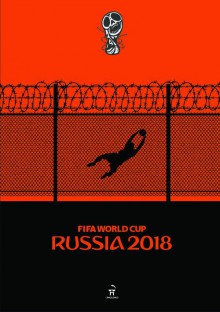

Many in Russia regard the approaching FIFA World Cup as a disaster. With reason as the Russian authorities have decided to do even better than their Soviet predecessors who ordered Moscow, Kyiv, Leningrad and other cities that hosted the 1980 Summer Games purged of all “suspect” and “unwanted” elements. At the time, dissidents, pickpockets and panhandlers, prostitutes (except for those under KGB control, meant to service foreigners), beggars, and persons with a criminal record were expelled from these cities and kept away from them for the summer. It was done so the guests from abroad could see no “birthmarks” of socialism, considering that Soviet propaganda had been assuring one and all that there was no crime or prostitution in the USSR, and that those few who voiced their opposition to the regime were mental cases.

In June 1977, the 11th Department was attached to the Fifth Directorate of the KGB. It was tasked with “Chekist operations aimed at frustrating subversive enemy actions and [neutralizing] hostile elements during the preparations for, and the holding of, the Summer Games in Moscow.” In fact, after the US, most other Western countries, and a number of Muslim states declared they would boycott the Moscow Olympics because of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Chekists were happy they would have less work to do. Most children who lived in Moscow, where the largest number of foreign guests would gather, were sent to Young Pioneers summer camps lest they meet with foreigners and expose themselves to the West’s pernicious influence, asking for chewing gum and ballpoint pens. Many residents who weren’t dissidents and had no criminal record were advised to spend vacations somewhere away from Moscow. Employers and managers of industrial enterprises and various offices and institutions willingly let them go, following instructions from “upstairs.”

As a result, the population of Moscow was reduced several times for the duration of the Games and the residents of suburbs had a hard time getting to town as the number of commuter buses and trains was also reduced. This and imported foodstuffs supplied to the retail network (some of them never seen or tasted before and then long after the Games – at the time oil prices were high and the State Treasury kept receiving petrodollars) alleviated the shortage of provisions and long lines in Moscow just before and during the Olympics. The authorities didn’t want the guests from abroad to see any of this, lest they call in question the well-being of the Soviet people living under a planned socialist economy. Moscow residents would fondly refer to the Games as “our yummy lie.”

Today, preparing for the FIFA World Cup, the Russian authorities have apparently borrowed much from their Soviet counterparts’ experience. For example, high school students in Moscow and other host cities will be encouraged to spend the period in summer camps, away from town. Those who stay will have a fifth school term to keep them off the street. This time it is not to protect them against the West’s pernicious influence, but for fear that the anti-government opposition will try to stage anti-Putin rallies in Moscow and other host cities during the tournament. These rallies are known to have actively involved college and senior high school students in the past.

Security arrangements are unprecedented even compared with Soviet times. So many threats, indeed! Russian and foreign soccer fans (especially guests from the UK). The Russian police and FSB brass must be rubbing their hands, smiling over the fact that the Italian national team couldn’t make it, so there will be no savage tifosi. However, there are other problems, considering that Russia has many serious issues with the rest of the world. There are likely to be protest rallies against Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and Syria, demanding that Oleh Sentsov, currently on termless hunger strike, and other Ukrainian prisoners of the Kremlin be released, pickets condemning the Kremlin’s support of Assad, the poisoning of the Skripals, persecution of LGBT people, restrictions on political rights and freedoms, you name it. Also, ISIS and Al Qaeda terrorists may well penetrate Moscow under the guise of soccer fans. Russian labor unions are threatening rallies of protest against the State Duma’s bill to prolong pension age.

In view of this, harsh restrictions have been imposed on all rallies and demonstrations. They will remain in effect from the beginning of June until the World Cup’s visitors leave the Russian capital. One-man pickets are actually banned, each requiring government approval like all mass pickets and rallies. This has never been practiced and obviously runs counter to the law, but law has long lost its meaning for the Russian authorities. Formally, this authorization is something like event activity coordination, but the fact remains that such events have long been banned in downtown Moscow. At best, they are allowed in the outskirts. It will be also there that soccer fans will be allowed to gather and enjoy themselves. The idea of turning part of the Moscow University campus in Lenin Hills into a fan zone leaves most university students and lecturers anything but happy. They are afraid that fans will damage the environment, historic sites, and university facilities. Also, a number of students will have to finish the academic year ahead of schedule and leave their dorms to make room for security forces that will be brought to Moscow.

Several students have been arrested by the police while taking exams, on charges of “vandalism” – after leaving the inscription “No To Fan Zone!” in red on an advertising table. The damage is assessed at 65,000 rubles (sic). And this is just the beginning. There is no telling what will happen toward the end of the tournament when passions will be at a boiling point.

Boris Sokolov is a Moscow-based professor