As I studied the history of Ukrainian special services, my attention was involuntarily drawn to a striking likeness between what happened in Crimea and eastern Ukraine and the events that occurred almost a hundred years ago.

The impression is that the Kremlin’s strategists and political scientists have dusted off the almost century-old plans of the first Bolshevik-Ukrainian or, as some historians call it, Soviet-Ukrainian war in 1917-18 and decided to apply them again against the freedom-loving and independent Ukrainian nation. The combination of the old well-tested and new methods has resulted in a so-called “hybrid” war. However, Putinists are rejecting the very idea of a war and want to convince everybody that it is a domestic conflict – exactly as it was almost a hundred years ago, when Ukrainian Bolsheviks confronted the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR) or the Ukrainian State under Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky.

As I read archival and historical research materials, I noticed some interesting parallels. I am not going to retell all the peripeteia of the 1917-21 Ukrainian Revolution, analyze the actions of the Central Rada, the Hetmanate, the UNR Directory, and their leaders, speak about territories and borders or the then status of Crimea, the Donetsk-Kryvy Rih and Odesa republics, Tauris, the Kuban People’s Republic, and other short-lived entities. I will only focus on the bright episodes that strikingly resemble today’s events, on the forms and methods of information warfare, and on special operations which the then special services – predecessors of Russia’s current FSB and GRU – carried out with the help of influence agents, the fifth column, and all kinds of marginalized people.

Let us first recall the events of the last months of 1917. In late October, Kyiv’s Central Rada adopted the 3rd Universal (decree) that proclaimed the Ukrainian National Republic which was in fact embarking on the road of building an independent state. Under this decree, the UNR was to comprise the Kyiv, Volyn, Podillia, Chernihiv, Poltava, Kharkiv, Katerynoslav, Kherson, and Tauric (without Crimea) guberniyas, while the destiny of Kursk, Kholm, Voronezh, and other regions, where Ukrainians constituted the majority, was to be decided by the local population itself.

This course of events did not suit the Bolshevik government in Moscow. They immediately began to draw up a plan to hinder the making of a sovereign Ukrainian state. The first attempt to dissolve the Central Rada in Kyiv on December 4, 1917, was thwarted. The All-Ukrainian Congress of the Councils of Workers, Soldiers, and Peasants’ Deputies failed to do so – allegedly for lacking a quorum. Then the Bolshevik delegates went to Kharkiv to make a second attempt. To support them, the first trains began to arrive from Russia on December 9. They carried Bolshevik troops and party propagandists “armed” with red flags, leaflets, and rhetoric about unity, the global revolution, land to peasants and factories to workers.

Does this not resemble the spring of 2014, when Kharkiv saw trainloads and busloads of thugs with Russian tricolors, who came to campaign for joining Russia, picket the regional council, and force councilors to vote for something? Moreover, the Kharkiv of 1917 looks more like the Sloviansk of 2014 except for the “little men” being red, not green, then.

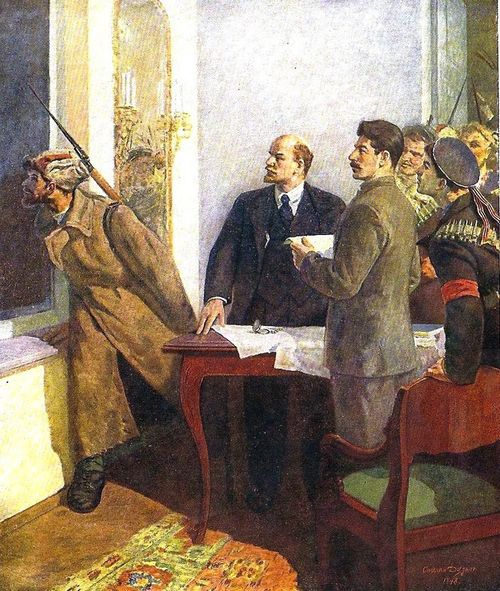

LENIN, STALIN, AND “REVOLUTIONARY SAILORS.” IN 1918-1920 THEY FLOODED UKRAINE WITH BLOOD TO FORCIBLY BRING IT BACK TO THE RED EMPIRE

In December 1917 the Bolsheviks, guarded by the Soviet troops, managed to hold an alternative congress of workers, soldiers, and peasants’ deputies in Kharkiv. To tell the truth, the 200 delegates represented as few as 89 out of Ukraine’s more than 300 councils. But this did not hinder proclaiming the establishment of Soviet power in the Ukrainian National Republic and forming a government and the armed formations which Moscow recognized and supported. The existence of two centers of power – in Kyiv and Kharkiv – made it possible for Russian Bolsheviks to formally stay out of the war and publicly present it as a domestic conflict.

