Any reform to be undertaken during the electoral race is liable to look populist, because this time is when outrages are revealed and urgent questions raised that politicians are trying to answer during the campaign rather than solve them during their term in office. They always found reasons not to do it then, but all obstacles go away as soon as they need to declare good intentions and call for changes to accumulate electoral support. It has become routine to have noisy shouting dominating at the time when they need to attract attention, and not change anything of substance. It is clear that the reform of the MIA, known to the public by negative associations and ugly definition, has long been urgent. We have learned, though, that even the word “reform” in this country means something superficial, non-systematic. After all, one can change the agency’s name, reassign officials or even fire them, but how can one squeeze out of them the genes of bribery, nepotism, abuse of position, etc.? A country that does not want to give up its vicious essence still wants to have a new face.

The MIA declares that its aim is to change the essence of the system, transforming it from one defined by the motto “to punish and collect rents” to a system dedicated to “serving and protecting.” The declaration looks like yet another faulty political message to the public, which already had heard too many of them during the presidential race with its primitive slogans. When asked about what kind of emotional response is brought about by this four-word formula, most respondents ironically frowned and ascribed them solely to the political component, and not to changes in the militia-public relationship, the former standing to be renamed as police for some reason. Changing the name in this case is explained by the need to rid the country of a relic of the Soviet era. When Vladimir Putin renamed his militia to police, people, disregarding all explanations, associated this change with historical experience, that is, with the tsarist government’s law enforcement rather than with the world standard. It seems that renaming in Ukraine should call to mind European associations and, therefore, tortures, including those known as “elephant” and “swallow,” should ostensibly go away with the word “militia.” Let us recall that these fairytalish animal names have far sadder meanings in the context of law enforcement in Ukraine, denoting ways of forcing a suspect to admit his “guilt.”

Draft of the MIA reform was created back in May, calling for radical changes in the structure of law-enforcement agencies. The drafting involved the relevant expert group headed by Yevhen Zakharov, but the draft became a talking point only lately, with the start of the electoral campaign. Minister of Internal Affairs of Ukraine Arsen Avakov published on September 18 a short video presentation of the reform on the official website of the ministry, dealing with the development strategy for its agencies, reform concept for the MIA, and detailed proposals in the relevant areas. The minister urged the public to participate in the discussion of this reform. We see already that it will be limited to a massive retrenchment and a clearer division of functions. In particular, the MIA’s subordinate bodies should be reformed into six police services: local, administrative, criminal, fiscal, military, and border ones. The draft stipulates that the MIA should ensure execution of public policy in the areas of law enforcement, the protection of the constitutional order and territorial defense, migration activities, border protection, civil defense and fire and rescue services. The minister should remain as a political figure, so that their change would not affect the heads of law-enforcement agencies. The latter’s professional segment should be based on the National Guard (a military formation), national police, border guards, immigration and emergency services. The highway patrol, which will be combined with the regular patrol service, will lose its functions of registrating vehicles and issuing driving licenses, and focus only on patrolling the national highways. A separate issue is introduction of technical means of verification of compliance with traffic rules that should prevent corruption on the road. Municipal police will be created in local communities, subordinated both to local authorities and the ministry, with its powers limited to the control of law and order in the streets and control of public welfare.

Following sectors of the police stand to get retrenched and reorganized: the General Directorate for Combating Organized Crime (GDCOC), transportation police and veterinary police. The GDCOC’s fate is particularly noteworthy. Famous for its part in combating criminals in the 1990s, it has personal and organizational experience of eliminating highly dangerous elements. Its reform, in fact liquidation, was discussed long before the Euromaidan. The GDCOC has special units at its disposal, which were not included into Avakov’s proposal apparently accidentally. Namely the legendary Sokil unit which, in particular, distinguished itself by arresting and killing notorious crime bosses.

