used is precisely hiring them to work for Russian companies.

So, it is no coincidence that this new appointment has prompted criticism from German politicians and human rights activists. According to the Deutsche Welle, some politicians and human rights activists in the Federal Republic of Germany believe that the former chancellor is promoting Putin’s policy aims for money, while Rosneft is trying to get sanctions against it lifted through Schroeder’s connections.

“He has finally sunk so low as to become Putin’s paid political lackey,” said, in particular, the German Greens’ MEP Reinhard Buetikofer in an interview with the Funke Mediengruppe media outlets which was published on August 13. Buetikofer described Schroeder’s behavior as shameless and urged the Social Democratic Party of Germany to distance itself from its former leader.

REUTERS photo

For his part, Ambassador of Ukraine to Germany Andrii Melnyk called the fact that the Kremlin had been instrumentalizing the figure of the former head of the German government “morally rotten.” The profits of Rosneft finance “a bloody war against Ukraine,” the Ukrainian ambassador emphasized.

COMMENTARIES

Edward LUCAS, senior vice president of the Center for European Policy Analysis:

“It’s disgraceful – both that he did it, and that the European political establishment is not angry about it. This is not only a geopolitical issue – it also affects the health of our democracies. What signal does it send to other politicians nearing the end of their careers if Mr. Schroeder behaves like this and gets away with it?”

Andre HAERTEL, International Relations Department, Institute of Political Science, Friedrich Schiller University Jena:

“No surprise to me. Many German politicians do change after their active mandate-based career into corporate business (see former minister Matthias Wissmann as head of German Association of Automobile Industry). This is not to speak of the ones who hold positions in supervisory boards especially of partly state-owned companies even during their active political careers (see e.g. current prime minister of Lower Saxony and VW). If you consider that the German political system consists of three rather autonomous levels (federal, state, communal), the inter-connectedness of big business and politics is especially high in our country. Germans have a rather uncritical attitude to that in general: if they criticize it it’s mostly connected to individual conflict of interest considerations, not system-wide.

“You need to see that for many Germans the primacy of economics over politics is something they learned (especially in the former West Germany of course) by heart for many decades. Under US security umbrella with not much of a political stake for responsibility they created a typical Handelsstaat which first of all looks also on foreign policy from the position of economic interest. So, for many Germans the sanctions-debate is something completely new: to decide whether politics is more important than short-term economic interests.

“The majority view in Germany on the whole situation in Eastern Europe and Russia itself is following: it is not good what is happening, there has to be an answer to annexation and intervention, but dialog on all levels with Russia must continue (most often cited argument by Steinmeier: because no conflict is solvable without Russians). The sanctions have no big support and are seen as something very temporal (as the discussion around new US sanctions show). That Russia is in earnest working to destroy the West (meddling in US elections, hacking) is either not seen as realistic or ignored by the wider public.

“The problem is that Germans are these days much more annoyed by Trump than Putin. That is making it easy for both the radical left and right to push Anti-American sentiments and belittle or negate Putin’s actions completely. But my main argument for this seemingly schizophrenic policy is still historic. Germans see no contradiction between politically necessary sanctions on the one hand and continued good or improved good business ties on the other, due to the deep tradition of the West German Handelsstaat.”

Lilia SHEVTSOVA, a Russian journalist, Moscow:

“The fall of the former German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder already occurred when he agreed to become chairman of the Nord Stream AG’s shareholders committee. Then he became chairman of the Nord Stream 2 AG’s board of directors. Schroeder thus became a symbol of a long-standing trend among the German and European elites, which called for appeasing the Russian system of autocracy, regardless of who served as the symbol of that system. Now, even a decade ago it was possible to believe that the Europeans (especially the Germans) were ready to embrace the Kremlin because of high hopes. Yes, they hoped that this embrace – ‘rapprochement’ – would lead to a ‘renewal’ in Russia. In short, they hoped that the Russian government and the Russian political class would help to change Russia. This was the hope held by the father of Ostpolitik Willy Brandt, a great German Social Democrat and German chancellor, and along with him, the spiritual father of this hope Egon Bahr.

“But the hopes have evaporated over the past decade. And it was Schroeder (with some help from Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and French President Jacques Chirac) who buried both the hope that embracing the Kremlin would lead to it transforming and the feeling that this very hope was a product of altruism. By becoming a highly paid functionary of the Kremlin, Schroeder became a symbol of the demoralization of the European political class. At the same time, he also raised questions about the moral stance of the German Social Democrats.

“However, after the events of 2014 and the annexation of Crimea as well as the bloody tragedy of the Donbas, the German political class, having experienced a shock, reconsidered its former hopes. It was Angela Merkel who became the cementing factor of the European sanctions package against Russia. New winds have also started blowing in the midst of the German Social Democrats. Yes, the latter find it difficult to abandon their historical legacy, but they do try to avoid being accused of appeasing the Kremlin these days. For them, Schroeder is now a moral and ethical problem.

“There is no point by now in trying to determine what prompted Schroeder’s consent to take on a new post – to become a member of the board of directors of Rosneft, Russia’s largest gas and oil giant. Was it money? Apparently so. A hit to the reputation no longer frightens Schroeder. After all, he has already squandered it. The financial arrangement for this new position is very nice as well. For instance, directors of Rosneft were paid 0.5 million dollars each in 2016 in compensation for their mental efforts. Well, why would he refuse the offer?

“Why do Rosneft and Igor Sechin need Schroeder? It is also understandable: they need him as a lobbyist, who should help Rosneft to lift the burdensome sanctions. However, it is unclear how successful Schroeder has been in his current role.

“It is clear that Schroeder’s sinking to a fresh low irritates the German political circles and especially the German Social Democrats. Now, look at what is truly important! Schroeder has launched a loud anti-American campaign lately, thus trying to balance out his closeness to the Kremlin. And this has been a success to some extent! One can readily imagine what the German business figures are saying as well as those political forces that have always been in favor of a dialog with the Kremlin: ‘Yes, of course, the Kremlin, with its aggressiveness and bearish habits, is by no means an ideal partner. Still, we do know the Russians! We worked for decades in Russia and received dividends. Now, Donald Trump, just look at him!’ That is what you should pay attention to. The European elites and European business interests, who are trying to maintain ties with Russia, will now try to ‘balance out’ their position with blatant anti-Americanism.”