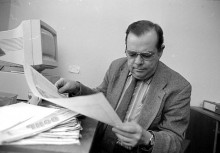

Ukrainian intellectuals, among them people with whom my husband, Dr. James Mace, God rest his soul, used to actively communicate, refer to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine as “hybrid war,” while some scholars in the West have tagged it as information warfare. I believe this word combination most accurately describes what is happening on stage and backstage, considering that when someone wants to conquer a society or get it under control, that society becomes the main weapon against itself, with general population acting as enemy troops. It is then territories are seized without using the latest developments in the military industry. Sometimes this happens without using weapons. This kind of war does not have frontlines, manpower and materiel deployment charts. This is psychological, information warfare, when brainwashing is at the top of the strategic agenda, with the population of the target country serving as the key to its occupation and keeping it under control. Before our very eyes the latest developments in information technologies, the Internet in particular, have formed a new reality where Internet access is regarded as a major vital component in any given society, where it forms it, consumes it, and is the first to fall prey to it. In fact, the Internet isn’t the main point. Social networks first worked offline and became accessible online as the Internet evolved. Dr. James Mace was among the first Ukrainian scholars to spot a change in their paradigms and send the red lights flashing, pointing to Russia’s information war onslaught on Ukraine. He would start each day by scanning through dozens of newspapers and magazines, and sit up nights visiting foreign Internet websites, looking for stories, features, anything that related to Ukraine. I vividly remember his last few days, our conversations. I saw the last vestiges of life being consumed by his anxiety over Ukraine, when he couldn’t speak and used a sign language of sorts, trying to explain what kind of information technologies had been applied in some or other publications, and for what purpose. He could tell whether this or that topic would have a sequel. He could see Russia’s evil spirit in the appearance, in Ukrainian media, of outwardly spontaneous pro-Russia publications/programs, also in the development of the surzhyk Russian-Ukrainian patois. He was constantly outraged by official Kyiv’s sluggish, ineffective information policy. He cursed the temnyky journalists who wrote as instructed from “upstairs,” considering that their numbers were on an upward curve – especially in view of their boot-licking attitude toward Russia. He hated Ukraine’s vacillating national policy. He lashed out at Ukrainian national democrats for failing to attract public attention on a large scale. He noted that the existing Ukrainian regime’s pro-Russia policy had in many ways helped discredit and isolate the most spectacular national democratic figures in sociopolitical discourse, but that there remained lots of opportunities that were being lost each day. I once wrote that James spent each day at a slalom speed. The number of responsibilities he took on were impossible for a single human, even less so for one afflicted with a grave disease. He did, perhaps because he knew there was little time left. He was in a hurry to spot and outline each problem, having no time to resolve it. He realized the importance of identifying an issue, diagnosing a social illness. He hated programs and talk shows with Ukrainian politicians and analysts. “Verbiage! They’re good at sweet-talking Ukraine into doing what they want,” he’d say, referring to politicians who made big and well-worded promises. He would reiterate that none of them had ever spoken the truth about Ukraine being on the verge of going down, that it was high time they stopped rocking the boat; that it was time to gather stones together, time to busy themselves with building a nation-state; that by losing the tempo of economic and social modernization, Ukraine could lose its future.

After he watched the terrorist attacks on New York City he seemed to have entered a new dimension, a new epoch. It was as though he could see the phantoms of future horrors that would befall not only his beloved America, but above all Ukraine which he now loved with all his heart, a feeling that combined a boundless empathy with a people that had survived three Holodomor [Kremlin-architected] famines, countless wars, terror, violence, and a sincere admiration of its culture and spirit that had surmounted all obstacles and preserved the national treasure-trove of songs, poetry, music, architecture. He treated Ukraine the way a son treats his mother. In a way, he held this land sacred… He wanted to protect it against further ordeals and bloodshed. That was his leitmotif as a political analyst, journalist, and Kyiv Mohyla Academy lecturer.

Ukrainian reading public knows Dr. James Mace primarily as a historian and researcher of the 1932-33 Holodomor, as the executive director of the US Commission on the Ukraine Famine (Washington, D.C.), as one who addressed Ukrainian and foreign media audiences, consistently defended the concept of Holodomor as a man-made [i.e., Kremlin-architected] famine, an act of genocide against the Ukrainian state, who revealed its horrors. He was said to be an advocate of Ukraine, an American with Ukraine in heart, a truer Ukrainian than most born in Ukraine. It probably was so because he believed that our dead had chosen him. He was keenly aware of his mission. He came up with a concept of Ukrainian society being a post-totalitarian and post-genocidal one. He relied on that concept when analyzing all of independent Ukraine’s economic, political, and social problems. Few, except a number of regular readers of Den/The Day, know that in his last couple of years James combined academic research with a careful monitoring of political and social events in this country.

At one time, in his features as a political analyst, James stressed an issue that would brutally and unforgettably manifest itself on the Maidan. At the time, he emphasized Maidan’s intellectual aspect.

