Anniversary celebrations are to be held in the village of Kolodiazhne, Volyn oblast, where the great poet (born Larysa Kosach-Kvitka) spent a significant part of her youth; at the Lesia Ukrainka Museum in Lutsk; at the research institute bearing her name, created together with the Institute of Literature; and certainly at the Kyiv Museum of Eminent Figures of Ukrainian Culture, which comprises the Lesia Ukrainka Museum.

Remarkably, the creation of the Lesia Ukrainka Museum in Kyiv was a challenge, just like the poet’s life itself was. In Soviet times only one small room from her former home was allowed to be used as a memorial (the rest was a literary museum). The museum’s policy was to avoid mentioning Lesia Ukrainka’s relatives, as Izydora Kosach-Borysova and her husband were repressed back in the 1920s-1930s. The shroud of mystery, cast by the Soviet regime, was not lifted until the independence of Ukraine. In 1992, Lesia Ukrainka’s memorial home was re-opened; her literary exposition appeared in 1996.

In the 1960s, when the Lesia Ukrainka Museum was opened, the search for her relatives began. There was no one in Ukraine by that time, but two sisters had survived — Oksana, who was living in Prague, and Izydora in the US. In 1943, when both sisters emigrated they left their personal belongings and documents in charge of the Academy of Sciences and the Shevchenko Scientific Society in Lviv.

The poet’s mother, Olena Pchilka, was Ukraine’s first female ethnographer. In the former Soviet Union she was known as a Ukrainian writer, but treated as a “bourgeois nationalist.” Last year, I was lucky to be present at the ceremony of handing over a rarity to the Museum in Lutsk: a tiny white collar, embroidered by Olena Pchilka. Until recently, the collar had been kept at the Lesia Ukrainka Museum in New York, but they decided to hand it over to the Museum in Lutsk in commemoration of the 160th anniversary of Olena Pchilka’s birth.

The collar was brought to Ukraine by the president of the New York museum board, Yaroslav Leshko, and his wife Alla Leshko (both from Volynia, by the way). The ceremony took place at the Institute of Literature in Kyiv, due to a flu epidemic in Volyn oblast. Tamara Skrypka, deputy director of Lesia Ukrainka Research Institute at the Volyn National University, head curator of archive holdings at the New York Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, who had come to Kyiv from Lutsk, then said: “Olena Pchilka’s collar can be seen in a photograph from 1901, and separately, in her portrait. Olena Pchilka’s daughter, Izydora Kosach-Borysova, gave it to the Ukrainian Museum in New York. As it was not on the main display there, we requested that the collar be returned to Ukraine. Sadly, there are very few Kosach family possessions in Ukraine. The family tragically suffered from repression, so we lost 40 percent of Lesia Ukrainka’s family archives.”

This item of Olena Pchilka’s wardrobe is extremely curious. She was an aristocrat, and no mere amateur in ethnography and traditional arts. She always dressed in aristocratic manner: she had graduated from a boarding school for noble ladies in Kyiv. Her epoch was reflected in her attire.

The Kosachs were a big family. Mykhailo, Lesia Ukrainka’s elder brother, graduated from the University of Tartu and taught at the University of Kharkiv. He died young, at 34, breaking his mother’s heart.

Her sister Olha became a medical doctor near Katerynoslav [now Dnipropetrovsk – Ed.], Oksana became an engineer and worked as a translator at the Center for Ukrainian emigration in Prague. Izydora and Mykola were trained as agronomists.

“As we know, Lesia Ukrainka didn’t have children of her own,” says Oksana Kostiantynivska, senior researcher at the Lesia Ukrainka Museum. “But she was very fond of the children of her elder brother Mykhailo and her younger sister Olha. The only family branch [living] on the territory of the former Soviet Union are the children of Mykhailo Kryvyniuk, Olha’s son, who currently reside in Ekaterinburg. Little Mykhailo was his aunt’s pet. All her unused maternal love morphed into a love for her little nephew. His tiny shirt, embroidered by the poet, is on display at the Lesia Ukrainka Museum in Kyiv (a constituent part of the Museum of Eminent Figures of Ukrainian Culture).

“This is the house where the future poet lived after 1899, when her father, a civilian general and former state councilor, was transferred to Kyiv. He settled right next to his old friends, the families of Mykola Lysenko, Mykhailo Starytsky, and Oleksandr Konysky. After the death of Mykhailo Drahomanov his family also settled nearby, on Pankivska Street. Mykhailo Hrushevsky, too, lived not far off. This neighborhood was dubbed ‘Ukrainian Parnassus.’