The draft reform envisages the elimination of all special units (all included in Avakov’s proposal). The public associates their names not only with the protection of law and order, but more with execution of special missions, eventually turned into verbal irritants for the society. For example, the infamous Berkut riot police became such an irritant, which, as we are assured by some politicians, had no right to exist at all, because it was not acting under any law. These special forces will be replaced with a sole universal rapid response unit. The reform of the MIA also declared mandatory re-certification of police officers and attempted to introduce vectors of democratic control over the latter. Of course, qualitative changes can be easily shaded by shuffling old cadres in the place, if no fundamental replacement occurs. After all, the public expects mass personal changes in the MIA rather than just retrenchments.

The main problem of all reforms that anyone tried to introduce in our country was that they touched the form, not substance. Cleaning the river does not change the channel. The fact that the militia is to be renamed the police hints at window-dressing, appealing to psychological reflections rather than the underlying conclusions in the society. Another change of names comes. The public likes novelty? It will get police instead of militia. Does it matter how this or that copper calls himself?

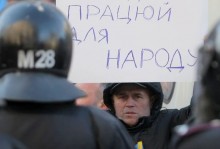

Photo by Borys KORPUSENKO

Downsizing (the main message of this reform as declared) is totally unrelated to fundamental changes. Retrenchments in the MIA are, of course, necessary, but not sufficient. This retrenchment in any case will involve even those police officers who have left Ukraine’s anti-terrorist operation (ATO) area, or moved to Crimea, or intentionally stayed in areas controlled by the militants. Orders to withdraw police from the ATO area touched not all police officers. The last group of them was evacuated from the ATO area in late July, when our troops looked set to begin a crucial stage of mopping-up terrorist held regions. Prior to that, about a third of police officers remained on the ground and performed purely formal duties. There has been a thorough purge of Ukraine’s, and especially the Donbas’s law-enforcement agencies. The military situation has exposed many shortcomings in staffing of the police. Most importantly, the traitors who served in the law-enforcement system have revealed themselves. Law-enforcement personnel were screened, so to speak, naturally, over the summer, at least in the eastern regions of Ukraine, where criminals have long lived in particularly high numbers. How will the purge of the police be held? This presentation just hinted on doing a test. Testing, including polygraph, is a very useful element for selecting candidates to work in the security forces, but lines and test questions are not enough to screen the police (now still militiamen). For tangible results to come from the reform, it should employ more radical approaches to appointments, otherwise this reform will eventually reverse and eliminates possible improvements.

Member of the MIA’s Expert Council Oleksandr Banchuk said back in May that the main objective of the reform was effecting a fundamental change in the status of the police – namely, transforming a paramilitary force into a service tasked with providing services of security and order. It should be understood that any reform still will not give answers to the question of making a particular employee conscientiously perform their activities following the rules prescribed in the law. The complete control of the ossified system by the public is now almost impossible. Thus, any representation of the concept now, unfortunately, is just a shell, appropriate for the election time. Disregarding for a moment all political aspects and focusing on the urgent demands of society regarding the reform of the MIA, it must be admitted that the Georgian experience is the only way forward. This means that the minister, who now leads an active political struggle, has to oppose his own subordinates. Of course, no one will do it, especially in such a crucial period in the political sense. No wonder that Kakha Bendukidze, a famous Georgian reformer, has left Kyiv and returned to Georgia disappointed.

“We did not listen to the advice of our European well-wishers who advised us to carry out our reforms gradually,” former minister of internal affairs of Georgia Vano Merabishvili once said. “We have taken a very rude action, firing 15,000 MIA employees in a day.” Who will take such a suicidal step in Ukraine, especially given the demand for former employees of security agencies in the conflict now raging in the east of Ukraine? Deep reforms require unusually strong political will from the Cabinet, which is hard to discern so far. The short presentation of future changes by the Ukrainian minister of internal affairs, despite being full of slogans, does not give an ordinary citizen hope for a deep transformation of this branch of the state apparatus, associated with coercion and maintaining order. Renaming militiaman to policeman is easy, but what to do with the copper culture?