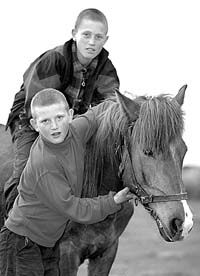

Already tending a horse, two pigs, hens, rabbits, and a garden plot, Yurko and Sasha now want to purchase a cow to have their own milk. The two boys, aged fifteen and eleven, toil to make ends meet and do not want to be taken to a boarding school.

Their house on the outskirts of a small hamlet badly lacks the touch of a woman’s hand. Against the background of the neat neighbors’ houses with bee-gardens and greenhouses, their house looks orphaned. Yet, in other respects their household is no different from those of their neighbors. The boys have stored as much firewood for the winter, chopped and arranged neatly against the wall. Like their neighbors, they have plowed their land plot and sowed barley, Sashko the younger leading the horse and Yurko steering the plow.

These children, whose childhood ended so early, seem to have no problems. They wash their own linen and clothes, with the younger brother acting as the family cook, for there is nothing difficult about it, according to Sashko. “You just throw in meat, cereals, and potatoes and let them boil for some time. Or better still, you just cook potatoes in their skins,” Yurko offered his simple recipe. Like everybody else in the village, the boys had fresh meat for Easter. They had one of their pigs slaughtered, and their aunt cooked some tinned stew. Their household is in perfect order. The older master has already mowed some hay for their mare by the name of Aliona and for the future cow. The numerous rabbits, hens, and pigs are not hungry either. Moreover, the boys even attend school.

When listening to all this you cannot shake the impression of being in some surreal world. It is just that it is not normal for these boys, although no strangers to hard work, to be so preoccupied with adult problems.

The boys last saw their mother, whom Yurko calls Lesia Mykhailivna Chul, seven years ago, when they were four and eight years old respectively.

“People say she has remarried and lives in the village of Sekun, Starovyzhiv district, and has a child,” Yurko repeated the word child several times as if wondering who they are for their mother.

“Their mother moved here from Zakarpattia and married at a very young age. They were well off at first, not loath to do any kind of hard labor. But alcohol ruined their lives. To sustain their drinking habits, they began pushing light drugs. When Lesia got caught, her husband shouldered all the blame so that the mother could remain with the children. While he was in jail, she began to lead an erratic life, was deprived of her parental rights, and left these parts. The father has returned home with tuberculosis, but has not changed his drinking habits,” village council head Tamara Tsiura described the tragedy of the boys’ hapless family.

In fact, the boys were raised by their grandparents. When asked who would milk the cow that they are expecting to receive any day now from Kovel District State Administration Chairman Vitaly Karpiuk, Yurko answered, “But Sashko will! He milked cows when the granny was still alive, because she was too old for this chore. Unfortunately, that cow wasted away, but we sold it for 130 hryvnias, added some more money, and bought a mare.”

This past February, the grandfather died on the fortieth day after the granny’s passing. Village and district officials immediately came knocking on the door offering to take the boys to a boarding school. “But where will we return to?” asks Yurko, fearing lest his father should sell the house in one of his drunken binges.

Now that they are waiting for their own cow, they are tending the village herd. Older Yurko can be hardly seen behind the well-fed cattle of the neighbors. Will the brothers cope with the constant pressure of village chores, which whole families can barely handle?

“They sure will. They have grown up toiling,” Aunt Onysiya states calmly. Now she is the main guardian of the orphans, whose parents are still alive.

“We must take care of them, because the children are not to blame for what their parents have done. As yet nobody has ever refused to help them,” says the village council head.

When we were saying goodbye to the young masters, a man bumped into us in the street and began complaining that the officials only profess to be taking care of the people.

“Our mother has raised nine children, of whom seven are still alive. She is 86 and ailing. Medicines cost a monthly 190 hryvnias. Once in twenty years I appealed for help to the district authorities, and received a mere fifty hryvnias!” the working-age man continued his diatribe.

“So the seven of you cannot support your mother?” the village council head retorted calmly. “But you know yourself that a house burned down in the village, and the district authorities had to provide relief money, and now they plan to buy a cow for the boys. Meanwhile, the annual budget of the village council is a mere 600 hryvnias. How much can we possibly give you?”

“So why don’t they stop saying that they are helping people,” the man would not calm down.

This encounter in the village street opposite the shabby house of the orphans waiting for their aunt from Rivne to come and paint it seemed symbolic and not accidental, being graphic evidence of the boys’ ability to endure the hardships and survive.