Kyiv’s Second International Cinema Festival is over. The most “operative” “Left-Bank” journalists spoke about the quality of its competition program the other day after the forum was launched. Only one person in Kyiv was supposed to see it at that time. I beg your pardon sincerely, but it was me, the festival’s program director. Yet I am thankful for this too, I will know for the future, whom to ask for “professional” recommendations, not to waste my precious time selecting films. However, the head of the festival’s international jury, an intellectual and aesthete, great Georgian film director Otar Iosseliani, in a sense, also got into an “awkward situation.” At the festival’s closing ceremony, when he told while awarding the Turkish film Mommo with the festival’s Grand-Prix, that this was probably the best film he had seen within the past two years. He must have been living for too long in Europe, so he did not take into account the pretentious tastes and virtuosity of the Ukrainian press, which is able to write biting critical articles, without going anywhere or seeing anything. I could give you the opinions about the competition’s films expressed by the Hungarian cinema star, winner of the world’s most prestigious awards film director Marta Meszaros, documentary film classic Marcel Lozinski, fashionable Hollywood director, our fellow countryman Vadim Perelman and other members of the jurors’ board, who belong to various schools, are of different ages and have different tastes, but I won’t do this. The caravan keeps going. I hope you understand me.

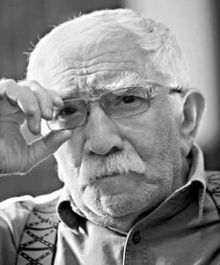

Destiny was kind to me, and I spent the festival week communicating with the members of the jury. One can hardly imagine a better school, without exaggeration, any international film review could envy this lineup. I have told you several names. Besides them, the jury of the main competition included talented Ukrainian artist Serhii Yakutovych, Turkish director Aydin Sayman – a real boom of high-quality and deep film production is taking place in his country, and also the favorite actor of all generations on the terirtory of the former Soviet Union, Armen Dzhigarkhanian. In spite of an extremely tight schedule, my position helped me do what my fellow journalists at the film festival could not, to speak with these people. You may read in The Day’s pages what we talked about at our gatherings.

Armen Dzhigarkhanian left Kyiv before the festival’s closing ceremony. He was urged on by the problems that had accumulated in Moscow during his absence. Waiting for the car that was supposed to bring the actor to the airport, we were sitting at the cozy terrace of the hotel Riviera. This was The Day of Kyiv, and an endless line of people eager to show themselves on Andiivsky uzviz was standing near the funicular railway. Dzhigarkhanian paid attention to it, asking what was above. This was a mistake whose consequences might have prevented this interview from taking place. Before I replied, some particularly curious people threw a glance at the flourishing terrace. Of course, they recognized Dzhigarkhanian. Suddenly, the flow of people storming the funicular, changed direction. Dzhigarkhanian was nice, witty, and friendly. He was photographed with grandchildren and wives, gave autographs for absent fiancees, posed, patiently waiting for the phone’s owner to delete unnecessary data from its memory. The time of his departure was approaching. Yet we somehow found time for a chat.

Because of the stress, apart from the titles of popular films where Dzhigarkhanian has played, the two lines from caustic Gaft’s epigram were persistently popping into my head: “There are many less Armenians living in the world, than there are films in which Dzhigarkhanian has played.” That’s almost true. But what films! Operatsia Trest (Trust Operation), Premiya (A Prize), Kogda nastupaet sentiabr (When September Comes), Zdravstvuite, ia vasha tiotia (Hello, I’m Your Aunt!), Sobaka na sene (A Dog on the Hay), Mesto vstrechi izmenit nelzia (The Place of Meeting Cannot Be Changed) and many others. But there is a fact funnier than the famous epigram: when as a young man Dzhigarkhanian tried to enter the GITIS, he failed because of his Caucasian accent, and had to return to Yerevan where he found a job as a theater lighting technician. At the moment the former lighting technician has his own Armen Dzhigarkhanian Theater of Drama.

ON THEATER AND CINEMA

You have played over 200 cinema roles, and I guess it’s the same with theater.

“I’ve played fewer roles in theater. Let’s not exaggerate.”

What is the most important thing in your life at the moment (besides family and domestic affairs)? What troubles, annoys, excites you most?

“You know, I have a strange profession. (I don’t want to scare people who are contemplating the actor’s future and may suddenly think that I’m discouraging them.) This profession is non-stop. There is no break. For example, in Japan they recommend special pills for plant workers that are leaving the shift, so that they can switch off from thoughts about work. They say it helps. There is nothing of this kind in our profession. You are never out of it. But I don’t mean acting all the time, God forbid.”

But there are people who continue to play off stage.

“Those are bad artistes. They have a surplus of energy. By the way, there is a definition that the most important thing in acting is to keep to the law of energy. Its difficult to control yourself – if you’re good at proposing toasts or telling jokes, you may lack energy on stage. That is why I call my profession a strange one.

