Deceive your children, if you will;

Your friend, that simple clod;

Deceive yourselves and foreign folk;

You cannot cozen God!!

The communists have always accused their political adversaries of “shooting them in the back.” This accusation has been applied at various times to the so-called treacherous peoples of the USSR, Poland’s Armia Krajowa, the Baltic “forest brothers,” and generally to all those whom Stalin could not control.

Although it was not possible to say this to the Western allies, they were accused of hatching a conspiracy with the Nazis behind the USSR’s back (the subject of the popular TV serial Seventeen Moments of Spring, where the Soviet spy Stirlitz tries to expose the US-German secret talks on a separate peace treaty) and not helping the Soviet war effort enough by waiting for the Soviet Union to exhaust itself.

But the communists maintained a discreet silence about the fact that the USSR concluded the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and was supplying Germany with material resources in the heat of Hitler’s offensive in Europe, and that the West’s Lend-Lease program, although it did not play a decisive role in the victory, came to the USSR during the most critical days of the war, when it was desperately needed.

As for “shooting in the back” of the Soviet Army, this was the handiwork not of the mythical “UPA bandits” but the communists themselves. Recall the notorious Order no. 227 of July 28, 1942, authorizing the formation of penal battalions and barrier troops in which 427,910 men saw service. Most of them were killed in action or became disabled (see, the statistical reference book Russia and the USSR in 20th-Century Wars edited by Col.-Gen. G. Krivosheev, Moscow, OLMA-Press, 2001).

1. DEATH AS PAYMENT FOR MISTAKES

Barrier units were not only stationed behind the culprits’ backs. Their main task was to inspire terror in Soviet soldiers and prevent them from retreating from the battlefield. They did not take into account the fact that a retreat was likely not just because of panic but also because of the simple inability to contain the enemy with the available means. Soviet troops had to pay with their own deaths for the top leadership’s mistakes.

Not a single work of fiction or research on the war has failed to note the fact that there were machine-guns in the rear shooting Soviet troops. There is not a single positive reference to those units, and only in exceptional cases did they join the regular troops and take part in combat. A barrier unit commander could be punished for this because his main duty was to shoot “in the back” of the Soviet army rather than at the Germans. So “veterans” prefer to remain silent about having served in those units.

The first screen units were formed in July 1941. Purkaev, the head of the Political Directorate of the South-Western Front, reported to Mekhlis, the chief of the General Political Directorate of the Red Army, about the way they were holding back the troops retreating toward Kyiv — by shooting some and forcing others to return to the battle area and halt the retreat. This was the period when the Germans had inflicted a defeat on the South-Western Front troops in a borderline battle and reached the remote approaches to Kyiv.

Georgy Zhukov also formed barrier units on the North-Western Front (the order is dated Sept. 17, 1941). From the summer of 1942 they were formed everywhere. These units usually survived, while the entire personnel of a formation might be killed in action. For example, when the Germans broke through to Stalingrad on Aug. 23, 1942, it was impossible to defend the North Caucasus because of the complete absence of reserves.

Attempts to throw the remnants of the defeated troops against the Germans produced an interesting result. The 37th Army comprised 4 rifle divisions with only 500 to 800 men each. What remained of the 56th, 9th, and 24th armies were only their headquarters and “special units,” i.e., barrier detachments. This information is taken from the book The War Years by Andrei Grechko (Hrechko), Commanding Officer of the Novorossiisk defense area and later the longtime Soviet Minister of Defense and Marshal of the Soviet Union.

The communists delivered a mighty stab in the back of the Red Army even before the war. Repressions against the military began well before 1937. In his speech at the plenum of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik) (CC AUCP(B)) in February— March 1937, the People’s Commissar for Defense, Kliment Voroshilov, admitted that 22,000 officers had been dismissed from the army in 1934-1936 for political reasons.

