As a kid I loved books about American Indians because these people were so very much like our Zaporozhian Cossacks with their love for freedom, mental sharpness, inbred understanding of nature, and even their unmatched skill of giving each other accurate sobriquets. Remarkably, decades later, leafing through James Mace’s posthumously published book, I discovered that there had lived an American Indian who took the tragic history of my people as close to heart as I once did his people’s. True, my perception of American Indians remained in the sphere of childish emotions, however positive, whereas his attitude to Ukrainians was expressed in research papers and newspaper articles that help us become aware of ourselves as a nation despite the past genocide.

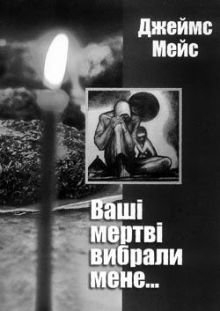

In fact, I started reading Your Dead Chose Me with Natalia Dziubenko-Mace’s refined afterword. I was right because she wrote about that “bit of his legacy” with such love that I immediately felt like reading the rest of the book.

Your Dead Chose Me is a textbook on patriotism and heartfelt attitude to national history, intended for all Ukrainians who are conscious of their national identity, and especially for those who are not. It is an example of the summits of human spirit that one can ascend to when approaching a task professionally, with a sense of responsibility, and with all of one’s heart.

Dziubenko-Mace wrote bitterly in her afterword that James’s work met with dead silence on the part of scholars in the West and Ukraine. While I agreed with her, I constantly found myself thinking that many of Mace’s conclusions (especially with regard to the 1932–33 Holodomor) have recently been voiced, using his formulations, at the highest political level, made known to Ukrainian public and international community, reflected in literary works, films, monumental art, exhibits, museums, and the irreversible process of declassification of archival documents.

By way of example, there are letters in a criminal case file stored in the archives of the Kirovohrad regional SBU directorate, dating back to 1933. A serviceman by the name of Vasyl Dzina was then sentenced to three years of corrective labor on charges of anti-Soviet agitation. Son of a farmer, he courageously told the interrogator that he had begun voicing dissent after receiving letters from his relatives in Bosky, a village in Dobrovelychkivka raion, Kirovohrad oblast.

To quote from the file, “My brother Ivan wrote that his child had died, and my sister Maria wrote that life in the collective farm was hard, she was living in misery and hunger, and this was true of all collective farmers… She informed me that Ivan K., resident of the village of Yuriivka, stabbed a woman to death after she asked him to allow her to spend the night at his place. After that he ate her… he made sausages from her flesh… My other sister Tetiana asked me to put a slice of bread in an envelope and mail it to her, so she could at least see what bread was like, because there was no bread in the collective farm. All these letters have made such an impression on me that I decided that all collective farmers are starving… While still at home, before being drafted into the Red Army of Workers and Peasants, I saw people eat fallen horses on more than one occasion…”

The case file also contains a letter from Vasyl Dzina’s sister Maria, dated June 20, 1933. It reads: “Vasyl, I am down with malaria… you should see me now, I’ve lost so much weight. You know Vasyl, I am sick, yet there is nothing to eat except rye from our vegetable garden. We harvest it once it starts getting yellow. The head of the artel does as he pleases. Sashko talked to him and asked him to give him some milk for me because I hadn’t eaten all day. The man replied, ‘So let her die…’”

Finally, an excerpt from Tetiana’s letter of April 24, 1933: “Vasyl, I was engaged… but then I refused to marry the man. We held family counsel and decided against my marriage, what with the famine and all. You know, when you are hungry, you are not interested in anything. It’s horrible to watch a man walk down the street and then drop dead. Other people step over the body and it lies there for three days until it is buried. Vasyl, they bury six or seven bodies in one grave every day. Remember that year when lots of horses died? That’s what’s happening to people this year. Vasyl, if only you saw people dig in the steppe with spades and drop dead right there, beside their spades…”

Regrettably, Mace is right when he says that those who don’t want to believe that this really happened will never believe it, and no facts or documents will convince them otherwise.

The good thing is that the multivolume publication entitled “The National Book of Memory of the 1932–33 Holodomor Victims in Ukraine” (specifying such victims in every oblast) finally appeared in print, after Mace’s death. It contains endless lists of names that each of us must remember about them. A great deal of credit for this project is due Mace.

To paraphrase him, our dead chose him, of all people, not only to tell the rest of the world the truth about the Holodomor as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people. Mace wrote that the problems faced by Ukraine today are problems of a country that retains the psychological and physical scars of genocide, not only in people who survived the terrible evil of Stalinism, but in the entire nation, which was crippled so much that when it attained independence, the only available structures of power were the ones formed during the post-Stalinist period. People manning these structures were appointed by people who were simultaneously products and victims of this system. In other words, Mace prompted his readers to perceive Ukraine as a postgenocidal society. He explained why Ukrainians are an ethnic minority in their own country.

