Eight years ago a considerable proportion of the world’s population celebrated the 2,000th anniversary of Christ’s birth. During these last two millennia Christianity has changed in many respects, particularly the image of Jesus Christ. For a long time the early Christians, who were mostly subjects of the powerful pagan Roman Empire, considered that portraying Christ as a human was a mortal sin and a temptation for the faithful.

The situation began to change noticeably during the age of Constantine the Great (4th C.), who stopped harassing Christians. (A large part of his army consisted of Christ’s followers.) In the newly-founded capital of Constantinople, the emperor ordered a huge column to be erected and crowned with a statue that combined a pagan image of the Sun, the Messiah (Jesus Christ), and the emperor himself. This “assortment” was typical of those times.

Today much has changed in the Christian world. The faithful, especially Orthodox and Catholics, simply do not believe, and even take offense, when they learn that it was categorically forbidden to depict Christ (in icons, paintings, statues, engravings on little brass crosses, etc.). It was the Christian clergy, not the enemies of Christians, who imposed this ban. It was not until the Second Council of Nicaea (787) that icons (“images,” “portraits”) and worshipping them were solemnly permitted.

But during the persecutions of the early Christians, most of them considered that a concrete image of the Son of God was a major sin and similar to the creation of pagan idols (in which many residents of the Roman Empire believed at the time). Taking refuge in catacombs and building their first temples there, in their liturgies Christians used fire and some symbolic marks, such as monograms of Christ’s name, the sacrificial lamb, and others.

The problem of construction and ritual decoration emerged only once Christianity was “legalized” and its followers left the catacombs and other shelters, and began to hold religious services openly.

This problem was all the more pressing because Christians were very reluctant to “take up occupancy” in the former pagan temples dedicated to Jupiter, Venus, Mars, and other gods. The best places for worshipping Christ in the first centuries of legalized Christianity within the confines of the Roman Empire were the so-called basilicas, buildings that housed a Roman court or commercial center. They were rectangular in shape, with rows of columns and a semicircular niche with a crypt. Excavations and extant documents prove that Christians used basilicas for religious services all over the Roman Empire.

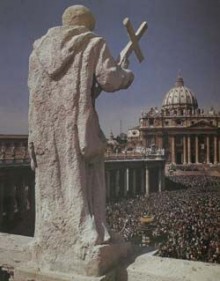

Later, they began to build special Christian basilicas, like St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, where centuries later the majestic St. Peter’s Church was erected. Among those who built and decorated this church was the famous artist Michelangelo.

At the dawn of Christianity, the interiors of basilicas were simply decorated with symbolic pictures from the Bible, in keeping with the belief that sculptural images represented idolatry and the creation of idols even when biblical subjects were used. It was forbidden to reproduce the image of Christ both in painting and sculpture. The main reason for this was that the Jewish apostles treated every sculpted image as an idol: the Jews did not recognize painting at all because the Old Testament forbade it. They looked down upon it, as though it were a pagan superstition.

Christian feelings were fueled by inner, rather than outer, images (as is the case today in many Protestant churches). Pious emotions were aroused by images of a dove, a lamb, or Christ’s initials. The rooster was also popular, because it was thought to “announce the coming dawn.” (Even today roosters crown the spires of ancient Western churches.) The lamb, a symbol of meekness and sufferings, a paschal sacrifice - the symbol of Christ’s sufferings - was highly esteemed. (Since the split with the Roman Catholic Church in the early 16th century, many Protestant churches have observed, in keeping with the customs of the early Christian communities, the practice of decorating their houses of worship only with traditional symbols).

The ancient Romans, who witnessed the founding of Christianity, could not absolutely accept worshipping a “man” who was unable to save himself and faced an ignominious death on the cross. They were convinced that Christians worshiped a crucified wrongdoer. It was also difficult for the Greeks to accept the new God: for a long time they tried to avoid illustrating their evangelical texts with scenes depicting the brutalization of Christ.

Crosses did not acquire a sacred meaning at once: for a long time believers confined themselves to the sign of the cross. In the Roman Empire T-shaped wooden crosses were the main instrument of torture and execution. (Today, gallows play the role of ancient crosses). It is thus clear why the first Christians (Judeo-Christians) did not have even the outlines of crosses in their secret temples. Once sacred metal crosses appeared, for a lengthy period of time they did not portray the figure of the Crucified Christ. A dove with an olive branch was the symbol of the Annunciation. When Christians dared portray Christ, as a rule He was depicted with no marks of suffering on His face.

The first full-fledged depictions of Christ began to appear only in the 6th century. Artists usually painted him nailed to the cross, dressed in a long tunic, with a serene and peaceful face. The head was crowned with a golden nimbus borrowed from the gods and heroes of other religions. For example, Julius Caesar was pictured with a halo of gold rays around his head. The heads of emperors were also encircled by nimbuses.

Bright and richly-decorated icons, sculptures, and painted canvases depicting sacred history appeared much later. When depictions of the naked crucified Christ with a loincloth appeared, many Christian communities were outraged and called these crucifixes obscene.

One of the earliest and most expressive images of Christ is a 6th-century painting from St. Catherine’s Monastery located at the foot of Mt. Sinai. This is an ideal face of the Divine Man, who is calmly and sorrowfully gazing at the world and its people; His face reveals absolute wisdom and sadness.

Another essential and natural feature of the images that were recreated on canvas, wood, or metal is that Christ, as well as the apostles and saints, always resembles the nation to which believers - especially artists - belong. Some medieval Christian authors believed that there were many flaws in Christ’s appearance and that this is the way it is supposed to be because the Son of God’s physical beauty would only have distracted His disciples from His sermons and prophesies. Some theologians were convinced that “a great spirit could not have lived in an unworthy body.” St. John Chrysostom, for example, was convinced that Christ was the most handsome man on earth.

Most contemporary scholars reject the hypothesis that images of Christ from when He lived, including all kinds of shrouds, have (or could have) survived. Interestingly, this coincides with the opinion of certain learned monks of the Middle Ages, including St. Irenaeus and St. Augustine. The latter pointed out that all the known images of Christ differed one from another.

(Sources: A History of Arts by Petr Gnedich and Grosse Illustrierte Kirchengeschichte )