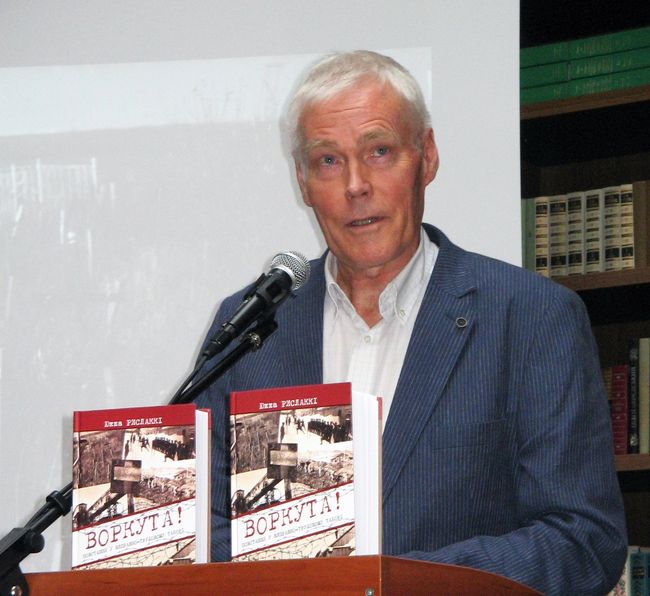

At a recent Publishers’ Forum in Lviv a Ukrainian version of Jukka Rislakki’s book Vorkuta! GULAG Uprising, won an acknowledgement award of the Publishers’ Guild. The author is a Finnish journalist, non-fiction writer, political cartoonist. He was a guest of honor at the forum.

LEARNING ABOUT UKRAINIANS IN THE COURSE OF RESEARCH

Jukka Rislakki was born in 1945, in Kuusankoski, Finland. He has lived in Latvia for the past 20 years. He worked for the prestigious Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat for more than 30 years, writing on history, pop culture, and ideology in the Baltic States. His wife is Anna Zigure, writer, translator, former Latvian ambassador to Finland and Estonia. In 2007, his best known analytical work on Latvia came off the presses in Finnish, then in English (“The Case for Latvia. Disinformation Campaign against a Small Nation”). He was awarded the Cross of Recognition in Riga on May 4, 2009, the day of restoration of independence of the Republic of Latvia, in recognition of his meritorious contribution to the international image of the republic.

Jukka Rislakki’s book on the Vorkuta prison camp uprising is the first non-fiction publication dedicated to one of the biggest GULAG revolts. During the book launch ceremony in Lviv, Mykhailo Komarnytsky, founder and CEO of the Litopys Publishing House, noted that he had decided to publish a Ukrainian version of the book as a tribute to his father who had taken part in the Vorkuta uprising in 1953. Among those present were the sons of Yosyp Ripetsky from Ivano-Frankivsk oblast, one of the characters in the book who had died in October 2013. Volodymyr Viatrovych, head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, took the floor to emphasize the special meaning of Rislakki’s book in revealing little-known pages in history. Taras Vozniak, chief editor of the Yi magazine, noted that Ukraine regrettably lacks scholarly research relating to Ukrainians who took part in the GULAG uprisings.

The Ukrainian translation was done by Yurii Zub of Lviv, currently a postgraduate student at the University of Helsinki, author of a Finnish-Ukrainian idiomatic dictionary. In fact, Jukka Rislakki said that the Ukrainian version sounds even better than the original.

Indeed, this non-fiction work is easy to read and is best described as a page-turner, even though the topic is markedly tragic. Rislakki’s book is about one of the biggest GUGAL uprisings, based on interviews with eyewitnesses and research papers that few Ukrainian historians have had access to.

“Ukrainians and people from the Baltic States proved the most active participants in the uprising in the summer of 1953, after Stalin’s death, who paid a dear price for their resistance. I started working on the book ten years ago. I decided to write about a Finn who died during the revolt. As I worked on the book, I changed my mind and decided to write about all who took part in it. I learned a lot of new facts about the Ukrainians, that they constituted the majority of the GULAG inmates, that they were always the most active rebels among the GULAG inmates of various ethnic origins, with the Poles coming next,” said Jukka Rislakki.

In his book one can learn from the story of the Finnish rebel, Eino Prukja, about Soviet repressions against the Finnish people. Such information is scarce in Ukraine, although we know that there were repressions. Reading about the uprooting of all that was Finnish in Karelia, about Finns being arrested in St. Petersburg simply because they are Finns, one immediately recognizes the same Soviet modus operandi in Ukraine, in the deportation of Crimean Tatars.

