The UT-1 National Television Company’s documentary studios have completed work on a new film entitled Mykola Amosov: Thoughts and the Heart, which will soon air on television.

“There is no village without a righteous man” is the hallmark and image of Mykola Mykhailovych Amosov. He was an ordinary man with all the usual human flaws and life temptations, but his was an unusual vocation. His tuning fork of conscience had an absolutely clear sound. He did not plan on becoming a great surgeon or a noted cyberneticist, nor did he ever intend to become a bestselling author. Yet he was destined to combine all these skills brilliantly.

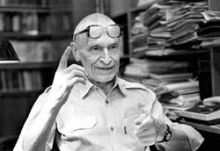

The opportunity to see him again, to hear his voice, to admire his infectious smile, and to sense his singular personality is a joyous event. An opportunity to encounter the great man again is now provided by UT-1’s new documentary (script by Natalia Kovalenko; directed by Liudmyla Pavliuk; cameramen: Valentyn Yurchenko and Feliks Shevardin).

There is no denying that both Amosov and Yurchenko are looking at us from the past. Pavliuk’s private archives contain unique footage of Amosov, made at one time by Yurchenko, who was one of the Chornobyl heroes. Both are now dead. This never-before-seen footage seems to have been bequeathed to us contemporaries.

The medical research buildings are located above the railroad, on a hill overlooking Kyiv. Amosov and I are hurrying to his surgical department, as though to the accompaniment of Yurii Shcherbak’s old poem: “Amosov is climbing Baty Hill in an easy, practiced way. He is in a hurry because there are three operations to be done on switched-off hearts.”

We pass the viaduct connecting the old and new buildings of the clinic; I am following the surgeon. We are in a ward where Amosov, in his usual warm and friendly manner, but without any baby talk, is gradually coaxing a small patient into a talking mood. At first the boy only shows his fingers when he is asked his age. Then we go to the professor’s office. An older boy is awkwardly thanking Amosov for saving his mother’s life. The doctor laughs: “I thank your mom for making it after all the postsurgical complications.”

It is morning in a nearly deserted alley within the bounds of the city of Yaroslav. Amosov is fighting his ills and age. He is fragile but unswerving. Thirty minutes on the screen shows the whole life and destiny of this impassioned enthusiast. How did they manage it? The secret is love and art.

Of course, the “life-giving water” of this kind of epic is the living image of Amosov, his expression, thoughts, and words. He speaks quickly and precisely, with his characteristic okannia (pronunciation of an unstressed o): “I’ve gone through all surgery, done more than 1,000 partial gastrectomies, some 3,000 lung and intestinal resections, even urological and limb surgeries. I did it all, but cardiac surgery is the most effective.” Another statement dates to 1983: “Every physician and surgeon must constantly be aware of the value of human life, so that no one is tempted to operate on a patient for the sake of surgery. I have always been governed by this rule and performed operations only when it was like having to operate on my son, brother, or mother.”

In fact, Amosov always operated on the most serious cases himself, taking on all the risks. Some said it was because he didn’t trust anyone, while others said it was because he was a very responsible man. He never rejected even hopeless cases. He knew the likely outcome, yet his desire to defeat death prevailed. It was a horrible day when a postmortem was done on a little girl whose death was his fault. This experience would beget the opening lines of his book Thoughts and the Heart. Surgery was both his happiness and torment.

The many facets of his life are known throughout the world: Amosov was the designer of Ukraine’s first pump oxygenator allowing access to a “dry heart.” This invention was followed by antithrombotic mitral valve prostheses. Then there was an explosion in a pressure chamber and a human life was lost. Later he refused to do a heart transplant, unable to step over the ethical threshold of having to extract a living heart from the body of a doomed woman. Keeping these memories to oneself is one thing, but confronting Amosov’s passion on the screen is altogether different. The film crew found an unerring and exciting approach. They take the viewer on a journey with people who knew, loved, and worked with Amosov.

Prof. Leonid Sytar recalls: “I performed the Soviet Union’s first operation to replace a patient’s aortic arch. Amosov asked me to call him after I was through, no matter what time. The operation began at 10:00 a.m. and ended at 1:00 a.m. I called him and he asked: ‘Is the patient alive?’ I said he was. ‘Does he have any urine?’ I said he did. ‘Do you?’ Passing urine means that you are alive.”

