What has society seen and remembered over the past days, weeks and months? Ruins, vandalism, brutality, provocations, invectives, and filth. The Red flag has returned to Ukraine and there have been a fight of thugs in the heart of Galicia. There have been social polemics — whether Russian pseudo-patriots vs. Ukrainian pseudo-patriots. Drunks looted Olha Bohomolets’s museum in Radomyshl, which was built brick by brick from the dump into which the famous paper-mill of the 17th century was turned by Soviet and post-Soviet authorities. Series about bandits and Cheka servicemen on TV have been supplemented by no less exciting shows authored by secret services: military characters chase the opposition, historians, writers, and university rectors.

Still, the country is making merry in spite of the oligarchs’ assaults. Obscure figures triumph in literature. Loud “against-everyone-voters” are protesting against the current state of affairs with alcoholic tours. “The last barricade” is the cocktail they drink, while “Muscovite’s blood” and “kosher salo” are on the menu. Russians, too, have a favorite game, “to kill a khokhol.” Everything is a game. In Cherkasy region a Khmelnytsky monument was dishonored, a trident was knocked off from the independence monument in Kharkiv, swastikas were painted on the walls of the Sumy mosque, Kharkiv’s mosque was burnt down, and the Holocaust monument was dishonored in Dnipropetrovsk. Xenophobic spam roams the virtual space just days after May 9. But nobody cares: in the videocratic world everything that happens in the morning is forgotten before noon, nobody ever recalls what happened The Day before yesterday. Nobody takes interest in what happens tomorrow.

Nobody remembered that this May marked the anniversary of one of the greatest artists not only of Ukraine, but of Europe as well, maybe even of the world: on May 12 Ivan Marchuk turned 75. Only his native land, Ternopil region, celebrated the event. The Ukrposhta (Ukrainian Postal Services) issued an artistic envelope with Marchuk’s picture Awakening; on May 12 commemorative cancellation ceremonies took place in Kyiv and Ternopil. That was his beautiful Ukraine, awakening from the stupor, coming back to life in the triumphal colors of gold and blue.

Meanwhile, the artist has recently said in an interview, “No normal talent has ever sprouted up in this country, because the state is its burial ground.” He also said: “Our leaders keep repeating: ‘We are building Ukraine.’ But in reality they are building a pseudo-state with a pop-conscience. In a nutshell, this is a grave for unique people, talented people, a burial ground for all things progressive and extraordinary.”

There is pop-conscience, but no real conscience whatsoever.

The artist came back from the US recently only to say: “For in my time believed I that I was coming back to an independent and free Ukraine. I should not have returned.” The artist’s 12-year stay in Australia was like a paradise: there were exhibits, interest, and conditions for work. And in America he worked tooth and nail: he painted over 90 pictures in one year. About Ukraine he says: “I have been in Ukraine for 10 years. These have been 10 years of nerve wrecking, 10 years of negatives. I am working here simply not to lose my mind.” What are his days made of? “I have this stupid radio, which produces news every hour. For some reason I listen to it every hour. If I am living here, this is my disease, my drug. I cannot get myself cut off from social life […]. Everything that is going on around me has a certain imprint upon me. How does my day begin? I buy several newspapers on my way to the studio. […] No, I don’t admire any peculiar opinion or political stream. I take several views and then build my own line. I perceive all defeats suffered by my state as my own failures. Unfortunately.”

I remember the 1980s, when an astonishing discovery was made: God, do we really have such an artist?! We were being deprived of him through the 1960s — via bans, creating conditions impossible for work, and oblivion. I remember that he was severely criticized even when the system was agonizing. Marchuk was criticized for his pessimism: his colors were regarded as being too dull, too pessimistic — with such a sunny Soviet reality in the background! At the time many of his works (tens of them!) got lost. How can an artist survive this? “For I was beyond the board, under pressure, and when the slightest opportunity arose, I tried to show my works, so that someone saw me and knew about me. So I gave them to actors and artists, who had an opportunity to go abroad, or at least organize an exhibit in Moscow or other places.”

He says about his pictures today: “They should all be scattered across the world, because nobody needs them here.”

These are all quotations from a single interview (with Maryna Kryvda for Holos Ukrainy). Yesterday he was persecuted, banned, hushed up, and forgotten. We don’t know Marchuk, like we don’t know his teachers, the outstanding Europe-oriented artists Roman Selsky, Danylo Dovbushynsky, Karlo Zvirynsky, who are now forgotten and crossed out. Marchuk was not accepted to the Union of Artists twice. He was accused of “nationalism” and “formalism” — like all the Sixtiers (the artist was persecuted for signing a letter in defense of the Russian dissidents Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky). So in reality it seemed that Marchuk did not exist: exhibit halls were full of artless paintings depicting revolutionary leaders, farmers, and proletarians. His first exhibits, from the cycle “The Voice of my Soul,” took place in 1979-80 in Moscow — at the time the atmosphere in Moscow was, paradoxically, freer than in Kyiv. The artist’s first private exhibit only took place in 1990. He was over 50 then. Despite everything, he says: “The period of stagnation had no effect on me. I have understood long ago that a personal day of work is the greatest value life gives to a man.”

