The National Bank and the government have begun to change their approach to the task of inflation control in Ukraine. The signal for this was the abolition on April 1 of the law requiring all exporters to sell 50% of their foreign currency revenues (in effect for more than 6 years). This decision was made to decrease the emission that the National Bank uses to buy foreign currency flowing into Ukraine. Since emission directly affects inflation, a decrease of the former has to lead to a decrease of the latter. The swift strengthening (revaluation) of the hryvnia against the dollar comes as a side effect. According to the prognosis made by the Ministry of Economics, by the end of the year the rate of exchange will be close to 5-5.1 hrn/$1 (revaluation by 4-6%).

At the same time, the need to boost inflation control is caused by at least two factors. First is the continual increase since last fall in prices for essential commodities. Second is the approval of the new budget for 2005, which is almost as socially-oriented as it is inflationary. The parameters of the new budget were calculated on the basis of nominal GNP for 2004 of 345.9 billion hryvnias, GNP for 2005 of 436 billion hryvnias, and real GNP growth rate of 8.2%, which give us a price growth rate of 16.5%. It should be mentioned that this figure defines inflation in all markets, not just the consumer one. If the government is planning an official figure of consumer price growth of 9.8%, then manufacturers’ prices will increase by more than 17% (whereas the official planned figure was 12.9%).

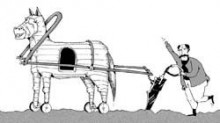

These figures aren’t the most optimistic. However, if we look at inflation as a component with more general contours of the government’s economic policy, we may draw some interesting conclusions. It seems that the government is going to abolish the export-oriented economic development model. The first evidence of this is the neglect of exporters’ interests. It becomes apparent from the intention to allow the national currency to revaluate, from the uncertain situation with privatization, and from the budget law that strengthens taxation and eliminates free economic zones. Further evidence is the social reorientation of the government’s policy, as shown by the abrupt growth of social payments from the budget and the lowering of import customs duties to make imported goods cheaper. The fact is that development at the expense of stimulating domestic demand is incompatible with the export-oriented model because the latter presupposes low wages and foreign markets for production.

Virtually all the measures that annoy exporters are unpopular: the average Ukrainian will hardly rejoice over the depreciation of their dollar savings, while businessmen will not be happy with tax increases and investment risks. However, these measures might be sufficient to “cut off” the inflation wave that started last September because of pension emission and which was developed under the present government. Monetarists think that the time lag between emission and the concomitant price growth is 7-8 months, which is why inflation caused by September’s increase in social payments will peak in April and May. The unpopular measures adopted today should help to bring down this inflationary splash. After this, let us hope that the government shows a sense of proportion and does not make any sudden and contradictory decisions. In other words, difficult post-revolutionary steps were objectively necessary to start the transformation of the economic system, but the new Ukrainian government will soon have to strictly limit such measures to retain the domestic and foreign credit of confidence.

At the same time, shoring up the national currency will not merely ease inflation. It will lead to a growth slowdown of the National Bank’s gold and foreign currency reserves, the lowering of the nominal deposit and credit rate and speed of the economy’s remonetization, and more flexible exchange rate formation in general.

This year, the National Bank obviously decided to completely deprive the economy of the monetary component of inflation. According to the above GNP values, the hryvnia exchange rate, and the expected increase in the National Bank’s gold and foreign currency reserves for 2005 by $4.1 billion, the level of the economy’s monetization will remain virtually unchanged during the year, having stopped at the comparatively low figure of 36%. Until next year the monetary policy will perform a restrictive and stabilizing role of a counterweight to the government’s social and inflationary policy, but by no means an incentive role. However, this may be useful for avoiding a rapid decrease of the economy’s growth rate as a result of overheating and “socialization”: at work here is the principle “slowly but surely.” The direct use of the stimulating function of a monetary-credit policy will begin after the parliamentary elections. In the future, the current level of monetization will once again allow the use of the emission mechanism to stimulate growth on a relatively non-inflationary basis because emission will be absorbed by businesses’ demand for circulating assets.

The Ukrainian government’s switch from foreign to domestic loans should be mentioned here. This year it is planned to obtain credit in Ukraine to the tune of 6.2 billion hryvnias and to repay 3.1 billion, while for foreign loans these figures are 3.2 and 6.2 billion hryvnias, respectively. It is clear that the debt policy indirectly affects the inflation process because government loans in the domestic market sterilize the monetary aggregate. However, it is still not clear whether the government has some other reason for refusing foreign credits in favor of domestic ones, besides manual anti-inflation control.

At present the National Bank could suggest that commercial banks lower hryvnia deposit and credit rates. The paradox lies in the fact that as the nominal rate is lowered, real bank revenues from deposit credits and debits resulting from the strengthening of the hryvnia can be retained. At the same time, since revaluation takes place against the background of inflation (as price increases but not as a devaluation of currency!), the value of credits for businesses would decrease. In this case, several interesting consequences are possible. For example, deposit and credit rates in the Ukrainian national currency will approach foreign currency rates. Secondly, the National Bank of Ukraine will be able to credit commercial banks more actively (because it will be spending only part of its hryvnia assets to buy surplus currency), and its rate will become not just a signal but in fact an effective tool of monetary management. Thirdly, this change of approach to monetary management will logically cause a shift from a virtually fixed currency exchange to a floating one (within a certain range), to which experts are already pointing. In point of fact, economically weak countries cannot allow a floating rate of exchange, so this approach would be further confirmation of our country’s real economic growth.