DNIPROPETROVSK – The Dnipropetrovsk Alfred Nobel University of Economics and Law with the participation of PEN International members from Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania and Belarus held the discussion: “Celsaw Milosz and the intellectual elite of the postwar Central and Eastern Europe: the ‘captive mind’ and the change of intellectuals’ roles.” It was organized within the framework of the project “Milosz’s lessons for Ukraine” with the assistance of the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, Polish Institute in Kyiv and the Book Institute. Thus our country has joined the events dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the prominent philosopher and poet, Nobel Prize laureate in whose honor the current year is called Milosz’s Year in Poland. The first international discussion of the project took place back on September 17 in Lviv during the Publishers’ Forum. The place for the second one was not chosen accidentally either. The Dnipropetrovsk Alfred Nobel University of Economics and Law systematically develops the Nobel movement in Ukraine. Besides, this university traditionally has strong scientific and business ties with our Polish neighbors. When opening the discussion, chancellor Borys Kholod emphasized that philosopher and poet Ceslaw Milosz “devoted his life to the better understanding between the people.” This idea was repeated by the roundtables participants: Polish translator and literary critic Adam Pomorski, Lithuanian prose and drama writer Herkus Kuncius, Belarusian poet and translator Andrei Khadanovich and Ukrainian publicist and publisher Andrii Pavlyshyn. The discussion was moderated by the historian from Lviv Yaroslav Hrytsak.

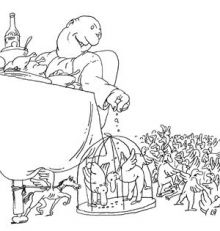

The discussion did not touch upon Milosz’s poetry that much but his book The Captive Mind in which the author had presented his reflections about intellectuals’ moral choice after his escape from Communist Poland. After the war a participant of the antifascist Resistance movement Milosz collaborated with the pro-Stalin regime and even did his diplomatic service in New-York and Paris as the Polish ambassador. In 1951 he did not come back from his foreign mission and, hiding from the secret services, wrote a book that later became the manifest of Polish dissidents and Solidarity movement activists. “This book is not that simple,” Pomorski remarked, “Milosz had been a leftist since the prewar time but when he faced the reality of postwar Poland his views changed.”

It would be recalled that according to the Yalta Agreement, the Polish borders were moved to the West, its territory decreased by a third and the country became monoethnic without any Jewish, Lithuanians, Ukrainians or Germans. As the poet who spoke several languages figuratively said, Poland “got deserted.” However, the totalitarian regime caused yet more changes: the Polish intellectuals had to adapt “temped by the material benefits.” Many Polish intellectuals “put on masks” that often “adhered to their faces,” Pomorski said.

For another discussion participant Herkus Kuncius the creative work of Milosz, born in Lithuania, is valuable because it is multicultural. “I compared that the Lithuanian intellectuals have traveled the same path,” he said. “Before the war there were Lithuanian authors who glorified Stalin but many of them finished their lives tragically. Their works are included into literature books and studied at schools and institutions of higher education. We can see something similar in Milosz’s life and creative work.” The guest form Lithuania saw the parallels with their communist past but the poet and translator from Belarus Andrei Khadanovich recognizes them in the present. “I cannot tell that I came from the free country,” he openly said. “Belarus is still a totalitarian country where there are ‘black lists,’ where politicians and writers are in prisons and where the phenomenon of ‘creeping conformism’ exists. Khadanovich reflects about what is happening in the heads of the modern intelligentsia and students that silently accept the events happening in their country. “Sometimes even the Europeans ask why we do not like Lukashenko since he resists the chaos,” he said. The poet considers The Captive Mind written half a century ago to be a book “topical for the Belarusians.”

However, this book is obviously topical not only for Belarus. As the Ukrainian participant of the discussion Andrii Pavlyshyn who had headed Amnesty International Ukraine remarked the “Ukrainian intellectuals need Milosz’s book a lot”. The fragments of The Captive Mind were published for the first time during the period of perestroika in Vselennaya revue. However, now it is difficult to find this book in Ukrainian. Touching upon the topic of conformism among the intellectuals, Pavlyshyn remarked that during the years of independence many former communists became nationalists and they are able to “evolve.” “Most people want to be conformists, it is not a purely Belarusian or Ukrainian phenomenon,” he stated. “Today we are ready to exchange freedom for stability. It does not depend on ideology but the human material we are made of.” It is symbolic that the Belarusian poet Khadanovich gave the Dnipropetrovsk writers a couple of books by Milosz whose numerous works have already been translated into Belarusian. Probably, the Ukrainian intellectuals and publishers will have to do this job in the nearest future.