Today, when the International Academy of Modern Art in Rome has admitted the artist to the Golden Guild (it includes some 50 artists from the whole world!) and elected him an honorary member of the Scientific Council of the Academy, and he is on the list of “100 geniuses now living in the world,” there is still no place for him in his homeland. Pictures lie in his studio without any order for lack of room. If our state were civilized it would have organized at least 10 exhibits throughout the world. Marchuk has 4,000 pictures and a range of grandiose cycles, like “The Voice of My Soul,” “Landscapes,” “Flowering,” “Color preludes,” “Portraits,” “Expressions,” “Shevchenkiana” (“we are living under a single paternal roof, called Shevchenko,” the artist says), “Abstract Compositions,” “The White Planet,” “Dreams burst their banks,” “A Look into the Infiniteness”… A civilized state would have published albums, which could be an artistic calling card for our country.

However, we don’t even have a permanent studio-museum of Marchuk’s works in Ukraine. In 2004 the base of the museum was laid in Andriivsky uzviz. But the construction has not been finished. As a child he had no possibility to have an album — he got his first album as an adolescent. Today he does not have what he needs either. The previous president gave promises, but no actions (“Is it true that you know a president?” Marchuk was asked several years ago. He replied, “No, it’s the president who knows me.”) Besides, Andriivsky uzviz is no longer the Ukrainian Montmartre, rather a pandemonium of raiders who take studios from the artists. Pirates make copies of Marchuk’s pictures and sell them on the uzviz and other places.

And after so many years, after a pilgrimage full of suffering, there remains only one thing the artist can say: “I don’t care about [being called a] genius, titles or ranks. We don’t want to show the world the genuine things we have. My greatest concern is that people should have access to everything. But what can I do about this? This is a problem with the authorities, or to be more accurate pseudo-authorities, which do not want to improve, to show themselves and their homeland in a better light. We don’t want to show to the world the genuine things we have. For many years I have been offering many ministers of culture: ‘You want to create a positive image of Ukraine, I’m giving you my works — bring them to Europe.’ But all in vain. I cannot bring them on my own; I need a whole lot of permissions etc. This is a dead zone. Therefore I repeat, this is a grave for unique people. A burial ground for talented people. A burial ground for all things progressive. The only thing that remains is to sell the land and be done with it.”

What goes next? Does this state have any prospects? Marchuk does not harbor any illusions: “First, we should stop stealing, then we should put to end all hostilities. We need the Chinese, Malays, Africans, and best — Germans to come to our country. Germans won’t let us live badly; they won’t allow us to steal. They will simply earn money here with their work. But Ukrainians will never be able to govern a state, because God gave them a paradise, and took away their minds.” Who in this pop-culture state, governed by cheats and parasites, needs a man who perceives this world in such a simple and severe manner, almost like a Protestant? “We don’t speak about the holidays, because I don’t have any. My days are all alike. If I paint anything on Christmas, this is a holy cause. Whereas others drink and party, I work. I am not able to rest.”

Though they may harbor illusions, politics has no sway over artists. Marchuk is a “planet that rotates around its own axis and will never leave its own orbit.” His natural space is the sky: “If I was told to paint the sky and they gave me several thousand years for this, I would do it – without ever repeating myself.” (Taken from interview with L. Ostrovska and H. Salovska for Vilne Zhyttia plius – Author.)

“You paint lots of bare trees,” a journalist says in the quoted interview. “It’s because my nerves are bare,” the artist replied.

These nerves are like the strings of the universe in his pictures.

He says that he is going to visit the Chornobyl zone: “I want to make a whole cycle about this wretched land.” He has already painted its tragic images: The Chornobyl Chords, A Warning, A Ballad about the Clean Waters, A Postscript to the Red Book, The Chornobyl Madonna.