A random check of their further destiny shows that most of them did not survive the 1937-1938 reprisals. Since they were executed by decision of “NKVD extra-judicial bodies” as civilian “enemies of the people,” they were not included in the statistics on the repressions in the army. Another 36,761 commanding and political education officers (about 40,000, including naval servicemen) of the Armed Forces were repressed in 1937-1939 (see the Russian journal Voenno-istoricheskii Zhurnal, 1993, no. 1, p. 56; and O. F. Suvenirov, “An All-Army Tragedy,” in the Soviet journal Voenno-istoricheskii Zhurnal, 1989, no. 3., pp. 39-47). A total of 19,868 were arrested.

It is common knowledge that Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky, who was a division commander at the time, was tortured into confessing that he was a Polish and German intelligence agent. Officers stationed in the Far East and the Caucasus were often accused of collaborating with the Japanese and Turkish intelligence services, respectively. Military districts virtually competed to expose the highest number of “enemies of the people.”

The exact number of Soviet army personnel is still unknown. In order to grasp the extent of the powerful blow that was struck against the officers corps — the backbone of the army — one should be familiar with the following statistics: 3 out of 5 marshals, all 11 deputy defense commissars, 98 out of 108 members of the Supreme Military Council, 13 out of 15 army commanders, 8 out of 9 fleet admirals, 50 out of 57 corps commanders, 154 out of 186 division commanders, all 16 army commissars, 25 out of 28 corps commissars, and 58 out of 64 division commissars were repressed.

On the whole, more than 500 commanders, from brigade commanders to Marshals of the Soviet Union, were arrested on trumped-up political charges in the prewar years (mostly in 1937-1938), 29 of whom died while under investigation (as a result of torture by the NKVD) and 412 were shot. Also repressed were some top defense industry executives and most of the managers and chief engineers of large military plants.

To fathom the unprecedented nature of this extermination, let us compare it with the number of generals who were killed in action during the Great Patriotic War: 180 (112 division commanders, 46 corps commanders, 15 army commanders, 4 front chiefs of staff, and 3 front commanders). In other words, the 1937-1938 terror claimed twice as heavy a toll as the four years of the war combined.

At the very beginning of the war the suicides of Red Army officers became a mass phenomenon, which is explained by the fact that they did not want to carry the blame for the defeats for which the top leadership was in fact responsible. The list of these suicides — victims of circumstance — is very long. General Kotliarov, the commander of the 58th Armored Division, who shot himself on Nov. 20, 1941, during the Battle of Moscow, expressed the current mood in his suicide note: “Overall disorganization and loss of control. The supreme headquarters are to blame. I do not want to bear responsibility for the general mess. Retreat behind the antitank obstacles and save Moscow. There is no sense going forward” (cited in A. Isaev’s Russian-language book, The Debacles of ‘41: The Great Patriotic War That We Did Not Know, Moscow, Yauza, 2005, p. 326).

This was the direct result of the terror that the communists unleashed against their own army, when commanders of all levels were lined up and shot in spite of the true state of affairs. Mekhlis was particularly active in this respect. For example, part of the 34th Army, whose counterattack saved Leningrad from a quick German breakthrough, perished in encirclement in early September 1941. The army commander Maj.-Gen. K. Kachanov was shot in front of the army staff on Sept. 29 for being “guilty” of the defeat. His deputy, Artillery Maj.-Gen. V. Goncharov, was executed on Sept. 11 without a trial.

Nobody took into account Kachanov’s arguments. The reason why is clear. Order no. 057 of Sept. 12, 1941, issued to the troops of the North-Western Front, already contained backdated “proof” of Kachanov’s guilt.

When Stalin, the “Father of the Nation,” shifted the blame for these failures onto his generals, he became a “trendsetter” with respect to their executions. The court-martials and summary executions of the top commanders of the Western Front in July 1941, when generals Pavlov, Klimovskikh, Grigoriev, and Korobkov were shot hours after their “trial,” was an object lesson for the rest: after a defeat it is better to die in action than to take the blame for everything.

