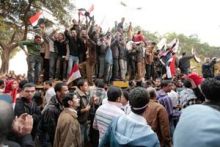

After the tumultuous riots the situation in Egypt is slowly settling down. Tahrir Square is emptying, volunteers are removing litter and professional protesters from it. As one activist said: “It’s a pity everything is over now. I liked staying here all the time.”

Currently a lot is being said about the country’s democratic road ahead after a long period of authoritarian rule. Riots in Cairo and other cities finally deposed the long-reigning despot. Yet the massive demonstrations were a kind of background against a confrontation within the country’s elite. Then there is the very important, in case of Egypt just as in Tunisia, foreign factor. It was this factor, most likely, that tipped the balance for Mubarak’s resignation in the last moment.

It was not the “export” of protests from Tunisia but an exacerbation of contradictions in the ruling elite that was behind the events in Egypt. One can call the opposing groups “the military representatives” and “the party representatives.”

The latter elite group includes not only the leaders and highest functionaries of the ruling National Democratic Party, but above all representatives of Mubarak’s “family” in a broad sense of the word, and the part of the elite that was formed under the former Pre-sident Anwar El Sadat. It is obvious that the party representatives had a vital interest in the stabilization of the situation and prevented Mubarak’s resignation in all possible ways. This group’s influence shouldn’t be underestimated. Especially taking into account its close international connections and control over the most important spheres of the economy. This explains the procrastination in the process of removing Mubarak from power.

In their turn, the military representatives, first of all the army, were gradually moving toward the sacrifice of Mubarak to retain the foundations of the regime. That explains the maneuvering of the ge-nerals who, in fact, dissociated themselves from dispersing the demonstrations. It was rather easy for them to do it because in Egypt, as well as in Israel, their is a deep respect for the army. Taking into account the future, the generals thought it was rather dangerous to cause a clash between the army and people in the streets and squares. At the same time, the generals didn’t want to dethrone the president, since this would automatically make the future regime illegitimate, regardless of how many Egyptians would support this. It would be rather problematic for them to gain further international recognition, and the military understood how important it is. The country lost billions of dollars du-ring the protests — the tourism business, which brought in big profits and employed thousands of people, is closed and it will take a considerable amount of time and money to bring it back up to speed.

And one more factor. It was very important for the military not to make a precedent of dethroning a leader, since it could considerably undermine the regime’s internal stability. These are not empty words for Egypt. After all, Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power as a result of a coup in 1952, as a leader of the underground organization of Free Officers. They could remove Mubarak even against his will but it was essential to do it without blood and observing the appearance of decency. And perhaps with guarantees for the future, including ones regarding the “honestly earned” capital. In addition, Mubarak is not a stranger for the army. A former pilot, a hero of the war against Israel of 1973 — the generals could not ignore this, gi-ven the army’s specific mentality.

The party representatives had a weaker position from the very beginning and therefore, after a number of maneuvers, the military managed to force the leadership of the National Democratic Party to resign and gradually push Mubarak to his abdication. How-ever, on Friday, February 11, when the entire world was waiting for him to do it, he refrained once again. Then the military lost its temper and again used the argument of Tahrir Square. Perhaps this cat-and-mouse game could continue for some more time, but Mubarak was pressed on from abroad.

Certainly, both Washington and European capitals were thinking first of all about saving Mubarak’s regime without Mubarak. Oil prices started to increase and problems with tankers passing through the Suez Canal aggravated the situation even more. Ensuring regular oil and gas supply through pipelines passing through the Sinai Peninsula become problematic. What worried European leaders even more was that food supplies would not be able to get through the Suez Canal. The route around Africa makes delivery periods eight days longer to the US and 23-25 days longer to Europe. The impact on prices is obvious.

One should mention one more problem of the slightly frightened West. The course of the confrontation, as one could predict (and this was completely proved), would inevitably make Tahrir Square even more radical. And the Islamic slogans, which were not very popular initially, could gain enough supporters. Not by accident did the Iranian clerical leadership, right after the beginning of the events in Egypt, hurry to call them a result of the influence of the ideas of the Islamic revolution of 1979. Thus, Iran’s government’s policy of “exporting the Islamic revolution,” which was already realized in Lebanon and Iraq, has once again resurfaced. On Friday, February 4, during a prayer in Tehran’s central mosque, the religious leader ayatollah Ali Khamenei addressed the people of Egypt in Arabic: “Until this idea (of the Islamic revolution – Author) becomes reality, don’t cease your struggle, don’t surrender to Mubarak’s regime. The country’s religious activists must show the people an example of serving patriotic ideals.” In a few days, on February 8, Khamenei again connected events in Egypt with the influence of the Islamic revolution. The specter of fundamentalist Islamizaiton (or Iranization) of Egypt actually became an idee fixe for Ukrainian politicians and experts as well. It was widely discussed during Savik Shuster’s and Yevgeny Kiselev’s talk shows.

Perhaps they removed Mubarak in time. The main struggle between the politicians and the military will now be not for the president’s post (the Muslim Brotherhood and ElBaradei, a leading opposition fi-gure, already declared they would not stand), but for the posts in the government. From all appearances, Omar Suleiman will become the only and invincible future president of Egypt, which is convenient for many in Egypt, the West and Israel. However, it remains to be seen how the relations between the military, the civilians, and other politicians will play out. So far one can say rather definitely that in the near future Egypt’s foreign policy course will not change.