Early in the morning of January 12, 1972 a group of men with KGB IDs stormed into Lviv-based artist Stefania Shabatura’s small apartment to search her as a witness in Viacheslav Chornovil’s case. The artist, accused of spreading the underground self-published literature (samizdat) and in particular Vasyl Stus’s typewritten collection Vesely tsvyntar (“The Merry Graveyard”), was arrested.

According to the archives of the Security Service of Ukraine, analyzed by young historian Olha Ihnatenko, senior investigator of the KGB of Ukraine in Dnipropetrovsk oblast, lieutenant Oleksandr Pokhyl, was charged with the investigation of this criminal case. Besides manuscripts and typewritten materials discovered during the search, the investigator got interested in the artist’s two tapestries, Cassandra and Lesia Ukrainka, which had been photographed by the USA national Natalka Pylypiuk for the Institute of Modern Art in Chicago.

On February 24, on the investigator’s orders, these tapestries were confiscated (although restored to the author later) as works containing “elements of nationalism” and involved in the investigation. The KGB looked for hidden ideological contents of “nationalist nature” in the concept of the works, prowled for blue-and-yellow combinations of the tapestries’ bright, decorative color schemes. In this “Case No. 203” (anti-Soviet slander and calumny) a number of artists were interrogated, including Emmanuil Mysko, Karlo Zvirynsky, Oleh Minko, Andrii Bokotei.

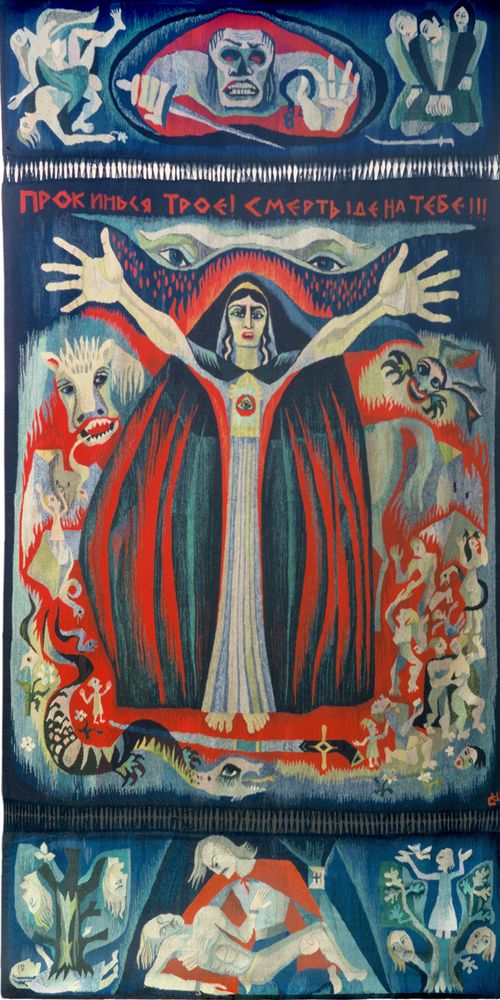

Cassandra / Photo replica courtesy of the author

Following the investigator’s question (what idea underlay the composition of Cassandra, the tapestry in which the theme of the fall of Troy was considered as a symbol of treason and perfidy), on April 1972 an art expert examination group was summoned. The expert examination was conducted by lecturers of the Lviv State Institute of Applied and Decorative Art: artists and associate professors Ye. Arofikin and D. Dovboshynsky, and art critic, senior lecturer V. Ovsiichuk.

Despite a rather objective and restrained review, the works by Shabatura (who then turned 33) were deemed “harmful” by the KGB investigators. Thus on July 13, 1972 the artist was convicted under Article 62 part 1 of the Criminal Code of the UkrSSR to five years of harsh regime camps and three years of exile. She served her term at the women’s concentration camp in Mordovian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, and was exiled to the village of Makushino, Kurgan oblast.