A report that Maj.-Gen. K. Golubev, the Commanding Officer of the 43rd Army, sent to Stalin, is a vivid illustration of the atmosphere in those days: “The army has stopped running away and has been punching the enemy on the nose for 20 days...In the heat of combat we had to shoot around 30 men and to be nice to some others...I request you to stop applying the policy of the lash to me, as was the case in the first five days. On the second day after my arrival they promised to shoot me, on the third day-to court-martial me, and on the fourth day-to shoot me in front of the arrayed army” (cited in Dmitry Volkogonov’s Russian-language book, Seven Leaders, Moscow, 1998, book 1, pp. 216-17).

If generals suffered this kind of treatment, then the lives of soldiers were not valued at all. Stalin not only dictated and personally edited the notorious orders nos. 270 and 227, but also demanded that all commanders submit daily reports on their implementation. If there were not many executions, this was regarded as insufficient effort to maintain discipline in the armed forces. Every day the political education chiefs of fronts and armies reported to Moscow on the “work” of the barrier units.

Stalin’s order in fact copied an idea from Leon Trotsky, who said in 1918 that it was impossible to build an army without repressions: our soldiers, he claimed, should be put in a situation where they have to choose between a likely (but honorable) death in action and an inevitable (but shameful) death in the rear.

Summary executions began in Moscow in October and November 1941, when military police literally combed the streets for men of army service age. The repressions were intensifying. On the Stalingrad Front alone, barrier units shot 140 people on Aug. 1-10, 1942 (Volkogonov, p. 219). This occurred when the Germans were advancing, but it was no better when the Soviet troops were on the offensive.

A memorandum from the NKVD Counterintelligence Department of the Don Front, entitled “On the Efforts of Special Bodies to Expose Cowards and Panic-mongers in Don Front Units in the Period from Oct. 1, 1942, to Feb. 1, 1943,” which was sent to Viktor Abakumov, chief of the Counterintelligence Directorate of the NKVD USSR, noted that there were only isolated cases of unauthorized retreat or desertion from the battlefield. Nevertheless, the counterintelligence services arrested 203 people, of which 49 were shot in front of arrayed units, and 139 were sent to penal companies. Another 210 people who were not included in the general statistics were summarily shot “by resolution of special departments.” (This document is stored at the Central Archive of the Russian Federal Security Service and was posted on the Internet on the 60th anniversary of the Battle of Stalingrad.)

In 1941-1942 front and army court-martials sentenced to death a total 157,593 people. This amounts to 16 rifle divisions that were destroyed by the friendly, not German, authorities (Volkogonov, p. 219). The vast majority of these people were “guilty” of being part of a disorganized retreat caused by a disruption in inter-headquarters communication or mistakes made by the top Soviet leadership. They lost their lives because of someone else’s mistakes and were thus correcting the latter. There are no statistics on the number of those who were summarily executed.

At this time the cult of the osobist (military counterintelligence officer) emerged. This type of officer could send anyone to death row or save someone from death. After the war Marshal Rokossovsky tracked down and helped confer an order on the osobist of the 16th Army, who saved his life in the fall of 1941. An Order of the Red Army Banner in gratitude for humaneness and a saved life — yet rank-and-file soldiers were in no position to pay a ransom like this for themselves. This is the way they fought: trapped between a likely death from a German bullet and an inevitable death from a “friendly” bullet from the rear. All they had to do was choose which bullet was sweeter.

This was the continuation of a practice that the Bolsheviks had introduced during the Civil War, when the first Red barrier detachments were formed, commanders’ families were taken hostage, and units accused of cowardice saw every tenth or even third servicemen executed. Terror methods for controlling the army were the very essence of the Communist Party. So who was really shooting in the back of Soviet troops as they were shedding their blood in combat? The UPA, which consisted of Ukrainian peasants, or the NKVD, which was manned by elite, loyal Leninists?

