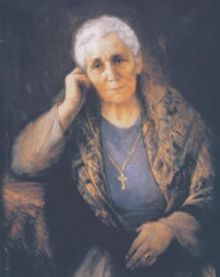

Maria Melnyk was born on Dec. 4, 1920. She and her husband lived under the surveillance of the Polish and later German police. In 1941, he was arrested by the Germans on charges of collaboration with the UPA. Followed three months spent in Majdanek. Later they resettled in Volodymyr-Volynsky (the Kholm region) and lived in someone else’s home. Her husband, a Greek Catholic parish priest, remained true to his faith and cloth, hence the KGB surveillance that lasted almost until the 1990s. He died in a hospital for no obvious reason. Their home was repeatedly searched, they were branded as Banderites and Uniates, and their acquaintances kept their distance. Despite all this, Maria raised 12 children in a true patriotic spirit, seeing that they receive a musical and post-secondary medical education. She taught them to sing Ukraine Is Not Yet Dead… Verily, some people don’t realize what they are capable of.

Maria Melnyk’s third daughter, Yaroslava, brought the Editors a list of her five brothers and six sisters together with their families. Here is an entry: “3. Yaroslava: 2 children: Natalia (3 grandchildren) and Olenka (2 grandchildren). Yaroslava is a pharmacist; Natalia, Olenka, and Oleh are dentists.” Or another one: “7. Volodymyr: 2 children: Solomia and Taras. Volodymyr is a dentist, Solomia is in her fifth year at Lviv Medical University, majoring in dentistry; Taras in his 4th year (dentistry).”

None of Maria’s 12 children has more than five of his/her own, perhaps because they never had a true childhood. However, there was always a sense of responsibility for each other. In fact, only Natalia, Maria’s ninth child, has five children, two of whom are also dentists. Her youngest daughter, Mariika (neurologist by training), has seven children, three of her own and four of her Canadian husband (she started as their nanny in Canada to earn money for an apartment in Kyiv).

Reading this list and trying to picture everyone on it makes your head spin. Just imagine remembering all their dates of birth, wedding anniversaries, let alone those of brothers, sisters, and their children! All of Maria’s children keep a sensitive finger on the pulse of family affairs, they share each other’s joys and sorrows. People raised in large families appear to have a different worldview; each of them can count on others’ help, support, and advice. Having so many brothers and sisters is a rare experience, indeed,

Maria and Ivan Melnyk’s three-generation family tree is as follows: 12 children, 23 grandchildren, and 17 great grandchildren. In terms of training and occupation, there are 22 dentists, two pharmacists, two lawyers, and two students of medical school.

Momma Maria couldn’t work, of course, and it is easy to guess that her husband, Ivan Melnyk, worked as a dentist. For his children and grandchildren he was always the highest moral and professional authority. Maria’s daughter Yaroslava says her younger daughter Olenka, despite her talent for philology at school, neverthelss insisted, “I’ll be a dentist, like grandpa. Am I any worse than the rest?”

Ivan Melnyk, however, gave his offspring more than just a path for professional development. He provided them with an example of personal moral fortitude. He and Maria were tempered by hard life and raised their children as highly cultured and faithful individuals. Maria would wait for her husband’s release from Polish jail and helped him with his medical practice (the Melnyks were allowed to run a small private clinic), just as she would later wait for him to return from yet another KGB “interview” in the middle of the night.

Maria could not imagine raising her children in anything but a patriotic spirit. In the 1940s, after moving from the Kholm region to Volodymyr-Volynsky (she still lives there), regardless of who was in power, she taught her children to sing “We were born in the blood of the people/Cradled in harsh prisons/We stood on guard in battles for freedom/And hatred of dishonor and the yoke.” Or Ivan Franko’s “No longer, no longer should we/The Russian or Pole meekly serve!/Ukraine’s ancient grievances lie in the past —/Ukraine doth our whole life deserve.” She did this in the 1960s and 1970s. Small wonder that in 1991 Yaroslava Melnyk, student of Kyiv’s Ukrainian-English School No. 190, should start singing Ukraine Is Not Yet Dead… when the teacher asked if any of their grandparents knew the lyrics of the anthem (she didn’t even ask if their parents did).

Also, all of the Melnyks’ children are music school graduates; they can play the piano, violin, double bass, and button accordion. Such was their childhood: tight daily schedule, with several options: help daddy (they had a miniature farming plots with beehives), do your homework, or practice music. The family never prospered: younger children inherited their older siblings’ clothes, and the elder ones spent several years in boarding schools as this guaranteed regular meals. Children were born every one or two years. The eldest daughter, Liubomyra, was born in 1941.

The big family lived in inner emigration, concealing embroidered tryzub emblems, sharing stories about the UPA, Katyn, secretly listening to Radio Liberty. Maria Melnyk inherited her patriotic spirit from her father, a parish priest who subscribed to the Ukrainian newspaper Narodna volia. He was known as a trustworthy man and he maintained contacts with Ukrainian nationalist organizations.