“It’s also why I make no distinction between theater and private life. Of course, I can go to see my friend, watch football, yet my psychophysics (pardon the brutal word) is still aimed at observing. It has happened that people got irritated when they noticed that I was spying on then. Even now, as we are talking, I am thinking to myself: ‘She’s wearing leather, looks nice. Maybe I should try and put similar clothes on an artiste in some performance.’”

This is reassuring to hear, that there’s some use of us, obtrusive journalists. By the way, you mentioned your artistes, actors of the Armen Dzhigarkhanian Theater, that you have been heading for 15 years already. This job takes much time and strength. Is this the reason why you have practically stopped to play in theater?

“This is not the reason why I have stopped performing. I’ve simply grown too old for it. It reminds me of the wise phrase, ‘Life takes too much time of a man.’ Or, maybe, I have played enough. For I have had difficult roles. Physically. I would even lose weight for some performances, three or even more kilograms. I have no longer this itching, when I want to capture, seduce, cheat on somebody. This is all part of the actor’s profession, therefore I guess I have none of this left.”

How could it be, if you have created such a theater?

“I am speaking about my performing on stage. The Armen Dzhigarkhanian Theater is quite a different thing. It is called a ‘distracting therapy’ in medicine.”

Are you satisfied with your fosterlings?

“I will say better, I love them. I love them, and I hope for them. I want to think that they need me. For example, I may stand in a foyer, somebody passes by and smiles at me, and I take pleasure in this.

“I keep telling my actors, like my teacher would teach me, ‘Come to the theater to lick the wounds.’ For, if ones gives it a thought, cinema is just consumption. There is no love in cinema or television. I have been playing in cinema for a long while, so I may assert this with proper responsibility.

“And there is love in theater, especially in the Russian one. Theater is my home, the truth is living there. However, it has appeared to be an extremely complicated organism, although it may seem very simple: you’re supposed to weep here, and laugh – there. Yet theater is a strange institution. I cannot find any other definition.”

Was it out of disappointment that a crazy idea once came upon you, to create your own theater?

“No, I still love it passionately. But it is hard to manage a theater, because I am a clown by nature. I am speaking seriously, without coquetry. I love theater, where one sticks a false nose and makes their ears jut out. Besides, I have a feeling that the great Russian theater is in a very bad condition. Actually, I am sure about that. I don’t mean the audience who comes from the street, but those who feed the theater.

“Indifference to culture is the same thing as depriving a maternity house of vital products, like bread and butter. It is not profitable, yes, but children are given birth there. This is the greatest possible reward. God grant that I’m mistaken. I am leaving your charming city, not having waited until the festival’s end, because my theater needs reconstruction, and today I have an appointment with a very influential person. I am having this uneasy feeling, will we come to an agreement or not? For the theater brings no profit. Whenever I ask for assistance, I always warn that I won’t return the money I receive. One can do this in cinema, because films are sold. But in theater – no. That is why I have compared it with a maternity house. I tell you seriously: children are born in both of these places. Whether we like it or not, this is life. There can’t be otherwise.”

As far as I know, at the beginning you organized your theater with graduates of your studying course.

“Not everything happened as it was supposed to. I was warned by old masters, specifically the very experienced theater director Andrey Goncharov, with whom I have worked for 27 years, ‘A theater cannot come out of one course. It can’t.’”

What about Tabakerka?

“No, sweetheart. I can give you 126 more examples, but I will repeat myself, a theater is a complicated institution. Actors tend to change before my eyes. For example, a girl comes to the theater: she’s delightful. Then she gives birth to a child, and the girl becomes a mother: this is another image, a different kind of role.”

Who, in your opinion, is the most successful actor in your theater?

“I am not going to tell this, because we teach people to love each other. I will tell you a secret, and you will find your own words for this: it seems to me I have contributed to all the ‘children’ that have been born in theater. Do you understand me? One day we put up photos of the ‘children’ who have appeared in the period of the theater’s existence. It was very interesting. By any philosophical categories applied, one may assert for sure, who and how much has contributed to the genetic code. Theater is a strange thing, believe me. I know this for sure: I have dedicated a large part of my life to it, I have lived within it.”

CONTEMPLATIONS

I remember you once said that you don’t read books, you talk with them. And quoting Seneca about three roads to self-perfection, the first one is the most noble one…

“Clever girl, you know it!”

The second way is copying, the easiest one. And the third one is experience, it’s the hardest. What way have you chosen for yourself?

“Of course, the easiest way is the way of contemplation, but one must be wealthy in order to follow it (laughing). However, speaking seriously, a person (especially in my profession) covers all paths, from copying to experience. And there is no end.”

Again, there is an expression, “Professionalism is the ability to be good in your profession, yet remain a child.” It is clear what being “good in one’s profession” means for an actor. But what does to “remain a child” mean?