2. AN ALLIANCE OF TWO TYRANTS

While concocting a host of accusations, the communists are loath to recall their own cooperation with Hitler. It was not until the archives were declassified that Moscow ceased to deny criminal conspiracies with the Nazis, such as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the treaty “on friendship and borders,” which positioned the USSR as one of the countries that unleashed World War Two.

When the pact and the supplements to it were being drawn up, the Germans willingly accepted most of the Soviet proposals. They even contemplated the possibility of the USSR joining the Anti-Comintern Pact of Germany, Italy, and Japan (Volkogonov, p. 266). In reply to Ribbentrop’s greetings to Stalin on his 60th birthday, the Soviet leader declared on the pages of Pravda: “The friendship sealed by blood between the peoples of Germany and the Soviet Union has ample grounds to be long-lasting and strong.”

According to this pact, the USSR was to seize the Polish territories east of the Narev-Vistula-Sian line. Hitler was free to invade Poland. “In a few weeks I will stretch my hand to Stalin across the joint German-Soviet border, and we will begin to re-divide the world,” the Fuehrer said.

At 2 a.m. on Sept. 17, 1939, Stalin received the German Ambassador, Count Schulenburg, and in the presence of Molotov and Voroshilov told him that the Red Army was launching hostilities against Poland. At 3 a.m. Poland’s Ambassador Waclaw Grzybowski was summoned to the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs of the USSR. Since Molotov was with Stalin and Schulenburg, the Polish diplomat was received by Molotov’s deputy, V. Potemkin, who read out the Soviet government’s note, which stated:

“The Polish state and its government have in fact ceased to exist, which invalidates the treaties concluded between the USSR and Poland. Left to its own devices and deprived of leadership, Poland has thus become a field for all kinds of accidents and unexpected things that may pose a threat to the USSR. Therefore, having been hitherto neutral, the Soviet government can no longer take a neutral attitude to these facts...” (E. Yaroslavsky, “Whom Are We Going to Help?” Pravda, Sept. 19, 1939).

Then the Soviet government informed the Poles about its next concrete actions: “In view of this situation, the Soviet government has instructed the Red Army Chief Command to order our troops to cross the border and place the life and property of the population of Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia under their protection.”

Evidence of Grzybowski’s reaction is documented. The Polish ambassador refused “to accept the note, for this would be incompatible with the Polish government’s dignity.” So the note was simply sent to the Polish Embassy while the ambassador was at the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs.

An hour later, at 4 a.m. on Sept. 17, 1939, the Red Army’s assault units began to seize Polish borderline areas on bridges. At 4:30 a.m. the artillery opened fire, and at 5:00 the troops of the Red Army’s Ukrainian and Belorussian Fronts launched an offensive operation, striking deep into the rear of Poland, which had been defending itself from the Germans for the past two weeks.

Soviet generals used to recall the joint Soviet-German parade of the victors that took place in Brest in September 1939. But today the communists are trying to avoid all mention of it. The Polish garrison in the Brest fortress resisted for three days, until German and Russian reinforcements came from the west and the east, respectively. Two years hence, the Soviet garrison would be shedding blood in this very fortress, and the Soviet participants in that 1939 parade would die in Belorussia, surrounded by the Germans.

This is how the USSR entered the Second World War. We know about this only too well from the events of June 22, 1941, when the Germans attacked the USSR, with the same characters in evidence: Schulenburg, Stalin, Molotov, Voroshilov, Timoshenko; again 4 a.m. and assault units (German ones this time!) on the borderline bridges. But today’s communists have forgotten similar events on the morning of Sept. 17, 1939.

The USSR’s entry into the war speeded up the fall of Poland. Then the USSR committed an act of aggression against Finland, for which it was expelled from the League of Nations and was finally placed in the same line as Nazi Germany for instigating the Second World War.

3. HOW THE DRAGON “CUT ITS TEETH”

Soviet-German cooperation played an extremely important role in the creation of Germany’s military machine and its first victories. The political decision on military and technical cooperation between Germany and Soviet Russia was made as early as 1922, when a treaty was signed to this effect on April 16 in Rapallo. The treaty envisioned the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries and canceled all claims with respect to World War I.