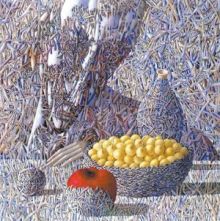

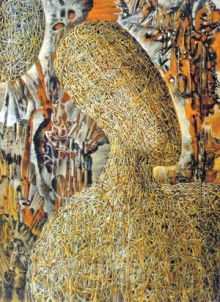

Marchuk is a magnetic interflow of light and darkness, a conscious and intuitive violation of perspective and proportions, a symphony of intertwined lines that has frozen as an unraveled ball, surrealism and realism in such a natural synthesis that they even create a unique extraterrestrial world. His concrete images are full of mystical accents and abstract vision, yet have distinctly outlined convulsions of reality. A distinct contour, and at the same time an interlacement of lines that are impossible to unbind. Broken Strings, Musicians, Color Preludes, A Requiem, Silent Strings, Melody, Symphony, Suite, Nocturnes are common names for his pictures. This befits modern painting, there is a synthesis of painting and music. And the big red apple on the snow among the small houses; epic pear trees, calmly resting on a river bank; the tall old people, frozen to the houses smaller then them — like shadows; saints and thinkers, through whom the eschatological emptiness of the world emerges. All this creates a stereoscopic symbolic of all things living and being.

Trees, people, beasts, birds, and dreams are a transcendent cycle of concrete meanings. Marchuk loves the winter, the fog and frost. It seems that if you touch a picture, you will immediately feel this cold. Nobody will ever know how he paints his pictures. Like his father, a weaver, who wove threads in a Ternopil village, the artist “weaves” thousands of threads. It is not about the technique. He painted these pictures from his dreams. The Apocalypses and nocturnes, the plastics of the praying silence, asceticism and a burst of life are followed by lots of flowers — of the most incredible shapes and colors. The flowers are cosmic and grow on a different planet. The frozen colors have become a monochrome gamma in the surreal landscapers of “White Planet-1” and “White Planet-2.” “I create all this for this paradise of a planet, yet I’m living in hell.” And Shevchenko’s Kobzar pictured by Marchuk features people without skin, woven of bare nerves and dry branches, shadows on “our, yet foreign land.” On the whole, old people in his pictures represent an eschatological image of the Holodomor, long time before the historians turned to this topic.

And suddenly conditionality appears, not people — personalities interlaced with color. Cubically broken faces of musicians with broken instruments, where Paganini’s fingers are squeezed in. And again, abstractionism, “The Fourth Dimension” — chaos gives way to meaning, a split matter develops into broken lines and cascades of colors. Unlike Jackson Pollock with his expressionistic abstractions, where sterile matter fades away, Marchuk’s matter is protesting, liberating itself from itself, creating and recreating.

Marchuk started with the “Voice of My Soul,” and now he is painting “A Look into Infinity.” One infinity is a continuation of another. He spent his childhood in a village in Ternopil region, where it is impossible to get paints, so he used flower sap — he made a watercolor of the Ukrainian flag, using blue and yellow flowers. He created mosaics — the iconostasis Yaroslav the Wise and Toward Faraway Planets — at the Institute of Theoretical Physics of the National Academy of the USSR in Feofania. He has lived in many corners of the world, including in the heart of Manhattan. And then he came to Ukraine, after all. He went on foot from Trypillia to Kaniv. He sought shelter. He had found one, because, they say, a peculiarly twisted apple tree was growing in the yard. It was calling out to him. He found it because there was water nearby, in order to paint the space from the threshold, to hold the morning sun in his hands, to enter the holy Dnipro River, like Hindus enter the Ganges.

Marchuk is a wizard, he can disappear all of a sudden and go painting. The artist’s house is an easel. “God has bound me to an easel.”

The artist came back not from America, but from space, and not to Ukraine, but to the cosmos of his soul, a soul of “free wanderer, bound to the easel.”

The world is “my palette and my studio. I will go ahead as long is I live — I will never stop. This is my essence.”

Marchuk says that freedom is the state of his soul, because he has painted lots of pictures, and a single one — the universe, illuminated by the brush in his hands.

COMMENTARY

Serhii YAKUTOVYCH, an artist:

“Ivan Marchuk is an outstanding personality in Ukrainian culture. He is an artist with a complicated life. Yet he is lucky. He has a talent, a God-given talent. At the time, according to Lina Kostenko, ‘the artist did not need any awards, as he was endowed by life. A man becomes a person when he has people.’

“Marchuk’s creative oeuvre is boundless, judging both by the number of works and themes. His pictures are philosophically composed. I understand him, his earlier and later works, and present-day works. When he was not allowed to exhibit his works, I came to see them at closed exhibits. Back in that time I was attracted by the philosophical contemplations on his canvases and their metaphorical nature. They say Ukraine has many talents. But nobody mentions how unfavorable the conditions are for their realization. I am glad that the master manages to work, in spite of everything. He did not wait for destiny to favor him; he painted and sought chances to show himself to the world. And he has found them, like in the saying: seek and ye shall find. A genius artist needs to hear from time to time that he is a genius.

“I congratulate Ivan Marchuk on his 75th anniversary. I am happy to live in the same period of time as he.”