The exhibit shows about 70 most valuable Iranian antiquities from the collections of four national museums. “According to the tradition preserved in Denkart, a Pahlavi book of the 9th century A.D., three nights before Zarathustra’s birth his mother was so radiant that the entire village was illuminated. Thinking that a great fire had broken out, many inhabitants hurriedly left the village. Coming back later on, they found that a boy full of brilliance had been born. Likewise, at the birth of Frin, Zarathustra’s mother, the house appeared to be on fire. Her parents saw her enveloped in a great light… The text explains that her great radiance was due to the xvarenah (xvar [abstract divine essence, a fire-related charisma that embodies the supreme heavenly principle]) was in her,” the famous historian of culture and religion Mircea Eliade wrote in the book Occultism, Witchcraft, and Cultural Fashions.

One can learn what the divine xvar (wisdom, divine choice, power, success, etc.) was in the imagination of ancient Persians by visiting today the Khanenko Museum in Kyiv. It holds a unique exhibit, “Charisma of Iran,” that displays about 70 12th-19th-century rarities from the “Iranian collections” of Ukraine’s four museums: the Khanenko Museum, the Odesa Museum of Western and Eastern Art, the National Museum of the History of Ukraine, and the National Kyivan Cave Historical-Cultural Preserve.

“It is Bohdan Khanenko himself who founded the collection of Iranian antiquities,” Hanna RUDYK, exhibit, curator, deputy director general of the Khanenko Museum, says. “Bohdan Khanenko had a flawless flair for art – he acquired the most valuable pieces of our collection which consists of almost 400 items now.”

Among the most valuable artifacts of the “Charisma of Iran” are, above all, very finely embossed brass items. Ordinary household objects thus turn into priceless valuables thanks to an intricate pattern of their ornamentation.

“For example, you can even discern the whiskers and teeth of lions on a 13th-century floor candlestick,” one of the exhibit’s most interesting artifacts,” Rudyk points out.

In ancient Iran, the lion was a symbol of royal power and grandeur and of the Sun itself. In general, an “initiated” spectator will easily make out the symbolism of the art “from bird to fish” (the Iranian saying “murgh-o-mahi” means the limit of the Universe). For the winged creatures, birds, have symbolized the sky and fish – the earth in Iran from times immemorial. It was believed that the king (shah, shahanshah) reigns supreme over the life of all creatures between the sky and the earth. Therefore, no matter what the case was, Iranian artists first of all meant him – the bearer of the xvarenah-“charisma.” The shah himself was depicted bazm-u-razm (“from banquet to battle”) as a courageous warrior or man who celebrates victory.

The exhibit is rich in the “charismatic” glitter of gold even without the metal itself. First of all, all the embroideries are adorned with gold threads. “This is the 18th-19th-century Iranian embroidery on velvet. It is drawn very well, with a sense of taste, the velvet is chosen skillfully, and ‘cross-stitching’ looks superb owing to golden and silver threads. But the main attraction is the inscription ‘Do not be too proud and never take the place you are not prepared for. This is the gist of glory!’” the exhibit curator comments. And the high-cost 17th-century phelonion (a liturgical vestment in the Eastern Christian tradition) is, in her words, convincing proof of Iran’s international ties. Moreover, it was re-stitched several times, with more gold added. This happened in 18th-century Ukraine. In the very beginning, the main part of the phelonion was made from fragments of invaluable Iranian silk. It is the famous Shah Abbas (1571-1629) who set up the production (to be more exact, put under his control and organized the export) of the latter. Valuable Iranian silks continued for a long time to serve as perhaps the country’s main “currency.” They were presented to the rulers of other states as a token of respect. They were also the embodiment of “charisma,” for only the wealthiest and most noble people could afford to wear them.

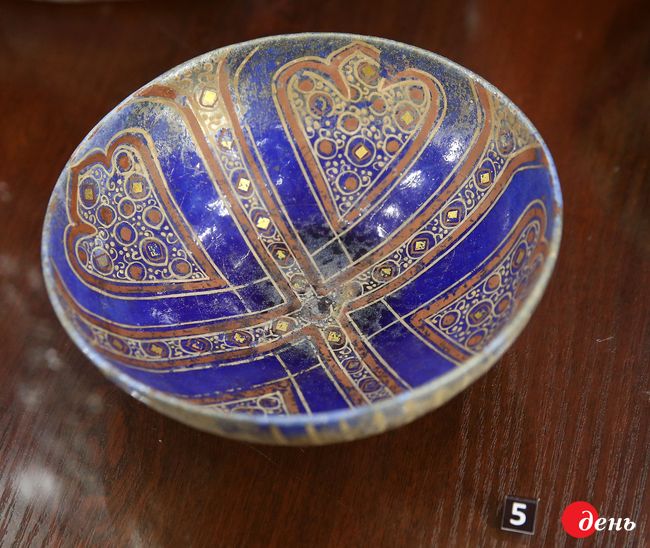

Of special interest at the exhibit is painted faience and marvelous miniatures. Where else will you have an opportunity to see precious cups and plates – the tableware of Iranian shahs? What also charms you is “Bahram Gur’s Hunt,” a 1227 valuable glazed tile showing a camel rider, a true gem in the Khanenko collection, so far the only dated object of Iran’s mirror ceramics with a Shahnameh theme. You can also feast your eyes on the legendary “Mirage,” a 16th-century manuscript miniature that shows the Prophet Muhammad riding up across the blue nightly sky on the miraculous mare Al-Buraq to heaven to meet God. The colors are bright and juicy, the forms are filigree, and the flight and aspiration are expressed very skillfully. Everything is shining and flickering, and angels are flapping their wings.

Each of the items has a detailed description that includes not only the date of creation, but also a historical reference about its symbols, value, and place in the history of art.

The exhibit will remain open until February 11, 2018.