On the territory of the USSR, the Germans established a number of military research facilities, such as an aviation center in Lipetsk, a chemistry school in Saratov, the Kama Tank School, and a tank testing ground in Kazan, where Germans held full-time positions as managers, teachers, foremen, engineers, and instructors. This was stipulated in the contracts that were concluded with the Soviet side.

Equipment, teaching aids, and manuals were brought secretly from Germany, which also made payments for electricity, fuel, and utilities in the USSR. The Soviet Union provided the Germans with buildings and land for educational facilities and testing grounds, ensuring secrecy of the entire process.

German schools on Soviet territory trained officers for the future Luftwaffe and Panzerwaffe, as well as chemical warfare specialists. Although they were located in the USSR, these schools were subordinated to the Reichswehr’s General Staff, which sent German inspectors to the USSR, who also visited Soviet army units and observed maneuvers.

Among them were those whose names would one day fray the nerves of Soviet leaders. Heinz Guderian inspected the training of commanders of his future tank troops (disguised as “motorized units” in Germany) at the Kazan school. Ten years later Guderian would command an armored group that surrounded Soviet troops near Minsk, Smolensk, and Viazma, and took Tula by storm. During his breakthrough to Moscow, Guderian stayed at Lev Tolstoy’s Yasnaia Poliana mansion, stationing his headquarters in the house of the famous Russian writer.

As part of military cooperation, other German officers, who would later give Moscow plenty of headaches and trouble, also visited the USSR: Model, Horn, Kruse, Feige, Brauchitsch, Keitel, Manstein, Kretschmer, and others. Each of these names would be associated in the USSR with tragedies, failures, and heavy losses. Model proved to be a talented tactician, who repeatedly inflicted defeats on Soviet, British, and American troops. Field Marshal Keitel would be tried as a war criminal at the Nuremberg Tribunal and executed.

Manstein would become Hitler’s favorite strategist, who crushed the Crimean Front in 1942 and drove masses of Soviet troops into the Adzhimushkai quarries. He took Sevastopol by storm, pushing the 100,000-strong Soviet army toward the Black Sea (party bosses and generals narrowly escaped from the city on airplanes and submarines, leaving the troops to their own devices). In 1943 Manstein would lead the German offensive on Kursk, where Model also distinguished himself. This list may be expanded with the addition of the names of the German pilots who were taught to fly and studied air warfare tactics in Lipetsk.

Particularly fascinating is the work of the German chemical center in the USSR. The treaty on joint Soviet-German aero-chemical research was signed on Aug. 21, 1926. The USSR was to create conditions for conducting secret experiments, while the Germans were responsible for technological and scientific aspects; they also managed the experiments. They were in such a hurry that they began practical work in late September 1926, when they carried out about 40 flights at the Podosinki testing ground near Moscow. The aircraft would spray a liquid that imitated the action of ypritis, a chemical weapon universally known since World War I.

The construction of the Tomka chemical testing ground near Prichernavskaya, near Volsk in Saratov oblast, was completed in 1927. It became the main chemical warfare center in Europe. This facility developed chemical attack methods, testing new carriers of chemical weapons and new chemical substances, their impact on animals, as well as anti-chemical defense methods. The USSR helped the Germans learn all this to its own detriment.

When Hitler came to power, Germany embarked on abolishing the Versailles peace system. There was no longer any need for secret facilities, so the Germans discontinued their presence in the USSR. They gave all the equipment and machinery at the training centers in Lipetsk, Kazan, and Volsk to their Soviet comrades. The Lipetsk base soon became the Higher Tactical Flight School, which is today the Lipetsk Air Force Center of Russia. In Kazan, the Kama School was transformed into the Kazan Tank School. Tomka became the Red Army chemical testing range (still in existence).