The film shows Mykhailo Zinkovsky, a pediatric cardiac surgeon and corresponding member of Ukraine’s Academy of Medical Sciences: “Surgery is often compared to art. I can’t say that he did his surgeries beautifully. He did them cleverly and therefore reliably. He was tough, even angry, yet there was an inner intellectual touch to him. He cursed during operations, but he never used four- letter words.”

Hennadii Knyshov, Hero of Ukraine and the current director of the Institute of Cardiovascular Surgery, recalls: “He was a pioneer. This is very important, and performing the first surgery of its kind takes civic responsibility. Another thing that made him extraordinary was that he had gone through the school of war. There one had to make quick decisions. And he was able to do this.”

Amosov’s outward intolerance was actually a democratic attitude. Yurii Panichkin, a pioneer of endovascular surgery, recalls: “We finished working very late and were getting ready to leave. The clinic was empty. We were going down Baty Hill when he started lecturing me again, ‘You did this and that wrong.’ I had the nerve to retort, ‘Aren’t you tired of dressing me down? Why don’t you praise me once for a change? I’m losing heart; I just don’t feel like working.’ To which he replied, ‘That’s because you’ve never put your heart into the job.’ At the time I was in charge of a laboratory.

Amosov had a mathematical formula for happiness. He considered himself to be a dry old stick and believed that the human brain was the engine of progress. In reality he held his emotions in check when he was making hard decisions. He quit surgery several times because of frequent patient deaths and tendered his resignation as institute director, although he could have continued in that post and in surgery for many years. His daughter Kateryna Amosova, corresponding member of the AMSU, who was once a girl in braids, comforting her dad in times of failure, reminisces: “He suffered because everything had come to an abrupt end. Yet he did something extraordinary by his resignation; he pulled himself together and took a timely and dignified leave while he was still at the peak of his career. I don’t think he had any illusions that they would ask him to return, that people would keep coming to him. He realized another thing: the importance of making a timely exit. ‘Yes, I can do operations, but my hands are shaking and others can see this. How can a patient trust me?”

The diaries that Amosov left behind contain a number of confessions and reflections. He wanted to write, but he also had his surgical work. He was aware of his literary talent. Shcherbak recalls: “Speaking of his literature, he told me once, ‘Yurii, can’t you understand that all my operations are worthless? One book will be left and they will remember me by it.’ His Thoughts and the Heart was written by a physician who knew the dramatic aspects of life, his profession, and so he wrote a documentary story. In reality it was written in an innovative literary style, like Arthur Hailey’s Airport or Hotel.”

The documentary film explores Amosov’s legendary exercises, this life-long experimentation on himself, and an operation on his heart that prolonged his life. Fortunately, he died an easy death. Kateryna Amosova dots the i’s and crosses the t’s here.

Was Mykola Amosov a reflection of his epoch? He was perhaps the first and only Soviet citizen to speak nothing but the truth without being a dissident. The regime took advantage of his phenomenon. The historian Yurii Shapoval comments: “Although he was not a member of the party, Amosov was allowed to become a member of the Supreme Soviet and travel abroad. Nor was he forbidden to make bold statements. Of course, it was a dosed sort of democracy.”

Be that as it may, he was the only one in Ukraine to achieve this democracy, within the confines of the restrictions on freedom of ideas. “Amosov is radically different from the current generation, where no step, even against the background of very good relations, is taken without considering money and profit. He was above this.”

During his lifetime Amosov was popular with the people. The fixed-route taxis that traveled to the institute bore the inscription “Amosov Institute,” even though his brainchild had not yet been named in his honor. He is a touching legend of Kyiv, starting with his sudden appearance at the Institute of Tuberculosis in the early 1950s, when he was just an obscure surgeon from Bryansk, and ending with his daily trips to work in a streetcar or commuter train. Most importantly, Amosov left us moral and ethical standards.

The documentary revives these standards, and you watch the film with baited breath. He whose heart was unblemished at all times seems to have been born for eternity. He valued every single day and did not do a single thing to violate his morals. He suffered from his failures and rejoiced in every life he saved, like no one else. It is difficult, next to impossible, to be like him, yet it is necessary. Don’t miss this film.