Shabatura was born on November 5, 1938, in the village of Ivane-Zolote near Zalishchyky (now Ternopil oblast). The girl, who had an extraordinary talent as a drawer, finished an art school and later, in 1967, the textile art department of the Lviv Institute of Applied and Decorative Art. Her first work Khodyt Dovbush molodenky (“Young Dovbush a-Walking”), executed in the plane ethnographic decorative manner, brought recognition to the young artist. She designed and wove tapestries which were exhibited at numerous art exhibitions: Na Ivana Kupala (“Midsummer”), Ivan Kotliarevsky, and David Guramishvili. Writers of Ukraine to Writers of Georgia. She was an active participant of Prolisok, the Lviv-based club of young artists where they revived the tradition of Ukrainian Nativity shows. In 1969, Shabatura was admitted to the Union of Artists of Ukraine.

Meanwhile, together with Iryna Kalynets, Shabatura initiated “the dissident movement” in Lviv. Together with poet Ihor Kalynets, author Mykhailo Osadchy, art historian Bohdan Horyn, painters Ivan Ostafiichuk, Volodymyr Fedko, Bohdan Romanets, and Ivan Kozlyk they actively explored Ukrainian art of the 1920s-1930s, spoke with Yaroslava Muzyka and Okhrim Kravchenko, the pupils of professor Mykhailo Boichuk, the creator of Ukrainian monumental art who had been repressed by the Soviet regime.

In her art, Shabatura sought to express herself and oppose the obsequious totalitarian system which replaced “Khrushchev’s thaw.” While the “painters of socialist realism” created heroically pompous images of steelworkers and milkmaids, she was trying to rely in her art on the monumental imagery of the artists of the 1920s-1930s, adding a national, yet plane-style features, so characteristic of European avant-garde of the early 20th century.

The tapestries Cassandra, Lesia Ukrainka, and Vatra (“Bonfire”) turned out to be iconic in her artistic and personal life and caused a crucial turn in her fate in 1972.

The three-part composition of the tapestry Cassandra. Troy, Wake Up! Death Is Coming Unto Thee! is strikingly expressive and laconically monumental. In the middle Cassandra the foreseer, against the backdrop of apocalyptic battle is interpreted as Oranta, Mother of God trying to shield her people from enemy’s invasion. Below Cossack Eneus is supporting his dying wounded friend. And above is a fierce monster, the enemy holding a saber and chains: bloodthirsty, eager to kill, capture, and enslave. Due to the specific decorative character of tapestry and the monumentality of the created image, the work was perceived somewhat different than the naturalistic socialist realism pieces and, of course, shocked the “art critics in plainclothes.”

On December 2, 1979 her exile expired, and Shabatura returned to Lviv. As a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group (which she joined back in exile) she was under constant administrative surveillance. Meanwhile, she resumed her artistic career: over the years of her captivity, the KGB expropriated and destroyed 70 bookplates and over 150 drawings. Watercolors, beaded necklaces, tapestries, and woven bedspreads covered the walls of her atelier.

In the late 1980s the artist was active in the Lviv organizations of Memorial, the People’s Movement of Ukraine, and struggled to revive the repressed Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. In 1990-95 she was member of the first democratic convocation of the Lviv City Council, which on its session of April 3, 1990 decreed to hoist the blue-and-yellow flag above the City Hall. The flag was hoisted in a solemn ceremony by legislators Zinovii Saliak, Yevhen Shmorhun, and Shabatura. In 1991 she led the revived St. Maria charitable society.

In the last years of her life, despite health problems, Shabatura visited weaving and tapestry plein-air workshops in Yavoriv near Kosiv, was in charge of the Maria society in Ruska Street, and sought sponsors who would finance the restoration of the Church of the Presentation of the Lord where she was a parishioner. Modest in her life and consequent in her actions, she never asked for anything for herself personally until her very death on December 17, 2014, following a grave illness.