Let us hope that from now on there will be no silence in response to his invitation to discuss this issue. There simply can be no such silence. Indeed, he survived and even turned into a certain permanent detail on the Ukrainian intellectual stage.

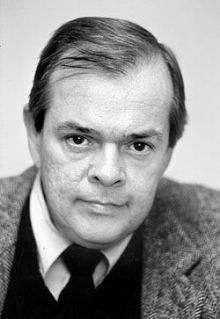

Naturally, those who know nothing about James Mace and who haven’t read his articles in Den’/The Day should start with “Autobiography” at the beginning of this book. Remarkably, it does not just lists dates and events but offers a story about one’s personal intellectual quest. It helps the reader understand how an ordinary provincial young American fellow did more than develop an interest in Ukraine (regrettably, there are many people in the world who do not know that this country exists), how he eventually became its luminary — and there is no overstatement here! How he proceeded from the understanding of the path of tears of his Cherokee tribe to the understanding, on a profoundly human and emotional level, of a tragedy suffered by the faraway Ukrainian people.

The first learned guide on this path was the University of Michigan lecturer Roman Szporluk who instilled in his student a lasting interest in Ukraine and the language. (I know from my experience at Dnipropetrovsk University that, back in the 1970s, both US and Soviet students were keenly interested in early Soviet historiography. Mace writes that in the 1920s historians could look for answers and discuss problems.) Interestingly, the first book young Mace read in Ukrainian was Panas Fedenko’s Ukrainsky rukh XX stolittia (Ukrainian Movement of the 20th Century).

In his autobiography and other works Mace refutes communist propaganda’s habitual allegation that scholars in the West constantly thought of ways to fuel the fire of the concept of man-made famine in the early 1930s in Ukraine. In actuality, it was the other way around. Scholars in the West treated Mace’s conclusions warily, with caution, even with undisguised hostility. They believed that all things Ukrainian were somehow blemished. Suffice it to mention a book that refuted the results of Mace’s herculean work, [Douglas Tottle’s] Fraud, Famine and Fascism — The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard. How was it possible to break through that wall of incomprehension? Why was it built and by whom? Detailed, emotional answers to these questions are found in numerous works included in this publication.

Mace insisted that Ukrainians must rebuild and return all that which they lost, even at the cost of tremendous efforts and time. I recommend reading his “A Tale of Two Journalists: Walter Duranty, Gareth Jones, and the Pulitzer Prize,” which tells a story about how this prize was conferred upon an unworthy individual. It reads: “By the early spring of 1933, the fact that famine was raging in Ukraine and the Kuban, where two-thirds of the population were ethnic Ukrainians, was common knowledge in Moscow among foreign diplomats, foreign correspondents, and even the man in the street… The whole story of denying the crimes of a regime that cost millions of lives is one of the saddest in the history of the American free press, just as the Holodomor is certainly the saddest page in the history of a nation, whose appearance on the world stage was so unexpected that there is, in fact, a quite successful book in English, The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation.”

This unusual [native] American who lived in and worked for Ukraine constantly felt that he had not done something that had to be done at all costs. Truly, this is an example to be followed. As it is, our history is still being written by Beauplans and Alepskys. The good thing is that such rare foreigners (among them James Mace, of course) understand our problems and tell the rest of the world how good Ukrainians are and how much humankind needs them.

Mace wrote that he was stunned to realize that Ukraine had suffered a tragedy of biblical dimensions. He gave a detailed account of the political and other reasons behind the Holodomor in Ukraine. He explained that he wanted to “atone, if only partially, the huge guilt of Western science before Ukrainian scholars and the guilt of the American people before the Ukrainian people. Time has come to say out loud that Western science was at fault regarding Ukraine.”

He addressed the Ukrainian diaspora and made a paradoxical statement: “The Ukrainian cause has died. Instead there is a living Ukraine where countless problems have to be solved… Ukraine is a country and nation faced with big problems that must be solved.”

It should be noted that Mace’s works are written in an aphoristic style, using apt expressions like ”everything is possible in Ukraine,” “knowledge deserves celebration,” “one of the aims of knowledge is to cure,” “history is like disinterment,” “rifts are a major phenomenon of the Ukrainian political movement,” “if you lack arguments to refute a certain concept, you ridicule it,” “Ukraine is a rich country; it’s just that its people are poor,” “Ukraine can’t be saved from Ukrainians” (regarding the 1999 elections), “education is the only thing no one will ever be able to take away from you,” and so on.

He boldly introduced words that he thought did not have Ukrainian equivalents but aptly described certain Ukrainian realities — for example, malapropism, an extremely topical concept for Ukraine today. I wonder if Gongadzegate, which is still being widely used, was Mace’s coinage.

His articles, written in 1993–2004, have not lost their topicality. They may have even gained some. He wrote that a lot is being said in Ukraine about the heavy totalitarian legacy and genocide, but very little is being done to secure Ukraine’s happier future. He was and is still right. He asks how come the very existence of independent Ukraine turned into a disputable matter even in Ukraine. He answers himself: genocide.

