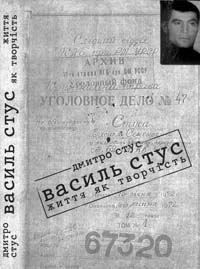

Dmytro Stus’s monograph Vasyl Stus: Zhyttia Iak Tvorchist [Vasyl Stus: Life in Creativity] won the Grand Prix at the 6th Book of the Year nationwide charity drive this past March. Critics are calling it a major event in Ukrainian biographical writing. Published last year with a pressrun of only 1,000 copies, it sold out in two months. The book is based on documents that Dmytro Stus collected all over Ukraine and Russia, and includes his candid and heartfelt memoirs in which the poet and patriot Vasyl Stus is portrayed as a son, husband, and father. We know little, if anything, about this aspect of his life. In the following interview the author went beyond the discussion of his book and touched on present-day Ukrainian reality.

“THREE-FOURTHS OF THE BOOK WAS WRITTEN BY A RESEARCHER AND ONE-FOURTH BY A SON”

“Dmytro, you were the compiler and author of introductory essays to Vasyl Stus’s books of poetry Veselyi Tsvyntar [The Merry Cemetery], Vikna v Pozaprostir [Windows into Beyond-Space], Zolotokosa Krasunia [The Golden-Braided Beauty], Lysty do Syna [Letters to a Son], and Palimpsest. Together with Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska you headed a team of authors who collected and prepared a six-volume collection of the poet’s works for publication. What made you write your father’s biography?”

“In the early 1990s there was no one to research Vasyl Stus’s literary heritage. The people who were interested in or who knew the real Stus and wrote about him were mostly relatives and friends. They did this with almost no support from the state, even to this day. Most of the credit goes to Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Vasyl Ovsiyenko, Kostyk Moskalets, Oksana Dvorko, the actress Halyna Stefanova, who wrote the one-man-play Palimpsest, and the bard Serhiy Moroz, who was the first to compose music for Vasyl Stus’s poems. All of them were fascinated by this personality, who developed his own concept of life and left a heritage of matchless poetical works. We matured while we were working with these materials, which turned out to be super rewarding.

“I constantly asked myself why I was doing this. After all, work on father’s collections was not financially rewarding. On the contrary, I had to invest money earned elsewhere and occasionally got myself into trouble. But somewhere deep in my heart I always knew that this material was enriching my personality.

“Mykola Zhulynsky spent a long time convincing me to write Vasyl Stus’s biography. I resisted for a long time. Finally, when I got into a conflict with my immediate supervisor at the Taras Shevchenko Institute of Literature of the Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences, I decided to quit. But Mykola Zhulynsky, who directs this institute, reminded me about the monograph and advised me not to leave. Persuasions and refusals lasted until I began my doctoral studies. The book Vasyl Stus: Life in Creativity is the result of my three years of doctoral studies, during which time I studied documents at the archives of the Security Service of Ukraine and traveled throughout Ukraine and Russia. It may be said that three-fourths of the book was written by a researcher and one-fourth by a son in a kind of symbiosis of scholarly and familial subjectivity.

“I traveled extensively, giving lectures about my father, and I saw the interest that he generated. At the same time, people seem incapable of understanding how a person could have earned so much respect from the high- and-mighty, even if it is posthumous. In the book I tried to present Vasyl Stus from my own perspective.”

“What is he like from your perspective?”

“Today it has become very expedient to present the poet as a fighter for Ukrainian independence. But it seems to me that this element was of secondary importance and became apparent only in the last five or eight years of the poet’s life. In the early 1990s, I thought it was important to dissociate the poet from politics, and I did everything possible to do this for ten years, even though already back then I realized that this was also a part of Stus. But if you overstate it without seeing the person behind it, you will create an image of a false demigod. So, I dissociated myself from the political component and primarily accentuated his creative heritage.

“While I was working on the biography, I realized that Vasyl Stus was above all a person who didn’t tolerate disrespectful treatment under any circumstances. He defied the society in which he lived, but it was a universal challenge, because extraordinary personalities have always been in conflict with their societies.

