Seventy years later, the most significant events of the World War II, traditionally extolled by Soviet propaganda emerge in a different light. Today, one can repeat propaganda adages, as well as come up with new data, making it public knowledge, offering one’s concepts. Undoubtedly, some — stubborn, Soviet brainwashed — individuals will be outraged by any such expose. Below I will try to describe only several days of the Ukrainian capital’s life at the time, relying on official documents, memoirs, and my family recollections.

On the evening of June 21, 1941, Lieutenant General Maksim Purkaiev, chief of staff, Kyiv Special Military District, called Georgy Zhukov, chief of General Staff of the Workers and Peasants’ Red Army, reporting that a defector, a Feldwebel of the Wehrmacht, had given himself up to a Red Army border guard outpost and informed that German troops were in position to invade Soviet territory on the morning of June 22.

That same night, the Soviet military districts received Directive No.1. In compliance therewith, at 03.00 a.m., the antiaircraft artillery pieces and [truck-mounted] Maxim quad machineguns, serving as small-caliber antiaircraft weapons, were manned by crews of the Third Antiaircraft Division. At 03.10 a.m., Kyiv-based night fighters were on red alert. At dawn, the commanders of the 2nd and 43rd Fighter Regiments ordered a squadron airborne each on blue alert missions. The civilian population, of course, didn’t have the slightest idea about what was happening. People were sleeping in their homes, knowing that the following day they would attend the ceremony of opening the Nikita Khrushchev Stadium (currently the Olympic Complex to host 2012 soccer events).

As reinforcements for the aircraft already airborne, six Polikarpov-1-16 fighters of the 255th Fighter Regiment and five Chaika-1-153 ones of the 2nd Fighter Regiment took off from the airfield in Borodianka. Six rivercraft of the Pinsk Flotilla, deployed on the Dnipro near Kyiv, received battle stations orders.

Unlike the frontier military districts, where a number of Red Army officers were confused by contradictory prewar directives and, fearing purges, hesitated before giving combat orders, the artillery guns in Kyiv opened fire at the sight of the aggressor.

On the morning of June 22, 1941, the aircraft of the 4th Luftwaffe Fleet hit Target No. 12, Kyiv, dropping bombs on peaceful city districts, production and military facilities, including the NKVD barracks, the military college in the Pechersk downtown district, Bilshovyk Engineering Works, power plants, Aircraft Plant No. 43, railroad station, the airfields at Boryspil, Hoholiv, Hostomel, Zhuliany, and Kyiv Airport in Brovary (destroying the main building).

Red Army pilots reported large groups of enemy aircraft scattered by fighter attacks and antiaircraft fire, so that only separate enemy planes actually hit the target.

I was four years old at the time. My parents and my elder brother Hryhorii were awakened by unusual sounds and watched from a window of a high-rise apartment building at 14 Kruhlouniversytetska St. all those Chaika 1-153 biplanes fly with AAA shells exploding all around them. This made my father assume it was a dress rehearsal of the sports event (traditionally every such event was largely a military show) scheduled for June 22. But then the phone rang. It was my father’s friend who lived in Podil. “It’s war! They’re bombing Podil!” he shouted.

According to official statistics, 22 people were killed and 76 wounded that morning in Kyiv. Among those killed were Bilshovyk workers, as one of the bombs hit the iron foundry. The next day the engineering plant witnessed a rally of mourning and patriotism and then 17 coffins were carried to a civilian cemetery in the Lukianivka city district. During the burial the lid on one of the coffin suddenly moved. Foundry worker Ivan Makhynia, presumed dead, turned out to be severely concussed and came to moments before being buried alive.

That morning bombs also exploded on Kozlovska St. and my brother went there to watch ruined buildings, huge bomb craters, with feathers from ripped pillows still flying around. Eyewitness accounts mention other bombing sites on the first day of the war in Kyiv: near the underground headquarters of the KyUR (acronym for the Kyiv Fortified Area) in Sviatoshyn and on Povitroflotske Shose Avenue, where presumably the Kyiv Special Military District Command (KSMDC) HQ was located in a basement of the Engineering Construction Institute.

There are stories about a Luftwaffe plane shot down over the Grave of Askold and that the pilot parachuted, was captured and brought to the KSMDC HQ at 11 Bankova St. This is hearsay, considering that the first German plane, a Ju-88, was shot out of the sky with the first round from a 76.2 mm AAA gun on board the monitor Verny. What was left of the plane was photographed by war correspondents. These photos were carried by many periodicals and are now history textbook illustrations.

The official radio announcement alerting the population to the beginning of war came at noon, eight hours after the German invasion. It was made by People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov in Moscow. He said, in part: “German troops attacked our country, attacked our borders at many points and bombed from their airplanes our cities: Zhytomyr, Kyiv, Sevastopol, Kaunas and some others, killing and wounding over two hundred persons.” Over two hundred. Exactly how many?