VORKUTA UPRISING

There are numerous revolts in GULAG history. They varied in scale but had the same outcome: ruthless suppression. Three of them – in Norilsk, Vorkuta, and Kengir – proved the best organized and worst ones for the authorities, so that in the end it was decided to change the system of incarceration, revise some cases, and release a number of political prisoners. The new inmates served their terms under different conditions in 1960s-1970s, they could continue their resistance as human rights champions rather than armed rebels.

There is more or less sufficient media coverage of the Norilsk and Kengir uprisings. The one in Vorkuta remains to be researched. The Ukrainians who were the most active participants have left little in print. The most important aspect of that revolt was that the inmates serving the longest terms, being treated the worst by camp authorities, demanded freedom rather than better working conditions. Moscow law-enforcement documents described the event at the time as “organized counterrevolutionary, anti-Soviet sabotage.” The political prisoners knew that the totalitarian authorities would punish them severely, but they refused to die as slaves. “Proud Ukrainians formed a solid team in the Vorkuta GULAG camp, they wholeheartedly hated the Soviet system; their patriotism and spiritual fortitude were amazing,” writes Jukka Rislakki.

The uprising at maximum security Camp No.6 (known as RechLag or River Camp) at Vorkuta lasted from July 19 until August 1, 1953. The camp consisted of 17 zones with a total of 38,589 inmates, including 16,812 nationalists (10,495 Ukrainians, 2,935 Lithuanians, 1,521 Estonians, 1,075 Latvians, and 510 Poles). As political prisoners, they were exempt from amnesty after Stalin’s death.

The revolt plan was carried out step by step, first as a number of strikes, on an almost daily basis, here and there in the prison camp. There were underground groups in RechLag, organized on an ethnic or community basis. The rebels had their headquarters tasked with monitoring stoolies, NKVD operatives, and camp administration. The HQ “officers” were not on the camp work team lists. Barracks No. 42 accommodated the “Bandera Headquarters.” Among the most active Ukrainian participants in the rebellion conspiracy were Yurii Levando, Fedir Volkov, Edward Buts, OUN UPA members Serhii Kolesnykov, Vasyl Hryhorchuk, Yosyp Ripetsky, Vasyl Zaiets, Petro Sobchyshyn, and Volodymyr Maliushenko. Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, and Germans had their own headquarters. In Zone Two, the Polish inmates were led by Kedzierski, ex-captain of the Polish army.

On July 19, 350 inmates who had been transferred to RechLag from StepLag (Steppe Camp) in Kazakhstan and placed in another zone, refused to report for work. They demanded that the authorities abolish maximum security corrective labor camps under the interior ministry’s jurisdiction, penal servitude, and shorter terms under Article 58 of the Soviet Criminal Code [arrest and trial on charges of anti-Soviet activities as an “enemy of the people”], that no inmates be transferred to other camps before the visit of the communist party central committee’s official. The statement was signed by some 150 inmates. On July 22, as many as 1,500 inmates of Zone Two refused to report for work on first and second shift at Coal Mine No. 7. The next day there were 3,000 inmates on strike in that zone.

The camp administration promised better working conditions (9-hour working day), that the ID numbers would be removed from their clothes. Now every inmate was to be addressed by first name and patronymic. They could write a letter a month rather than two letters a year, send money to their families, draw up to 300 rubles from the savings bank account each month. They were allowed visits by family members. An announcement to this effect was immediately made in the RechLag rebellious zones.

WESTERN UKRAINIAN INMATES, EX-OUN MEMBERS, ARE TREATING THE ORDER NEGATIVELY

Ukrainian nationalists launched an active propaganda campaign against reporting for work. They said it was necessary to make the authorities comply with all the inmates’ demands. There are archival documents with stoolies and operatives’ secret reports. They read, in part: “Western Ukrainian inmates, ex-OUN members, are treating the [camp administration’s] order negatively, saying the inmates have to refuse to report for work en masse and thus win substantial concessions, like shorter terms, [work quota] offsets, barracks doors unlocked… Western Ukrainian Banderaites are expressly dissatisfied. They say the privileges [granted the inmates] are miserable pittance given only once, so as to assuage the rebellious moods among the inmates.” The Ukrainians were actively supported by Germans and inmates from the Baltic States. Inmates in Zones Two, Three, and Sixteen showed a negative attitude to the privileges. A total of 8,700 inmates refused to report for work, stopping Coal Mines Nos. 7, 12, 14, and 16, as well as TETs-2 [Thermal Power Station No. 2]. On July 24, inmates in Zone Sixteen refused to report for work, so there was no night shift. On July 25, 400 inmates on first shift at Coal Mine No. 29 in Zone Ten joined the strike (Ukrainians had an underground organization that was getting prepared for the rebellion). Political prisoners unfurled red banners with black bands that served as symbols of struggle, similar to those practiced by the nationalists.