“Most people like that either break down or learn to make big or small compromises. The poet remained true to himself to the very end. I daresay that he was an asocial personality to some degree. The state, which disrespected his rights, had no meaning for him either. Despite this, my father somehow managed to realize himself: he had friends and a woman he loved. Moreover, she was a woman who was content to wait for him. 99.9% of all men can only dream about this. It was very difficult to understand father, which is why instead mother believed him, and waited for him because she believed. To this day she says that Vasyl Stus was not of this world. He created his own world, which is now arousing interest both in Ukraine and abroad precisely because of its universal nature. It symbolized the eternal conflict between the individual and his surroundings.

“However, a different aspect of Vasyl Stus’s life allows us to describe him as a fighter for Ukraine’s independence. He remained faithful to Ukrainian culture despite various temptations to defect to Russian culture. In 1970, when he was deprived of every opportunity in his homeland, he even tried to enroll in Higher Scriptwriting Courses in Moscow and wrote a Russian-language scenario for the admissions committee. However, a call from someone in the Ukrainian Central Committee (I never found out the name), who advised the admissions committee not to accept him, prevented Stus from breaking away from his native land.”

“STUS WAS ONE OF THOSE RARE INDIVIDUALS WHO FULLY REALIZED THEMSELVES IN THE FACE OF ADVERSITY”

“Dmytro, did you understand your father, or have you understood him only now?”

“We had a difficult relationship. After living for five years without my father, I grew accustomed to being just with my mother. We had more of a teacher-student relationship, and the student was far from bright and very slow on the uptake.

“I love the paradoxes of Blaise Pascal, the French mathematician, physicist, and philosopher, who said that the growth of knowledge is like an expanding sphere in space: the greater our understanding, the greater our contact with the unknown. In principle, I can’t say that I understood my father. Getting to know someone is a never-ending process, but I’m interested in knowing Stus as a father, personality, and poet.

“Three years ago I thought that the path chosen by Vasyl Stus offered few prospects. I saw the price my mother, grandmother, and grandfather had paid for the choice he made. He even wrote about this in his letters: ‘Our relatives are worse off than we are.’ Now I tend to think that this is a way of preserving one’s true self, no matter if you become a celebrity or an ordinary folk philosopher, the kind that can be found in every Ukrainian village where they are known as local sages. And these people are equally great, because the caliber of a personality is determined by God. And it is up to you to realize your potential in a specific, predestined setting. Vasyl Stus was one of those rare individuals who fully realized themselves in the face of adversity.”

“Dmytro, how are you raising your sons? Do you hold their grandfather up as an example even though you realize that an uncompromising attitude makes life complicated?”

“I only teach them to love the world and the people around them and never strive to do good to everyone, but to select individuals, because you can’t help them all. The rest depends on their will. Vasyl Stus had a steely will. His fate would be too much to bear for a person with a weaker will. I remember my father saying once after he returned from the camps: ‘I am one of the greatest Ukrainian poets of the 20th century!’ ‘What kind of poet are you? Where are your books?’ I asked him in reply. At the time nobody except for a few friends knew about him. I think there are few people who can preserve such unflinching faith in themselves despite being denied recognition during their lifetime. Only people of the caliber of Witold Gombrowicz, Vasyl Stus, and Panteleymon Kulish are capable of this.”

“THERE SHOULD BE A LIVING PERSON BEHIND A BIOGRAPHY”

“Did you examine any biographies before starting on your monograph? What other Ukrainian greats should have biographies written about them?”

“At one time I was impressed by a book about Evita Peron, the wife of Argentina’s president Juan Peron. I read several versions of the life story of the famous 20th century British spy Laurence of Arabia. Among Ukrainian authors, I read Makhnovets’s biography of Hryhoriy Skovoroda, Petrov-Domontovych’s book about Panteleymon Kulish, and Zaytsev’s book about Shevchenko.