“In 1929-30 Mykhailo Kryvyniuk, son of Olha Kosach-Kryvyniuk, was indicted on the ‘SVU case’ [Spilka Vyzvolennia Ukrainy – the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine. – Ed.]. He was offered to become an informer. Kryvyniuk realized that he was going to be arrested. The family saw him off as if to prison. Yet no one opened the door at the designated address. It turned out that the investigator himself had been arrested. So he had to run away (no one would get Interpol to look for him).

“He moved to Sverdlovsk [now Ekaterinburg. — Ed.], Russia, and married a doctor (also daughter of a repressed man). The couple had three children. The youngest, Maria, became a biologist and came to Kyiv two years ago together with her son Mykhailo (all the boys in the family are christened either Mykhailo or Vasyl). The young man was in his third year at university at that time. Maria wanted to show him the places where their relatives had lived.

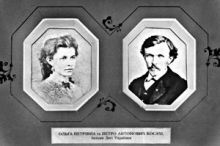

“The grandchildren of Lesia Ukrainka’s sisters Izydora and Oksana first met at the Museum of Eminent Figures of Ukrainian Culture in 2003, when Ukraine marked the 90th anniversary of the poet’s death. The former home of the Kosach family is also on the premises of the Museum. It was the first time that they had seen each other. Olha Petrova-Luton had flown in from America, Roberto Haab had come from Switzerland. I had an opportunity to speak with Lesia Ukrainka’s relatives.

“The poet’s great niece and nephew said that they were able to find each other thanks to the Internet. After his mother’s death, Haab became curious about his Slavic ancestry, and in May, 2001, he was already walking round the rooms of the house on Saksahanskoho Street, where his grandmother Oksana and great-grandmother Olha (aka Olena Pchilka) used to live. He was trying to understand what ‘the great Slavic soul’ was.

“Later, he came to Ukraine several more times, to visit the museum in the capital, peer at the portraits of his relatives, wander about the rooms, look at the furniture, books, things that used to be theirs, and breathe in the air of his second fatherland, which he had discovered so unexpectedly.

“In 2003, he sent an inquiry to find out if there was anyone who knew the Kosach family. His cousin Olha replied from America. She sent him some photographs via e-mail and wrote about their family. This was the start of their correspondence.

“Roberto brought to the Museum the original letters, written to his mother by Izydora. He said that he would like to immerse himself in his ancestors’ atmosphere. When he stood next to his grandmother’s portrait, strange emotions surged in him. He could feel the powerful energy emanating from the portrait.”

Kostiantynivska recounts Haab’s testimony: “Olena Pchilka was an extraordinary woman and a strong personality. I can hear her power, he said, she must have been a woman of character. I believe her soul lives in this house. My great-grandmother wasn’t a revolutionary like my granddad. She was convinced that a revolutionary has no right to marry an ordinary girl. This might be why she disliked my grandfather, although they had always been on good terms.

“My mother came to Ukraine only twice. She didn’t remember her first visit, at the age of two; but the second time she came as an adult tourist. She had no idea about Ukraine, but she had a good command of the language. She read Ukrainian books, and studied the literature.

“Mother was as delicate and frail as all Kosach girls. She was exceptionally beautiful, with pretty hair, gray eyes, and regular features. She graduated from the Prague university and conservatoire. She played the piano. In 1939, mother went to Italy where she met my father, who had come from Switzerland to work there. Both me and my sister were born in Italy, but now Iryna is living in Spain.”

Kostiantynivska also remembers the tale of Lesia’s great niece: “Meanwhile, Olha Petrova-Luton said that in the States she had often met with Vasyl Kryvyniuk, who would come over from Canada. ‘I am happy to see in the museum the things which I remembered as a child,’ she said. ‘Some of them belonged to Lesia Ukrainka. For instance, the pen, the ribbon, the lace, the necklace of fine glass beads, the kerchief, buttons, and books… Grandma Izydora kept them, and mom (Olha Serhiiv. – Author) handed them over to the museum together with grandma’s things. I am grateful to the staff of the museum, who help preserve the memory of my grandmother Izydora, great-grandmother Olha, and also grandfather Zoria (Svitozar Drahomanov. – Author), as well as my grandmothers Lilia Kryvyniuk and Oksana Shymanovska.’”