Contemplating the canvases by the artist Valerii Franchuk, filled with bright, saturated colors, often helps spot the same colors in the surrounding world. Franchuk has gone a long way before establishing himself as a painter: a pupil to Mykola and Alla Mazur in Khmelnytsky in 1972-73; a student of the Kyiv Institute of Arts in 1980-86 (which he entered only on his third attempt); participation in 105 exhibits (collective and international), and 130 personal exhibits. Now he is a winner of the Taras Shevchenko National Prize and a Merited Artist of Ukraine.

Over 28 years the artist has executed more than 3,000 paintings and more than 700 graphic works, a considerable part of which are now on display at Ukraine’s best art museums. The master is reluctant to talk about his hardships, emphasizing that it is his optimism that helped him to overcome them. The urge to work and the persistent ability to outpace time makes the works of this buoyant painter really exceptional. Yet the buoyancy in his canvases is not shallow and entertaining; it is deep, sometimes even tragic.

Franchuk works with various subject matters and genres. His cycle “Ode to the Creator of the World” is permeated with admiration for picturesque nature; “Silence of the Old City” is dedicated to Kyiv; the series “Peace on You!” was inspired by religious themes. Subjects of Ukrainian history are also dear to him (and include cycles of paintings about the Holodomor, Chornobyl, a series of portraits of outstanding Ukrainians).

Recently Franchuk finished working on illustrations to a book of Pavlo Tychyna’s selected poems, Poslav Ya v Nebo Svoiu Molytvu (I Sent a Prayer Up in the Sky), published to commemorate the poet’s 120th birth anniversary.

It is clear that an artist’s talent has no nationality, and a genius does not know any borders. Yet do you think an artist must “interfere” with the process of nation-building? What role can artists have in the reconstruction of historical memory, overcoming the post-genocide syndrome, and bringing society back to a normal reference system? Is an artist capable of influencing such deep and complex social processes at all?

“This is a very important question, and the answer to it depends on the person. If the history of one’s homeland is dear to the artist, they will sooner or later address this theme. Some artists call themselves cosmopolitan but, as a rule, it is sheer deceit. Everyone has special feelings to that spot on earth where they opened a channel connecting them to the universe, the spot where they were born and belong. The notion of cosmopolitanism is very often used as a disguise for their Janissarism. A lot also depends on wheather the artist really will take up something truly important. Many would have Ukrainians forget their genealogy and the roots that keep their souls alive. People with dormant or dead souls are nothing but biomass or mutants.

“Just like any other community, a nation needs its elite, people with a vision of the right path for the development of their fellow countrymen. Ukraine has a wealth of such people, but on the level of state policy, they are all ‘drowning’ in the River of Oblivion, instead of having their names written down in the Book of Memory. By the way, very often an apolitical individual can change his or her world outlook and views on history and modernity exactly due to coming into contact with such people, or their work.

“An excursus into history, even the more recent, will show that all manner of artists (poets, writers, film directors, or painters) have always been under the close supervision of the KGB. The secret police were well aware of the influence art exerts on people. They must have had a good reason to send artists to camps — Sandarmokh, the GULAG, the Solovetsk Islands; others were just shot, like Ukrainian kobzars [performers of traditional songs to the accompaniment of the kobza, a plucked string instrument. — Ed.], or boychukists [followers of painter Mykhailo Boichuk. — Ed.].

“If I didn’t believe that an artist can influence social processes, I wouldn’t have created my polyptych The Road of Hetmans, hoping to awaken the consciousness and conscience of our leaders, or the cycle “The Tolling Bells of Memory” and the series “Chorna-Byl” (The Black Pain), appealing to the genetic memory and moral sense of our elite. Maybe, it will help strike a chord… I am convinced that no technologies will be able to destroy our nation’s memory.

“Looking at the present state of social and political life in the country, I cannot just stand aside, or desert into the so-called installations or ‘nonfigurative art.’ My conscience won’t allow me to.”

How do you pick the subjects for your paintings?

“You know, they suggest themselves… A lot of things I paint have never been seen in reality — they come from intuition, the subconscious, and take shape as ideas, images, and landscapes. For example, this is true of my first painting, The Mew. Mother would often see me off to the bus stop, a shawl over her shoulders, and a wave of that shawl was like a blessing for a safe trip and return. Once in the dim light of the dawn it seemed to me that in the distance she was turning into a mew. This is how the painting was born.”

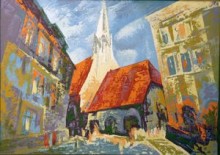

Churches are present in many of your works. They are always different, but at the same time they have something in common.

“It is one and the same image, but represented in different ways on the canvas. I still often see this image in my dreams. A wooden church in my home village Zelena near Khmelnytsky, built by my great-grandfather Stefan Kobyliansky and his fellow villagers.

“But in 1965, the ‘emissaries’ of the Soviet regime dismantled the church. They took off the bells at night, doing it all fast and in secrecy. It was a tragedy for the entire area. For example, the picture Dreaming of You showed this deserted, old, ruined church. The invisible image of my great-grandfather, the builder, is very dear to me, too. From time to time it comes up in my memory, as if blessing me for further work.”

“The Tolling Bells of Memory” is a cycle dedicated to the victims of the Holodomor of 1932-33. From a psychological perspective, is it hard to work on such canvases. How long did it take you?

“The cycle comprises 126 paintings, and took me 17 years. Mother would tell me a lot of grim stories. Our family was also affected by the disaster, just like millions of other Ukrainian families. What helped me continue the work was the awareness that people in Ukraine and the world must at last learn about this horrible truth, the hideous crime committed against the Ukrainian nation. And since it is hard to realize it, the artistic expression is also difficult beyond words.”

Your paintings often tell sad stories. Yet, strangely enough, they do not leave the viewer depressed.

“I believe in man’s kind soul, I believe in God and, despite all the hardships, I try to keep this faith.”