Those were the events of the so-called first Soviet-Ukrainian war in 1917-18. The invasion of Ukraine was carried out by the Bolshevik “fifth column,” such as the Russified proletariat of big cities. This inevitably calls to mind certain analogies with the Donbas marginal people who are now fighting on the side of the self-proclaimed “DNR” and “LNR.” But what interests us more is the strategy and tactics of the Bolshevik offensive.

The second phase of the Soviet-Ukrainian war began when the UNR Directory came to power in December 1918 and declared that it represented the organized Ukrainian democracy and the entire active citizenship. Right after this, the Provisional Workers and Peasants’ Government of Ukraine was formed in Moscow and Red Army units with Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko at the head launched an offensive against Ukraine from Kursk without declaring war.

When these troops illegally invaded the Ukrainian territory, the UNR Directory sent a number of notes to Moscow. In response to this, Soviet Russia’s People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs, Georgy Chicherin, sent a radio-telegraphic message on January 6, 1919. The note was as much permeated with cynicism as are the present-day statements of the Russian foreign ministry about the absence of Russian troops in eastern Ukraine and noninterference into the internal affairs of Ukraine. Chicherin emphasized that the hostilities in Ukraine were between the troops of the Directory and what he called a thoroughly independent Soviet Ukrainian government. Commenting on the Directory’s aspiration to settle the conflict peacefully, he said that “it is a conflict between the Directory and the working masses of Ukraine which are striving for a Soviet setup. Accordingly, the conflict will be taking the shape of an armed struggle as long as the Directory applies to the Soviets the tactic of violent suppression of them.” Well, the current Russian foreign minister really has a role model.

Other leaders of Soviet Russia and the Russian Communist Party, such as Leon Trotsky and Grigory Zinoviev, did not resort to diplomatic niceties at all. Their public statements were full of undisguised hostile attitude to Ukraine’s sovereignty. As for the methods by which Moscow intended to tame Ukraine, they are also very much in line with those of today.

The main channels for subversive activities against the Ukrainian State in 1918 were ambassadorial and consular opportunities. Emissaries were sent, legally and illegally, through these channels to organize an anti-governmental underground. Flouting the norms of international law, Soviet Russia made active use of its delegation in peace negotiations with Ukraine. The delegation included people who had the experience of intelligence-gathering and subversive work in the tsarist army, while about 1,000 agents and propagandists were sent disguised as diplomats and consular staff, who were assigned the task of fomenting an anti-hetman uprising. Incidentally, Christian Rakovsky, the head of the Russian so-called Peace Delegation, was given about 40 million rubles for this purpose.

Illegal formations usually received funds from Russia by diplomatic mail. An apprehended Russian diplomatic courier was found to have three million rubles intended for subversive actions. Diplomats themselves were also ensnared at times by the security bodies of a young Ukrainian State. In the summer of 1918, the Soviet consul M. Bek and eight of his subordinates were arrested in Odesa. Searching the consulate, security men found a great deal of propagandistic literature, instructions for armed actions, and cards with the photographs and bio data of underground organizations’ members.

The Bolsheviks pinned great hopes on the communist underground in Ukraine’s working-class centers. There was a well-ramified network in the Donbas. Clandestine groups in Yuzivka, Mariupol, and Luhansk were assigned a task to spread political propaganda, organize strikes, commit sabotage, and form armed units for a future anti-hetman uprising. Safe houses were set up and funds were brought in for this purpose.

The same work was done in Katerynoslav, Odesa, Sevastopol, Simferopol, Kerch, and other cities, where a strike movement was unfurling under the guidance of communist activists. Do these events of the past not remind you of something? And the numerous acts of sabotage and terrorism? Let us recall just some of them. On June 6, 1918, an act of sabotage was committed in Zvirynets on the outskirts of Kyiv, which caused gunpowder stores to explode. This left more than 200 people dead, about 1,000 injured, and 10,000 homeless. On July 31, 1918, terrorists blew up a large ammunition store in Odesa.