Since the date of proclamation of Ukrainian national independence, none of the historians, political analysts, few if any of the Ukrainian community at large have held any deep-going debates concerning structural changes in the existing political system. Today we are witnesses to the birth of a mature political society, the emergence of a Ukrainian political nation on the political arena, a nation capable of proclaiming and defending its rights and freedoms.

James reiterated the need in such all-Ukrainian debates, admonishing that by using the word zlahoda [lit., accord] Ukrainian politicians were concealing their inability to face the pressing problems that tended to go from bad to worse. I guess he wrote at the time all he could in regard to practically every aspect of nation-state construction, including the need to decentralize power and resources; about the Ukrainian elite taking up shadow economy practices, Ukrainian kleptocracy, and freedom of the press; about the languages issue and the energy trap into which the existing Ukrainian administration was driving this country by rejecting actual reforms in the field and deviating from the road leading to modernization; about the problems facing small and medium businesses; about oligarchy turning into a systematic problem that would threaten big business in the first place, because of its close ties with power structures and innate merger with upper-echelon bureaucracy would be the first to fall prey to social cataclysms that would inevitably occur because people were being robbed on a nationwide scale. James wrote that big business should help the middle class in every way, even if guided by self-preservation instinct.

I can’t think of a single pressing issue in Ukraine he would miss in his articles as Den/The Day’s columnist and contributor to the journals Politychna dumka, Suchasnist, etc. In fact, he actively collaborated with two strong think tanks that transmitted European political and economic ideas to Ukraine. First, it was Politychna dumka with an editorial staff boasting Ukraine’s top-notch historians and political analysts, among them Oleh Bily, Yevhen Bystrytsky, Volodymyr Polokhalo, Oleksandr Derhachov, Mykola Tomenko, Oleksandr Sharvarok, Oleh Soskin, who took a principled stand and relied on advanced world political and philosophical thought in treating each problem facing Ukraine. Politychna dumka’s articles and books still rank with the best examples of political analysis; they are still topical and serve as textbooks for students majoring in politics, history, and philosophy.

James then started collaborating with Den/The Day and publishing his features as the newspaper was getting momentum, eventually to become a think-tank lab where new concepts of current Ukrainian realities were developed and tested. He had friends and colleagues who shared his views and persuasions, of course. Larysa Ivshyna, the editor-in-chief of Den/The Day said James was her ally and that his collaboration with the newspaper was like the opening of the Second Front in the information realm.

Why such a herculean effort on the part of journalists, analysts, and scholars failed to convey the message to the Ukrainian man in the street? Why no one paid attention to their warnings about the possibility of a systematic crisis, something we’re faced with today? One might assume that all their good intentions were for the birds. He wrote in Politolohiia istorii, abo Narodna osvita yak chynnyk sotsializatsii hromadian (Political History, or Public Education as a Factor in the Socialization of Citizens) that if one wants to seriously consider Ukrainian independence and wishes it to remain a standing consensus, one has to openly use history to help that nation find its political rather than ethnic identity. A nation is a community rooted in the awareness of its common destiny and history; without the lines of demarcation between the history of this group and that of others, there can be no political nation. One has to clearly realize that a nation-state can have good or bad neighbors, but never relatives. Otherwise this would be like holding the door open for various pan-movements, irredentism – in other words, allowing other countries to meddle in that nation-state’s internal affairs.

One would think all that big brainstorm on the part of the Ukrainian progressive intellectual and political community (of which James had so wanted to be a member, so he could influence it [for its own good]) didn’t work.

Despite the bitterness of the current domestic political situation, despite our heavy losses, we should remember the two Maidans. The first was peaceful, well-wishing, dream-inspiring, when people believed in a better future, that all it took was getting together, combining efforts under the right kind of slogans, correctly formulating their demands, electing the right kind of president. The outcome of the Orange Revolution meant only disillusionment, when the man in the street realized that no one “upstairs” would change his life for the better; that this could never happen, even if given a strong political will, because society was to blame for the failure. On that first magically powerful nationwide Maidan they failed to work out effective mechanisms of control over all those “upstairs,” just as nothing was done to make the ranking bureaucrats accountable, legally answerable. Then the Ukrainian man in the street became apathetic, watching the television with bar brawls in parliament and endless political talk shows. The Orange leadership offered the people populism as a cookie instead of concrete deeds, and the people accepted the cookie. Yanukovych’s victory in the next presidential election was often described as a victory of democracy. In my opinion, it had nothing to do with democracy, only the result of the electorate’s fatigue after having too much of populism.

The second Maidan turned into a heroic and tragic battlefield. I regard it as the result of an active effort by healthy nation-building forces. In fact, Dr. James Mace did his best to help them and considered himself part of them. Of course, he never called for revolution or any armed confrontation. He believed in Ukraine’s quick evolution, although he was keenly aware of Russia as a formidable northern neighbor, that it posed a military, territorial, and information threat. Just as it spelled cultural, religious, and economic expansion.