“In general, biographies form an ideological component of the state. In other words, biographical writing, which is not being developed in Ukraine, serves to support the state and can be a means of spreading knowledge about this state in the world.

“I would like to read ‘living’ biographies of Nestor Makhno, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and the dissident poet Zynoviy Krasivsky, who was my dear friend. It would be good if there were a biography of Viktor Petrov-Domontovych, one of the Neo-Classicist writers, who collaborated with the Soviet and German secret intelligence services. Word has it that he got himself into a lot of trouble because of his love for Mykola Zerov’s wife, but he married her nonetheless. All of them were creating themselves, constructing their own biographies, and surrounding themselves with friends. I would love to buy a book about Lina Kostenko, another friend of mine. I always tip my hat to her as one of the brightest and most interesting Ukrainian women of the 20th century. I would like to read new biographies of Lesia Ukrayinka and Taras Shevchenko even though much paper has been devoted to them.

“A living person must be present in monographs, but it is very difficult to write this way. Authors mostly lack knowledge of their subject’s emotional life. Researchers tend to go too heavily with either documents or conjecture; hence the many one- sided and uninteresting views.

“Why do we continue to make our high school students dislike Taras Shevchenko? Why don’t we tell them about his victories, instead of focusing on his sufferings? I left school with this lack of love for Shevchenko, and it took me twenty years to learn to appreciate his Kobzar and understand his works and fate. In order not to appear hypocritical, we often prefer to conceal certain dramatic facts. But culture is vengeful, and when you conceal certain facts, they will be interpreted in literary works of a different sort. I recall the torrent of criticism that was directed against Les Buzyna’s book. But this book, which is most certainly disrespectful to Shevchenko, is also a reaction to the absolutely abnormal state of our literary critique and biographical writing, as well as to our pseudo-chastity. Knowledge cannot be chaste. Respect and understanding is the most we can demand of knowledge. Meanwhile, we are creating little gods. As a result, what we get is either unemotional documentation or fiction that has little connection with documents. Meanwhile, we have so much that is genuine and interesting.”

“A CD entitled ‘The Live Voice of Vasyl Stus’ was released with the backing of Kateryna and Viktor Yushchenko. And the book Vasyl Stus: Life in Creativity appeared late last year. Do you believe that Ukrainian culture will receive adequate state support now that new people have come to power?”

“I kept in touch with the new government while it was still the opposition. They also sponsored the Vasyl Stus Center for the Humanities. How our relations will evolve is anyone’s guess. So far our work has become more difficult.

“I have no illusions that the new government will introduce fundamental change. Since I work in the sphere of culture, it hurts me to see that neither the deputy prime minister for humanitarian issues nor the culture minister speaks about developing a technology of cultural progress (even though a cultural industry is long overdue), and about the rules of the game and competition in the cultural sphere. While such one-time projects as state holidays or Eurovision contests are run of the mill in the rest of the world, for Ukraine they are overriding goals.

“Now they are discussing the possibility of abolishing the titles of people’s artiste or meritorious artiste, etc. But this issue should be resolved in about ten years, after some alternative schemes have been introduced. After all, these titles provide guarantees for ageing people. Then there is talk of reforming the Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences. What will replace it? After all, Pavlo Skoropadsky established the Academy of Sciences, and it has existed to this day. Before setting about destroying something, you must create something better. But this is not to say that the academy does not need modernization. It certainly does. But so far the level of discussions about such reforms scares me because of its lack of professionalism.

“The situation in book publishing is downright catastrophic. Books that are in demand, Vasyl Stus: Life in Creativity being one of them, cannot be reprinted for the banal reason that publishers are strapped for cash. This is proof of the conditions in which Ukrainian books have to survive in the face of competition from strong Russian, Polish, and American publishers. That’s our life: while some are riding in planes, we are trying to catch up with them on a horse-drawn cart.”

“What would Dmytro Stus have without Vasyl Stus?”

“A world in which he would be free to do mischief without the annoyance of well-wishers constantly whispering in his ear: ‘Behave yourself: you are the son of Vasyl Stus’.”