“The dawn of June 22, 1941, brought what the Soviet people were scared even to ponder – the beginning of a great war and great suffering. The stunning news… split up national history into three epochs, the prewar, wartime, and postwar ones,” writes the historian, Mykhailo Koval.

Rumored at first as some large-scale military exercise, the harsh reality dawned on people long before the official announcement.

Fedir Khudiakov, a resident of Kyiv, recalls hearing a peasant woman say at a bazaar that morning: “That’s no military exercise, that’s war! We were on the train passing through Post-Volynsky and we saw those planes dropping bombs, I saw them explode and watched killed and wounded people being carried on stretchers.”

Koval quotes from Olena Skriabyna’s diary: “Molotov’s speech sounded hesitant, with pauses, then he would speak quickly as though short of breath. His encouraging words sounded absolutely empty. The instant impression was that a huge monster was slowly approaching you, paralyzing everyone with fear. After hearing it I ran out on the street. The city was panic-stricken. People would meet, exchange a few words and then rush to the nearest store to buy everything they could lay their hands on. People were running up and down the streets. Many dashed to the local savings bank offices to draw everything they had on their accounts, but payments had been suspended. Then by the evening everything became unnaturally quiet, as though everyone had hidden from the terrifying reality.”

Toward the end of that day Zhukov was in Kyiv, visiting Khrushchev on Mykhailivska Square, where the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine was then located. The Kyiv Special Military District was reorganized as the Southwestern Front and placed under the command of Colonel General Mykhailo Kyrponos. Its headquarters was in Ternopil.

On June 23, Pravda carried the program article “The Great Patriotic War” by Yemelian Yaroslavsky (Minei Gubelman). From then on this would be the official Soviet appellation of the war between Germany and the Soviet Union. The article appeared in other newspapers that came off the presses on Tuesday, June 24 (Pravda was the only one to be published on Mondays, with all the others having a day off). All newspapers carried the front-page Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on mobilization binding on “all citizens liable for call-up, born in 1905 through 1918.” June 23, 1941, became the first mobilization day.

Although the decree clearly stated the military age, my father (born in 1902) was drafted on June 23, as were some of our relatives born in 1901, even in 1898. Our family archives that survived the Nazi occupation show that on Monday, June 23, 1941, my father was issued a certificate at his place of work to the effect that he was relieved of his job owing to enrollment in “a course of training with the Workers and Peasants’ Red Army,” and that he had received severance pay in full and issued government bonds and his record of employment. That same day he went to the local recruiting office at a secondary school at 1 Darwin St., where he presented the certificate.

There is also a certificate my mother received from the Lenin District Military Registration and Enlistment Office, dated July 10, 1941, to the effect that her husband “Comrade V.F. Malakov, army officer in reserve with the Lenin District MREO, has been drafted into the WPRA under the Decree of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of June 23, 1941.” On the reverse side, head of the MREO finance department, wrote: “Paid 250 rubles for three dependents for July, as per Order No. 242 of the People’s Commissariat of Defense.” The same sum was paid in June when the term “dependent” was no longer used.

Such official documents show how older men were mobilized under the pretext of military training courses. That time 200,000 residents of Kyiv were called up. Far from all were destined to return home… Fortunately, my father was. He returned in 1945, holding the rank of senior lieutenant, with a Medal for Combat Service. Later, he was conferred one “For the Defense of Kyiv.”

Getting back to the subject, on June 24, 1941, Izvestia published Vasilii Lebedev-Kumach’s poem “The Sacred War.” As soon as the composer, Aleksandr Aleksandrov, wrote the music, it was played on the radio and turned into a patriotic anthem of sorts, a song that gives one an idea about the beginning of that war. And I mean the beginning because the subsequent course of that war gives rise to different emotions and recollections. Back in 1941, the aggressor’s “darkened wings” flew “over Motherland” at will, just as the enemy was free to tramp its “spacious fields” [an allusion to these lines from the lyrics: “We will not let the darkened wings / Fly over Motherland… The native country spacious fields / Are not for fiend’s extend.” – Ed.]. In 1942 this song didn’t stir up as many emotions as in 1941, and even less in 1943 and in the remaining years of the war. Like I said, it is a reminder of the start of the war.

This song is also a code word of sorts to the year 1941, considering that other, simpler, less awe-inspiring lyrics — for example, “The Blue Handkerchief” with music by Jerzy Petersburski, composer and artistic director of a Polish jazz band — remain implanted in the memory of several generations. In fact, the “Handkerchief” quickly became a hit, to be performed for years after the war, after Petersburski’s orchestra was “liberated” in 1939 in Bialystok (as the city was annexed by the USSR). However, since the start of the war the original lyrics were changed as follows:

“At dawn on June twenty-second,

At four a.m. on the dot,

Kyiv was bombed and then we were told

About the start of the war.