Those were not isolated instances. Acts of sabotage were continuously committed against UNR troops on transportation and communication lines. Documents indicate that all the brigades, regiments, and special-purpose units of the Soviet insurgent forces in Left-Bank and south-eastern Right-Bank Ukraine were ordered to form “demolition teams” of 5 to 25 people each. These teams were supposed to destroy telephone and telegraph lines, bridges, attack headquarters and other military facilities. It is perhaps from that time that the present-day Russian GRU and FSB Special Operation Forces keep count of the time their special units were set up. But, what is more, they were and still are honing their skills on the Ukrainians.

The fighting capacity of the Hetmanate’s armed forces was also undermined by way of recruiting and winning over servicemen. It is noteworthy that Komandarm Sergey Kamenev visited Ukraine in June 1918 on the instructions of Leon Trotsky, the then People’s Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs of Soviet Russia, to win over air force pilots and technicians. The Bolshevik emissary tempted specialists with favorable conditions of service in the Red Army and better salaries. He flashed wads of 1,000-ruble bills and demanded that pilots ferry their airplanes to Russia.

The Central State Archive of Ukraine’s Top Bodies of Administration still keeps the materials that expose Kamenev’s subversive activities. He was placed under surveillance, which found out that he was secretly meeting air force officers in restaurants, cafes, and Kyiv streets. A forged ID of a First Ukrainian Aviation Unit officer was found during a search in his hotel room. Further operative actions disclosed that the Moscow visitor had managed to recruit a pilot, von Witte, who had a money receipt notice. After this the emissary and the agent were arrested and put to the Lukianivka jail.

Past year the Security Service of Ukraine also apprehended similar recruiters and their henchmen. The latter-day followers of Kamenev incited Ukrainian pilots to smuggle out up-to-date warplanes. They are now in jail, pending trial.

This kind of parallels occurs at almost every turn. For example, that-day documents and memoirs of the participants in revolutionary events recall contacts between Moscow Bolshevik functionaries and Donbas coalmine owners. Back in that time, Moscow used some Donetsk-based “oligarchs” for funding a network of Russian chauvinists’ armed formations that were supposed to stage an open revolt against the existing Ukrainian government. It is about, among other things, a secret organization in Kharkiv, which had an almost 1,000-strong battalion of officers, 3,000 rifles, and 20 machineguns. It was planned to begin the revolt when the Volunteer (White) Army launched an offensive against the Ukrainian State.

There are a lot of examples like this. Of course, there should be no simplistic comparisons, for the 1918 situation essentially differs from that of today. But this can even be of benefit to us. The strategy of dismembering Ukraine into all kinds of “DNR,” “LNR,” and “Novorossia” has already been tried out by the Bolsheviks before. Therefore, there are not so many changes in the current Kremlin politicians’ plans of conquest and rhetoric. Suffice it to recall Trotsky’s words in a secret instruction to communists that “there is no Russia without Ukraine. Russia cannot exist without Ukrainian coal, iron, ore, grain, fatback, and the Black Sea – it will choke without Ukraine, as will do Soviet power and we.” In this connection, to analyze the strategy of present-day Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, it is a good idea to look into the past strategies of the Bolshevik conquest of Ukraine.

What was going on in 1917-20 on the territory of Ukraine is now evident, one way or another, in the Donbas – albeit in a horrible, incomprehensible, and hypertrophied manner. It looks like some parallel worlds or documentary films – an old black-and-white and a modern colored one – are overlapping each other, which makes you feel terrified because you are aware that this has already happened to us before but no lessons have been learned. Instead, some may have developed certain immunity against that old infection and were thus unable to see through a new threat. This further proves the importance of knowing and understanding history and learning on past mistakes so that we do not repeat them over and over again at the cost of human lives, values, and territories.

What adds some optimism in this situation is the fact that we, the nation, have become different over the years and decades we have lived, particularly in the past year. Irreversibly departing from the Bolshevik, Soviet, communist past, we are unceasingly approaching other ideals and values. And I am sure this deja vu effect will never come back.

Oleksandr Skrypnyk is an advisor to the chief of Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service, a researcher in the history of Ukrainian special services