On July 26, the camp administration transferred 52 active anti-Soviet inmates from Zone Ten to a separate camp, OLP No.62. That same day 16 Ukrainian nationalist leaders were locked up in Zone Fifteen. Zone Three inmates retaliated by attacking the SHIZO penal isolator, freeing 77 active rebels. The camp guards opened fire, killing two inmates and wounding as many. On July 27, the camp administration tried to get all rations out of Zone Ten, but more than 300 inmates offered resistance, so no food was taken away. During the night of July 28-29, another 21 rebellious inmates from Zone Seventeen were isolated and transferred to a different zone.

The inmates’ strike was turning into a full-scale rebellion. On the morning of July 28, inmates in Zone Thirteen (Coal Mine No. 30) refused to report for work after learning that work at the neighboring mines had stopped. On July 29, some 12,000 inmates in camp sections Nos. 2, 3, 10, 13, and 16 refused to report for work. Half the RechLag inmates were now in revolt, including 15,604 inmates in seventeen zones. The rebellion was coordinated by an underground center made up of inmates representing each camp section/zone, but mostly of Ukrainian and Baltic nationalists. On July 29, the rebels held talks with a commission from the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR, led by Deputy Interior Ministry General of the Army Ivan Maslennikov, but to no avail. The Soviet authorities worked out Plans A, B, and C to suppress the revolt.

RETALIATION

On July 31, 1953, the guards of Zone Two received reinforcements. The rebellious inmates were surrounded, divided into groups of 100 and herded outside the zone. The operation to suppress the revolt began on August 1, in the most rebellious tenth zone of the prison camp. Roman Rudenko, Prosecutor General of the USSR, arrived to have first-hand information. He personally shot one of the revolt organizers, a Pole known as Viktor Ignatowicz, in front of the inmates lined up at Coal Mine No. 29. After that prison camp guards opened fire. The inmates offered resistance. They began by blocking the entrance gate with 350-400 men gathered 50 meters from the gate. Camp authorities dispatched 50 camp guards to the zone. They charged and the rebellious inmates resisted, trying to get out of the zone. Shots were fired, but access to the gate was blocked by army officers and armed guards who also opened fire.

In the end 53 political prisoners (including 30 Ukrainian OUN UPA members) were killed and 138 wounded. After the punitive operation, 11 inmates were locked up in Zone Ten, 40 received terms of penal servitude, and 206 were transferred to OLP No. 43 on general terms. A total of 1,122 inmates were sent to the penal isolator as active rebels, with 15 grabbed immediately and another 14 apprehended later; 250 inmates received one year maximum security prison term.

After the punitive operation, the inmates of Zone Two and Zone Ten in camps Nos. 3, 4, 13, and 16 were read Order No. 105 of July 30, 1953, whereby they could keep the barracks doors open round the clock, with the bars removed from the windows, with workday quota offsets for the RechLag inmates. They were told that their complaints filed with the interior ministry’s commission, dated July 31 and August 1, would be duly processed. In view of these promises, rumors about mass shootings of rebellious inmates, the bitter experience in Zone Two and Zone Ten revolts, the inmates gave up struggle and reported for work. The surviving rebellion organizers were arrested, stood trial on December 25, 1953, and received additional terms. The dead rebels were secretly buried on the side of the road by the pit refuse heap near Coal Mine No. 29 (on August 1, 1995, a memorial dedicated to the victims was unveiled at the Yurshor Cemetery).

The Vorkuta prison camp revolt was suppressed, but the inmates had achieved certain results, making life for other political prisoners easier. Many of the latter were released, beginning in 1956, after their cases were revised [during the Khrushchev Thaw campaign]. However, underground organizing activities continued, resulting in another major prison camp uprising at Kengir in May-June 1954.

***

“In Vorkuta and other GULAG camps, Baltic and Ukrainian inmates were numerically predominant after the World War Two. The irony of history is that their peoples are being currently threatened and pressured by Putin’s Russia in the first place,” Jukka Rislakki writes in his Vorkuta book.

Russia is concealing the truth about the Soviet totalitarian regime from its citizens, and that regime is quickly returning. Unlawful arrests are taking place and people are being abducted. The courts are handing down sentences based on political charges, and people are serving out their terms in the very same places where prisoners of the GULAG served out their sentences under the Soviets. Swedish historian Hans-Goeran Karlsson believes the trauma is not limited to the generation that suffered it. The questions of repentance, responsibility, and punishment are not exhausted with the passing of the generation that begot the perpetrators of these repressions.