Came to an end our peacetime,

Now it is time for good-byes.

I have to leave, but my promise stays:

I’ll always be faithful to you.”

As all popular Soviet songs, the “Handkerchief” had several sets of lyrics composed by anonymous authors, so the Kyiv version dating to 1941 remained known only with these first two couplets. The rest is known under a different title: “Seeing Off.” It has these lines:

“Darling, don’t play with my feelings,

Come see me off to the front.

Boys say good-bye

to their sweethearts,

They’re on their way to the war.

All girls are crying,

hiding the tears,

They stay and’ll help in the rear.

Clickety-clack sing the wheels,

Racing away is the train,

I’m on board, you’re

on platform,

Waving a shaky good-bye.”

By the way, at the time they waved moving a palm up and down. It was in the 1950s that we borrowed from the West the habit of waving good-bye moving a palm left to right.

Years, decades after WW II new publications shed a new light on all those official accounts of feats of arms that were actually legends composed to uphold morale. One such legend is about the first ramming a la Nesterov in a dogfight over Kyiv, performed by Dmitri Zaitsev of the 43rd Fighter Regiment.

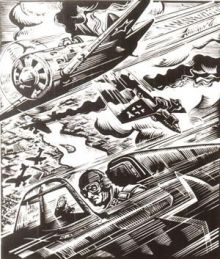

Dmitri Panov (1910-94), ex-fighter, veteran of air battles in China in 1939, then during the defense of Kyiv in 1941, wrote: “On the first day of the war Dmitri Zaitsev, formerly a pilot of my flight, then with the 2nd Air Regiment, whose squadron relieved us on June 22 over Kyiv, engaged enemy bombers in the second half of The Day and did the first ramming at the Southwest Front. The official account has it that Zaitsev — a snub-nosed Russian fellow — cold-bloodedly cut off a Junkers’ tail unit with the propeller blades of his Polikarpov-1-16, whereupon he had to do a forced landing. The Junkers fell near Radomyshl, along the route of the Luftwaffe bombers. The German pilots’ blood-covered flight suits and onboard machineguns were brought to our airfield, apparently to lift the morale. According to Zaitsev (then still to be made Hero of the Soviet Union and entered into the official good books), what actually happened was that, after sideslipping to increase speed, having done this rather effectively, he caught up with a Luftwaffe bomber that had fallen behind formation after a left turn and opened fire with all four Shpytalny machineguns (each with what was then an excellent rate of fire: 1,300 rounds per min.). However, after long bursts this machinegun tended to jam and had to be reloaded by pulling the rings at the pilot’s feet, attached to the thin cables leading from the cockpit to the gun. The attack proved good as the bomber’s rear gunner was apparently dead, the barrel of his machinegun facing skyward and immobile. The other gunner up front had also ceased fire. However, the Junkers had a sturdy hull and the Soviet small caliber rounds couldn’t do any serious damage. To make things worse, all four machineguns did jam in the end. Zaitsev bent down and started jerking at the rings, thus losing sight of where the plane was headed. While he was fumbling with the rings, the fighter caught up with the Junkers in several seconds and its propeller cut into the tail unit. As often happens in life, he would have hardly pulled off a stunt like that, had he meant to. But then the propeller blades cut off the rudder and the elevator. The bomber immediately dipped and went into a deadly spin.

“After landing, Zaitsev found himself in the right place at the right time. Several days later a decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR conferred on him the title ‘Hero of the Soviet Union’ along with the Gold Star Medal and Order of Lenin, in recognition of his feat of arms. This made headlines, the propaganda machine had a field day, and it was instantly clear that flying and fighting, risking one’s life, didn’t fit into such a hero’s image. He had to be made invulnerable to the Nazi aces. Zaitsev was promptly appointed as commander of an air defense fighter regiment in the city of Gorky where Luftwaffe aircraft could be seen probably only on red-letter days and where he stayed until the end of the war, drinking vodka and enjoying the traditional Russian bania sauna.

“Our situation, in contrast, left much to be desired. On the very first day of the war we had to fly three missions to keep Kyiv covered. We patrolled at three-four thousand meters and it was a tiring and nerve-wrecking job, for we expected to engage the enemy any moment, with the incessant noise of the engine. Also, we had to keep watching the ground below. Near the Chain Bridge (a motor transport bridge in place of the current Metro Bridge and Hidropark. – Author) was a huge T-shaped sign with countless small branch pieces and a large white linen arrow. Depending on the position of these signs we determined the enemy approaches to the city because our powerful industry had failed to secure reliable radio communications before the war.”