For the Melnyks, the 1960s to 1970s marked a period of living “by the book.” Ivan Melnyk was immersed in his work night and day. There is a favorite family story. Maria learned that her fourth child, her son Roman, was going to serve in the army (he was studying in Belarus at the time). Her husband was in Kyiv. He returned at night, so Maria didn’t want to upset him and decided to share the bad news in the morning. During the night, however, he was called to see a patient. She tried to explain that the man was too tired, but Ivan heard her and got mad. “Can’t you understand that someone’s suffering? How can you say no?” He left home in a rush. Maria then told him about Roman. Ivan packed and left for Belarus immediately. He was such a man. He never spared himself.

The Melnyks probably wouldn’t have had to face so many challenges but for Ivan being ordained as a Ukrainian Greek Catholic priest. His parents had sent their only teenaged son to receive an education at a monastery in Buchach (currently in Ternopil oblast). Since then the boy had dreamed of becoming a priest. When he was a young fellow his parents forbade this because he was their only son. In 1977, his dream came true. Since then Ivan would conduct a daily service at home, so that everybody in the family had to get up at six in the morning and offer up a prayer in the home church. His children recall that he conducted services in Kyiv churches. Needless to say, the Soviet authorities took a dim view of the Melnyks, considering that the family refused to meet them halfway.

And then Rev. Ivan made a decision that was fateful for the family. He made up his mind to attend a funeral in the town of Stryi. It was the funeral of his good old friend Bishop Iosafat Fedoryk, who was the Melnyks’ moral authority. From that time on the family was under constant, practically undisguised KGB surveillance. They remember seeing someone walk up and down the street past their home and in the morning they would find multiple footprints on the ground under the big lilac bush facing the house. Their home was often searched; they seemed to be looking for gold or hard currency.

The worst had come to worst in 1981. By that time half the children had their own families and all their homes were searched at the same time. Yaroslava (she was then living in Kyiv with her husband and two daughters) recalls:

“The search began at four in the morning and lasted half The Day. Our home was a shambles. My husband and I were forbidden to go to work or even leave the house. They ordered the eldest daughter to take the youngest one to The Daycare center… They took me to a militia precinct, locked me in an empty room, and left me there for several hours. Then they let me go. I found my husband and children worried sick. In the evening we couldn’t get in touch with any of our relatives because the telephone line was dead. My sister got through to me only the following morning. She said her home was searched, literally turned inside out. Our father was taken to the polyclinic (at the time he was also in charge of a dental polyclinic. — Author) and the premises were also searched. He had a heart attack and was taken to a hospital…”

The young woman is pained to remember the tragedy. Two months after the heart attack their father got better and he was scheduled to be released from the hospital when he suddenly died.

“After Ukraine became independent my sister was visited by her former schoolmate. His father happened to be in the same ward with my father back in 1981. On his deathbed he asked to beg the Melnyks to forgive him. During the night when Rev. Ivan died he woke at the sound of a water glass crashing on the floor and then Rev. Ivan shouted, ‘What are you doing? Three of my daughters are only students!’”

The Melnyks are convinced that their father died a violent death.

In fact, all family members suffered [under the Soviets]. Yaroslava’s husband was prevented from defending his Ph.D. thesis. “You should at least speak Russian with Yaroslava over the phone. Don’t you know that she’s a Banderite?” they told him.

However, tragedies didn’t break Maria Melnyk but made her stronger. The woman didn’t break down after the death of her husband and three sons. She believes in God and her children. What more does one need to continue to live? “The children must complete their study,” Maria kept telling herself and kept working and looking after them. It was thanks to her that Liubomyra, Orest, and Yaroslava could graduate from Lviv Medical Institute; Volodymyr and Iryna, from that of Kyiv; Natalia and Mykhailo, from that of Odesa; Yevhen, from that of Poltava; Oksana and Zhanna, from that of Kharkiv; Roman, from that of Grodno in Belarus; Mariika, from that of Voroshilovgrad. The children tried to enroll in places where their family background was unknown. When some of them tried to apply for enrollment in Lviv, the local KGB simply told them to forget it.

A story about the Melnyks, about Momma Maria, is inseparable from the destiny of Ukraine. How happy they — and especially Momma Maria — were to greet Ukrainian independence. Now they were free to go to the Greek Catholic church! They forgave all those who several years ago would cross the street on seeing them, those who wrote about them as Uniates and enemies, those who spied on them and sent reports to the authorities. Momma Maria is still closely following political events, taking part in the elections, painfully watching what is happening in Ukraine. She was so happy when Yushchenko won the campaign. Now, as all the Melnyks, she is worried about the future. The children even try to keep the television off and avoid discussing political topics when Momma is present.

Red-letter days are the Melnyks’ favorite occasions, with over 50 persons gathering in Momma’s home. Traditionally, they gather to pray and sing songs. Momma remains their best advisor. She taught her children that everyone has three mothers: the one that gave you birth, your Motherland, and the Mother of God. Momma Maria has offered up prayers to the Blessed Virgin all her life (incidentally, the woman was born on December 4 when the faithful pay homage to the Mother of God).

In fact, she still summons her family in early December every year with precisely this in mind. God bless!