There didn’t seem to exist a single topical issue to which Mace wouldn’t quickly respond, including the national elite, women’s problems, “the Valuyev syndrome,” “cleptocracy,” Chornobyl, Crimean Tatars, investment climate, and civil society.

Mace elaborated on Volodymyr Vynnychenko’s idea that Russian democracy ends where the Ukrainian issue begins. He came up with a brilliant work entitled “Lenin without Ukraine or Dmitrii Volkogonov as a Mirror of Russian Democracy.” It is interesting not only for professional historians and political scientists (who found quite a few new facts in it). Mace sums it up: “There was no Lenin without Ukraine, but may there be Ukraine without Lenin! For Ukraine Leninism has been and will always remain an expansion of the Great Russian idea. If Ukraine and Russia reach an understanding, it will be only by revealing the whole truth about Lenin and Ukraine, not by sharing parts of it as is the case with Volkogonov.”

Mace had a strong sense of responsibility. He was one of those who regarded history as an exact science. “When you write about something, you are responsible for the content,” he explained, so it’s best to limit yourself to what you actually know.” “For a historian, accuracy is not a virtue but responsibility,” he added.

He may have been prophetic in certain respects. Long before the recent gas rows with Russia that affected all of Europe, he wrote that one ought to feel especially concerned about the leasing out of the Soyuz pipeline to Russia’s Gazprom because energy resources would quickly become the essence of 21st-century geopolitics.

Mace stressed he was not a writer or critic, just a trained historian, an analyst of political realities, a teacher by vocation (he loved lecturing at Kyiv Mohyla Academy), and journalist due to circumstances. However, there is nothing coincidental about his creative work being discussed by an Internet literary periodical, not only because he was actually an erudite versed in the world classical literature (Shakespeare, Poe, Mark Twain, George Orwell, etc.) and knowledgeable about the Ukrainian literary process ranging from Taras Shevchenko to the poetic group Bu-ba-bu.

In his works one finds as much — if not more — concern about the status of the Ukrainian language than in those of many current litt rateurs and statesmen tasked with protecting this language. He wrote that lack of respect for the native language and culture, while constantly flirting with someone more powerful and richer, be it Russians or representatives of some miniature foundations in America, is the burdensome and sad legacy of the past. No one has anything against Russian culture or language, but for as long as Ukrainians themselves regard their language as second rate, this nation will remain divided.

He was concerned about the fact that so few people bought books in Ukrainian and used Ukrainian in their daily life and that Ukraine’s information space was even weaker than under the Soviets. As a foreigner, he raised the acutest matters in a most delicate manner. He stressed that no one except Ukrainians can decide which language to use in speaking and writing and that although he was now living outside the United States, he remained American.

This book contains quite a few original ideas about people who represented the “Executed Renaissance.” He believed that mass terror against Ukrainian culture was the indisputable proof of the Kremlin’s intention of annihilating Ukrainian national identity. One could read Bulgakov, but an entire generation of Ukrainian men of letters, who were not inferior to the Russian “Silver Age” representatives, had been wiped out, including Khvyliovy, Yanovsky, young Sosiura and Tychyna, and Zerov.

Every effort had been made to destroy the national roots of Ukrainian culture and language as the intellectual cornerstone in the cultural development of any society. What was left did not suffice to become a member of the international community of nations. Not surprisingly, it was during the Holodomor that Stalin sent directives to immediately stop Ukrainization everywhere. Ukraine’s national renaissance was choked with its own blood. Who knows how many Shakespeares, Goethes, Tolstoys, Dostoevskys, Dvo ks, or Mickiewiczes the Ukrainian land could have produced but for the crimes committed during the Stalinist period, James bitterly asked.

The book contains apt references to Ivan Drach, Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Oles Honchar (who read Harvard’s three-volume collection of Holodomor eyewitness accounts as if it were “Black Iliad,” and Mace was embittered by pokes taken at him), and Volodymyr Maniak. Mace wrote heartfelt obituaries on Solomia Pavlychko, R. Andriyashyk (the first one to have written the truth about OUN-UPA), and Petro Yatsyk. Mace had his favorites among the contemporary Ukrainian men of letters, specifically Oleksandr Irvanets (he said he was one of the wittiest individuals involved in the current Ukrainian literary process), while referring to himself as a friend of many noted contemporary Ukrainian authors, both living and dead. He even commented on Buzyna’s ravings, saying that if you write about Adam Mickiewicz as a turncoat in Poland, someone is likely to try and punch you in the face.

Finally, he said: “I was not born Ukrainian but the Ukrainian people seems to have accepted me. Together with it, I have tried to make a contribution to Ukrainian national culture, via it — to world culture, and through it — to the overall heritage of humankind.”

( The Day’s Library Book Series).

Kyiv: Ukrainian Press Group, 2008.