Yet the German-Soviet alliance did not cease to exist. Military and technical cooperation lasted throughout the 1920s and 1930s. From the Germans the USSR purchased some equipment, weapons, and technology, and ordered sophisticated technological complexes (in 1933 the German company Deschimag designed a submarine that was launched into production in the USSR in 1936 as series S).

Soviet orders helped Germany develop its tank, aircraft, electrotechnical, chemical, and shipbuilding industries during the most difficult period in the history of that country, when it had no official right to do such things. Thanks to the USSR, the Germans lost no time and, starting in 1933, they soon built a new Wehrmacht, Kriegsmarine, and Luftwaffe, seemingly out of nothing. Thanks to the USSR, Germany had the necessary facilities for this.

At dawn on June 22, 1941, a train loaded with grain crossed the border bridge in Brest from the Soviet to the German side. A few minutes later artillery batteries fired and Guderian’s tanks rattled from the German river bank.

On the eve of the war, between April and June 1941, the Soviet Union delivered supplies totaling 130.8 million Deutschmarks to Germany. At the same time, Hitler was also delivering heavy supplies. The German industry worked exclusively to meet the needs of the Wehrmacht in the future war against the USSR and to fulfill its economic agreements with the Soviets. But the Fuehrer knew that the USSR would have no time to use the German supplies, and Guderian’s tanks caught up with some of them on the road.

What was Moscow thinking? This is what Joseph Goebbels writes in his diary on July 27, 1940: “The Russians are supplying us with even more than we want. Stalin spares no effort for us to like him” (cited in Novaia i noveishaia istoriia, 1994, no. 6, p. 198 — in Russian).

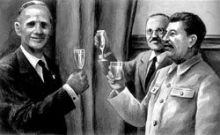

Why did Stalin want so much to be liked by the Germans? Why did he want to prolong the alliance with Hitler as long as possible? Suffice it to recall the sound bites of the Soviet “helmsmen.” Here is a fragment of Molotov’s speech at the 5th Session of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR: “It is not only mindless but also criminal to wage a war for the destruction of Hitlerism, which is covered with the false flag of fighting for ‘democracy’” (Pravda, Nov. 1, 1939). And here is Stalin: “I know that the German people love their Fuehrer. So I would like to drink to his health.” He said this at a banquet with Ribbentrop on Aug. 23, 1939, in honor of the signing of the Soviet-German Non-Aggression Pact. Stalin raised the second toast to Himmler.

Let the communists try and find similar actions on the part of the OUN leader Stepan Bandera whom they hate so much and who spent the war in a German prison camp, never to see Ukraine again. So when latter-day communists talk about the “OUN-SS alliance,” let them start with their own party’s responsibility for the Soviet Union’s links with the Nazis, the creation and development of the Wehrmacht, and the beginning of World War II, because they expended considerable efforts to raise the German military juggernaut on their own territory, which dealt a heavy blow to the USSR in the summer of 1941.

Communist leaders have always known how to conceal their crimes brilliantly and lay the blame at somebody else’s door. A total of 356 special groups of NKVD provocateurs functioned in western Ukraine under the guise of Ukrainian insurgents. Declassified SBU documents have revealed the way they were formed and the havoc they wreaked on the civilian populace in order to discredit the UPA.

Similar groups disguised as the UPA were also formed by the Polish communist authorities. Documents to this effect were declassified in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when documents relating to the mass executions of Polish officers were also declassified. For decades communist leaders had been ascribing these shootings, as well as those that took place in Bykivnia (Kyiv), to the Nazis.

What the UPA fought for is common knowledge to all those who wish to know this — for an independent Ukraine. “You will either achieve a Ukrainian state or die fighting for it” was the commandment of the UPA fighters. At the same time, Soviet soldiers were sent into battle under the slogan “For the Soviet Fatherland! For Stalin!”

The USSR no longer exists. History has issued its verdict on Stalin and his crimes. So who is right — the communists or Ukrainian patriots?

Ivan Diiak was a member of the Ukrainian parliament, 3rd convocation