I was covered with road dust after a many-kilometer march to Piria Rock as I reached Krasnoyarsk late in the evening, when an old acquaintance of mine and a fellow journalist Petro Dubynin said, “Mykola, you are lucky: your fellow countryman Borys Nakonechny returned yesterday from the Eastern Sayan Mountains home, to Sosnovoborsk. He is a well-known hunter, photographer, and writer. I have talked to Borys on the phone. Tomorrow he will be waiting for you. Sosnovoborsk is 40 kilometers away from Krasnoyarsk.”

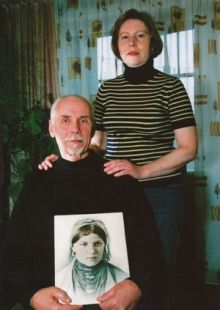

Borys and Natalia Nakonechny’s town apartment smelled of spring taiga, the smells came from the camp outfit and worn rucksack, cedar nuts and two hunting dogs, which sniffed at me and probably thought, “Strange as it may seem, this office man has recently been to taiga and smells of faraway roads.”

Large framed photos under glass, hanging on the wall, immediately drew my attention: a courting display of a wood grouse with fanned tail feathers; a snow-white ermine whose black eyes shine with childish curiosity; an angry glutton and a predatory lynx ready for a final jump. Astonished by what I saw, I asked:

How did you manage to make these photos?

“Frequently I came back from hunting without a bag because of an interesting photo. My dogs were angry that I let the beast go, whereas I was glad that at a proper moment I pressed the button of my Zenit camera, I did not pulled the trigger. These photos won me a silver medal at the international photo contest in Bulgaria in 1980. Incidentally, I got seriously involved in photography when I was working in Kyiv, at the Ukrainian Republican Society of Nature Protection.”

Why did you come to Ural? Was it romanticism or money?

“Both. After graduating from the Kyiv Topographic College I was assigned to Siberia. During long-time expeditions I learned to hunt, fish, and survive in taiga both when it was really hot, and under severe frost. Several years later I came back to Ukraine, because I missed my parents who were residing in the village Piskivka, Borodianka raion, Kyiv oblast. I also missed Ukrainian nature, my relatives and classmates. I even longed for the air and frogs’ croaking. Nostalgia is a mental disease that can be cured only by the dear to heart places of one’s childhood. But later I wanted to go to Siberia again. Such is my character. I worked as a hunter and carried out scientific work in taiga at the commission of biotechnical stations. Incidentally, I sent several very precious items for the exposition of the Kyiv Museum of Nature.”

I asked Natalia Nakonechna:

How did you meet your future husband?

“It was not me, rather it was him who approached me. I come from Borodianka raion too, only from the village Lubianka, and my maiden name is Shaparenko. After graduating from the Kyiv Book Trade College, I worked as a shop assistant at the second-hand book department at the Mystetstvo department store, located in Khreshchatyk. Once my sister and I were going by a trolleybus with a pile of books each, when a passenger rose so that we could put our books on the seat. When he learned where I worked, he asked for my phone number. He said he wanted to see the books we were selling. In the evening he came with a splendid bouquet of flowers. Somewhat later he said: ‘Natasha, I fell in love with you at first sight. I am a professional hunter. I have to go back to Siberia. But I have no apartment there, neither in the village, nor in town, only a hunter’s house in taiga. It is called a winter house in Siberian language. It is located 118 kilometers away from the nearest population center. Marry me. I am a reliable man. I will never leave you.’”

My interviewee was silent for some time. Then she said: “I went with him. From Khreshchatyk to taiga.”

Have there been any dangerous situations in your life? Why did you move from taiga to the town?

“Our life is a constant risk: a car may run over you in city streets, and a beast can tear you in taiga. Once when I was fishing on a lake, the ice broke under my feet. I got out myself. I ran barefoot in the snow from the lake to the winter house. Other things happened too. I worried about my husband when he hunted for two weeks in taiga. And we moved to Sosnovoborsk when our daughter Olena had to go to school, to the first grade. By then she was living with us in the forest. We taught her to read and write, know and understand, and most importantly, feel the nature. Currently Olena is a student of the microbiology department at the Siberia Federal University.”

When was the last time you went to Ukraine?

“We have not been to our native land for a very long time. For nine years. I feel very guilty because of this. My father and Borys’s parents are buried in Ukraine. We took my mother, Motria Arkhypivna, to Sosnovoborsk, when she fell ill. We healed her, a hopeless case for doctors, with medicinal herbs, and she lived for ten more years. She cooked borshch and varenyky. She made friends with local old women, but spoke only Ukrainian with them. When she was dying, she asked us to cover her in the coffin with a rushnyk she brought from Ukraine to Siberia. We did exactly so.”