Today’s reader, who never parts with a cell phone, will find it hard to picture the conditions in which combat operations had to be carried out at the time. Well, that was reality and, although the subject of this article is the first day of the war, I can’t help quoting from Panov further:

“Clearly, our planes were no match for the quick and powerful aluminum covered Junkers that entered Kyiv air space with impunity at an altitude of up to 3,000 meters. Each time we would strain our plywood Chaikas to catch up with them, invariably ending up dragging behind them. The Germans acted as though we simply weren’t there.

“I remember the start of the war as a wild bloodletting Theater of the Absurd with drunk yelling idiots in power taking turns jumping out on stage, where everything is done assbackwards, where our people seem to be trying to outdo each other with acts of stupidity and slovenliness. I must admit that the Germans did only half of the job beating us; the other half we did ourselves. Here is an example: during peacetime, when on night training missions, the airfield would be lit by several searchlights, but as the war began, they all disappeared, being taken away somewhere (we were told they were brought to Moscow to reinforce its defenses). So what about Kyiv? There were several searchlights left making up the huge city’s air defense, including one at the Darnytsia railroad station. They made little sense. Even if a searchlight caught an enemy aircraft in its beam there was no way we could fly up and intercept it because we couldn’t land on an airfield without searchlights. As usual, Moscow came first, the only place where, so the Muscovites believed, something serious was happening, meaning the rest had to rely on their own resources.” Well, the situation doesn’t seem to have changed much since then.

Further on it is also clear that not all of Kyiv AAA crews knew to tell a friendly from an enemy aircraft. Apparently they had no access to the Moscow-published album “Warplanes of the USSR” (1940) with each aircraft presented in three projections and at eight photo angles, airborne and on the airfield. The foreword reads: “This album is intended as a reference source, so the contours of the USSR warplanes can be correctly identified, while airborne, by Red Army ground troops, VNOS (Russ. acronym for air defense monitoring, early warning and communication) stations, and by Red Army aircraft crews while airborne.” This album was signed for publication on October 4, 1940, so in all likelihood its copies hadn’t reached all the addressees before the start of the war.

Getting back to what was happening in the sky over Kyiv in the summer of 1941. Here is what Panov has to say on coordination between the air defense units.

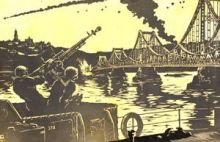

On July 22, three Ju 88 nine-aircraft formations flew in from the south to bomb-raid Kyiv bridges across the Dnipro. They were challenged by a flight of Chaikas led by Panov and forced to drop the bombs on a ravine known as Telychka, instead. The Luftwaffe aircraft immediately flew west while the Chaikas found themselves amidst friendly AAA barrage flaks. The artillery crews down on the ground had to identify friendly aircraft immediately, because [the Soviet plywood] biplanes were so different from Luftwaffe [aluminum] monoplanes, the more so that they had seen such biplanes patrol the city from day one of the war. Also, the Chaikas waggled their wings as a signal of being friendly aircraft. As it was, they sustained four AAA salvos before landing.

Panov wrote: “Friendly fire, unlike enemy fire, proved far more effective.” A shell fragment punctured his oil tank, splattering hot oil over the cockpit, smearing his goggles. The engine started overheating, doing so quick enough to make forced landing the only option. He managed to land in a wood-cutting area on the Left Bank without releasing the undercarriage. The plane caught on a tree stump and the pilot survived by sheer miracle. The next day Panov visited Kyiv’s AAA crews to “thank” them for their performance and warn that if his Chaikas were shot at again, his plane crews would also get confused and launch a series of jet-propelled projectiles at the AAA positions. Fortunately, no such occasion proved forthcoming.

Out of many public events scheduled for June 22 in Kyiv, only the ceremony of opening the Khrushchev Stadium was canceled, along with a Kyiv Dynamo vs. Moscow CDKA (Central Red Army House) soccer match. No drama plays or movie screenings were canceled on June 22-23 — and this despite the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR imposing martial law, as of June 22, on almost the whole European part of the Soviet Union, including Ukraine! Soviet society, lullabied by official propaganda reiterating that the nonaggression agreement (subsequently to become known as the Motolov-Ribbentrop Pact) was mutually advantageous and inviolable, must have failed to fully grasp the scale of the imminent threat.

Kyiv production facilities, research centers, higher educational establishments, government institutions started being evacuated, along with staff members and their families, on June 29. A total of 325,000 Kyivites traveled east, deep behind the Soviet rear lines. On July 11, advance units of the Sixth Wehrmacht Army approached the river Irpin marking a direct approach to Kyiv. Thus started the heroic and tragic defense of the Ukrainian capital that would last for 70 days and nights and save Moscow from being seized by the Wehrmacht before the coming of winter — which is a different story.