“Not to stop feeling surprised.”

What surprises you today?

“That cat, for example (looking at the three-colored, white-red-and-black beauty, graciously wandering in between the terrace tables, where the interview was taking place). I had a beloved friend Fil (a Siamese cat. – Author), who has lived for nearly 20 years in our place. Do you know what I’ve learned from him? The most important thing in my life: a straight line is the shortest distance between two points. For we are usually zigzagging. We are afraid to be regarded as being primitive if we go straight. God forbid.”

You mentioned Fil. Pardon my painful words: I have read that you consider one of the most important deeds in your life to be your flight to America, when your cat died.

“It’s okay. Sadness gives way to a great positive feeling. I will tell you this, risking that my wife will be offended: Fil was my last love. Seriously. He was living with my wife in America, he was ill. I am a strong, even cynical man. But then suddenly, I was out of breath. I gathered my things one day and flew to America. We spent the night with Fil, and he died the next day (his eyes become tearful).

“Children never stop surprising me. I cannot watch a child cry. Sometimes I even intrude in an incorrect manner, telling the parents that they cannot treat the little person in such a way. They reply ‘It’s none of your business, go away!’

“Besides, I have the theater. Neither Stanislavsky, nor Nemirovich-Danchenko has ever said anything better about the theater than Nietzsche: ‘Art is given to us not to die of the truth.’ Not to die of the truth, and never stop being surprised by life.

“I have many friends, with whom I have been closely connected for years. For example, when I was taking part in the film Tronka in Dovzhenko Film Studio, I made friends with a funny, somewhat awkward man. It seems to me, he was the second director at the time. Now he resides in America, working as a guard at a museum. I have visited him recently. Or, for example, I have been fond of Bohdan Stupka for a long while. He and I have worked together with director Andrey Benkendorf. Today Stupka is the artistic director of a theater, and the president of the international film festival. He is a natural leader. But he’s also a brilliant actor and a good man. I was watching him during the festival, when he was not looking; he had very sad eyes, apparently, he has a lot of problems. Indifferent people don’t look in such a way. I am just astonished at how he manages to cope with all of this. In the morning, fresh and well-knit, he would come to the hotel to greet every guest, tell an anecdote, and leave for a rehearsal. In the evening he performed in Faust, a hard play. The next day his old close friend, actor Les Serdiuk died. Shortly after the prayers for the dead, he had a live show, which ended at 2 a.m. And the other morning, instead of resting, coming to his senses, he went to the showing of the film Ivanov, and soon after that hurried for Iosseliani’s master class. And that was happening every day. You are lucky to have Stupka. He is genuine.”

PRIVATE MATTERS

Your wife is a former actress, and has a critical approach to Dzhigarkhanian the actor. What role of yours, in theater or cinema, does she likes the most?

“I don’t know.”

Have you never asked her about this?

“I haven’t, because I know it is a great ordeal to be the wife of an actor. I will explain. Everything she sees on the screen or on stage are our most intimate reminiscences, because we have no other material. For example, if I play Othello, I play all this with my wife: my love, passion, and hate. And she can see all this, can you imagine? I don’t even know how courageous she must be in order to survive all of this.

“I will tell you more. I have a friend in Yerevan, he’s an old artiste. He said, ‘Never invite and never ask. If they want, they will come. If they want, they will tell themselves.’ For if you invite your friends and acquaintances to your play and ask for their opinion afterwards, they will be forced to lie to you, if they did not like something. I took his words as a principle. Therefore I don’t invite my wife to premieres, what if it will be unpleasant for her? A friend of mine, also from Yerevan, has always asked me two things. First, ‘When you eat in a film or on stage, is this all free of charge?’ And second, ‘When you’re kissing, are your really doing this?’ I would always reply, ‘We kiss free of charge, that’s for sure.’ (laughing)”

Is there any role, in theater or cinema, you can’t play? Speaking figuratively, I am looking at Laurence Olivier and cannot get, how he managed to do what he did.

“Until I’m given the role, I don’t know. If I read it, I will tell whether I can play it. But I will try everything, because it is interesting for me. Once I even told the director to come and offer me to play Romeo, I would come and try. After this expression I began to receive letters saying, ‘You don’t have a proper constitution for playing Romeo.’ I did not envy those correspondents: they have seen only one kind of Romeo, whereas there are many of them.

“My relations with the audience as an actor are endless. I am fond of Chekhov, I consider him the greatest dramaturgist in the world (except for Shakespeare, perhaps). Our performance of his Three Sisters ends with the Masha’s phrase (we found it in the Yalta version of the play): ‘The birds are flying, and will do so for millions of years, not knowing why, until God reveals the secret to them.’ Until God reveals the secret.”

The material was prepared under the assistance of the Nemiroff brand