Yevhen Sahaidachny may justly be called the least studied of the greatest Ukrainian artists of the 20th century. The exhibition’s curator, Doctor of Arts Oleksandr FEDORUK tells us that his works were outside the museum lists until recently.

“Sahaidachny belonged to the Boichukist circle,” Fedoruk says. “His works give an idea of the whole school. Moreover, Sahaidachny’s works expand the limits of the Boichukist phenomenon.”

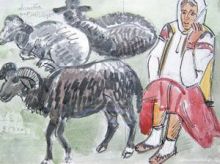

Interestingly, the artist was not a Hutsul by birth. He was born in Kherson. However, the student of Sahaidachny’s artistic heritage Maria Ivanchuk of Kosiv (Ivano-Frankivsk region) notes that Sahaidachny, despite being an Easterner, managed to integrate himself into the Hutsul applied arts, cultural, and everyday life spaces through his erudition, intelligence, and a great desire to understand the Hutsuls. As a result, the Hutsul country gladly shared with the artist the richest seams of its cultural and ethnic tradition.

Sahaidachny devoted 15 years of his life to collecting works of Hutsul folk art. The Sahaidachny pair gathered a unique collection of works of folk crafts and antiques after spending a few years in the Hutsul country. Dozens of artists, art historians, and students from all over the Soviet Union, including Moscow, Kyiv, Yerevan, Riga, and Tallinn visited them in summer. Visitors were not just interested in the exhibits, they were looking at them to find something for themselves, for their own creative growth. Sahaidachny copied painted Easter eggs, wood carvings, and brass decorations; he admired the forms of pottery, and found time for studying embroidery, weaving, carpet weaving, and traditional Hutsul clothing, too.

His works were mostly easel-painted. Fedoruk explains that Sahaidachny could not afford to paint in oil, as he was short of anything but tiny room, pencils, watercolors, and a desire to create.

“The artist is also considered to be the father of Russian avant-garde (Russian, not Soviet, because he never was a Soviet artist in his worldview). This role saved him in the 1930s from the charges of bourgeois nationalism and from execution by firing squad that followed such charges. After stays in St. Petersburg [where he painted scenery for theaters. – Ed.] and Kyiv, Sahaidachny worked in eastern Ukraine from 1932-46, and moved to the west of the country in 1947. The father of Russian avant-garde became the greatest custodian of Hutsul art after coming to Kosiv district,” Ivanchuk says.

The exhibition of his works in Kyiv became possible only after Sahaidachny’s artistic heritage was finally put in order in recent years, and, as Fedoruk tells us, this effort was greatly aided by the director of Kosiv Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts Sviatoslav Martyniuk and director of the National Art Museum of Ukraine Anatolii Melnyk. This is no small event, because such figures as Sahaidachny form the idea of the Ukrainian culture of the interwar period and the first half of the 20th century.

Sahaidachny’s works will be exhibited at the National Art Museum of Ukraine until January 29. Visitors are able to see some 80 works from the collections of the National Art Museum of Ukraine, the Andrei Sheptytsky National Museum in Lviv and the Yosafat Kobrynsky Kolomyia National Museum of Hutsul and Pokuttian Folk Art.