Born across the ocean, in a different cultural environment, James would be outraged by things most Ukrainians took for granted. He was convinced that two political forces – a democratic Europe-minded Ukraine and Soviet-imperial-nostalgic Russia – would inevitably clash. He also foresaw an ideological rift within Ukrainian society. He didn’t want it and hoped that education programs and national democratic efforts would prevent it. However, he couldn’t help predicting the outcome of losing an information war with Russia. Frankly speaking, he wrote in U poshukakh vtrachenoho rozumu (In Search of Lost Brains, 1994), today’s Russia, regardless of the stand taken by its political forces, regards the very existence of Ukraine as a deadly insult. Russia’s political culture and historical memory will never accept Ukraine other than an inalienable part of Russia’s heritage. Russia for Ukraine is the realm of the Ems Ukaz; tsarist and Soviet Russia’s political culture has required constant monitoring of Ukraine, watching for separatism, Mazepism, Petliurism, Banderism, and national identity other than Russia’s. One doesn’t have to be prophet to tell what will happen when Russia is given a free rein in Ukraine. Books will be burned, songs forbidden, and finally men of letters and hungry peasants shot. He went on that he was not born in Ukraine, that his ancestors were buried across the ocean, but that all who knew him would corroborate that he had spent too many years and exerted too much energy dealing with Ukraine to stand aside from the formidable process being underway in that country. He saw Ukraine was in danger; he saw the Ukrainian intelligentsia as the only real national patriotic force capable of combating that process, even though the intellectuals had lost their mass audiences. He saw the only way to revive the political consensus reached on December 1, 1991: by the national patriotic forces of Ukraine mounting their pressure on those “upstairs” to step up actual targeted economic reforms; also, by reviving and expanding Ukraine’s ideological and information space through printed, radio and television media, using creative, education, and other structures – not for spreading empty-worded slogans or lashing out at the ideological opponents, but in order to organize a true state-building process.

In his feature for Den/The Day, entitled “Europe: The Materialization of Ghosts” (recently reprinted by Den) he wrote that the Crimean problem in Ukraine was on an increasingly upward curve; that the Ukrainian central government, after losing the information space battle to Russia’s chauvinists, was unable to have a dialog with the residents of the peninsula and thus try to win their support. Under the circumstances, James stressed, the most important thing was for official Kyiv not to mount pressure on Simferopol but keep explaining what problems the peninsula would face if and when Crimea would part with Ukraine; that this would be a catastrophe followed by mass migration from the peninsula. There was only one civilized way to solve the problem: win Crimea’s information space; only one war that could and should be fought there: win the hearts and minds of the populace.

I keep thinking back to 2004 when James was in a very bad way and yet kept actively corresponding with politicians in the West, analyzing and discussing the consequences of the Party of Regions coming to power. I still wonder what made him so worried about that party. Probably because he thought that a political party made up of people provided by the territorial elites, strongly reminiscent of Stalin’s Red Directors and centralized CPSU, was devoid of any national patriotic concepts, that it would inevitably adopt the worst Soviet bureaucratic traditions; that by nature it would follow the well-trodden path and corrode the national core of the Ukrainian state. Given Russia’s potential threat, all this could end in disaster; local big business’ thirst for easy money, scorn for law and rules of business games would inevitably give a fresh impetus to corruption that would as inevitably lead to an angry social outburst. Russia would use any public disorder in Ukraine to its advantage, so it could increase its pressure on Ukraine. James never took an anti-Russia stand, yet he saw and wrote that Russia’s democracy was a weak sprout compared to the powerful bureaucratic-military-police machine inherited from the USSR and geared to monitor command economy and carry out any [Soviet] imperial subjugation, enforcement, and control missions.

The Orange Revolution put off that threat for almost 10 years, but didn’t eliminate it. During that period a Ukrainian political nation was born, just as another anti-Ukrainian criminal, destructive force took shape and matured.

Russia started waging information war on Ukraine in the first couple of years of national independence. It has never stopped, nowadays climaxing into actual hostilities on Ukrainian territory. The grief and tears of the mothers of the Heavenly Sotnia’s men, the profound shock suffered by the Ukrainian community after learning the true scope of corruptions on the upper echelons of power, reaching all the way down to local bureaucrats, judges, and prosecutors, were shortly followed by the annexation of Crimea, with attendant looting, murders and tortures to the accompaniment of Kremlin propaganda. Worst of all, there was that feeling of deep humiliation and shame, something Ukrainian politicians and the proverbial powers that be have been trying to make Ukrainians accept. What we can watch and hear these days reflects the realities of Russia’s information war against Ukraine.

Marking this anniversary [May 4. – Ed.] of the passing of my beloved husband, Dr. James Mace, I find myself trying to convey a message to him, with some of his questions answered; I keep studying his manuscripts and finding answers to some questions he raised. I keep watching our current political leadership, wondering when they lash out at each other, being broadcast, and then appear in various talk shows. I hope to God we made the right choice this time – I mean our candidates for the coming parliamentary elections. I do because there is no time for making another mistake. Now there is a people that has long moved far ahead of its political leadership in terms of self-development and national identity. I do hope that we can combine efforts and step over this pain threshold in Ukrainian history. I do because I believe that the Heavenly Sotnia’s men are watching from very high above, and that my beloved James is up there with them, still believing that after we learn the truth and make the right decision, we shall overcome one day, maybe sooner.