This time Huchnomovets, our music column, tells the story of one of Ukraine’s most interesting independent rock bands, Nameless (Ternopil) and looks at St. Petersburg’s celebrated NOM and the little-known but gifted Ukrainian industrial rock band Surma.

Surma’s weak martial industrial potential

There is a well-known Ukrainian presidential campaign slogan that reads, “This country will be saved by a new kind of industrialization.” This context is suitable for the CD album Allocutio recorded by the Kyiv-based rock band Surma and produced by the Tel Aviv-based recording company The Eastern Front in 300 copies.

Surma is into the martial industrial trend, something seldom heard on the Ukrainian rock stage. This rock band is a pleasant exception from the rule — a critic can focus on precisely 40 minutes of music without worrying about the band’s creative biography, simply because there is no such data available.

The first impression is that this band is a palimpsest of sorts, with a great deal of time spent studying the classical works in this style. Within a single rendition one can hear Laibach’s early romantic simulated fascism, Der Blutharsch’s cheerful front-line fracas, or Death in June’s neofolk white noise. As for the borrowed music, this band can be compared to Yegor Letov’s project Communism or the album Satanism. This CD has all the traditional martial industrial ingredients: the alarming ambient drumbeat with audio “scratches” and militaristic marches with texts added here and there. Central among the compositions on this CD is Men Among the Ruins. The philosophic backdrop is the end of world history, post-human society, and negativism, a common mixture for many other bands adhering to this trend. The Ukrainian context added to the effect: scenes from a national patriotic TV serial accompanied the band’s music, which was nothing to write home about.

Indeed, Surma’s industrial music potential is weak, although this could be interpreted as graphic reflection of the current status of Ukraine’s metallurgy. Surma’s martial industrial renditions echo the stillness of the machines at the Ukrainian steelworks and abandoned mines. They can be summed up as a hymn to the so-called economic crisis. Of course, the martial industrial style stopped developing when the legendary British band Throbbing Gristle fell apart. I suspect that it happened before Surma came to be, but making a timely escape from a time warp takes talent, too.

This album had a good press from among foreign dedicated networks, but I think that this was largely a tribute to the product’s exotic origin, not its acoustic characteristics. Anyway, 500 to 600 buffs of this trend aren’t likely to find anything new there.

Nameless revolution

In 1967, when London hosted the Congress of the Dialectics of Liberation that came up with a motto calling for immediate revolution and “genuine revolutionary consciousness,” the Soviet Union celebrated the 50th anniversary of the “October Revolution” and switched a five-day workweek. At the time, the revolutionary task of altering public consciousness that affected all of the arts in the West and North America failed to penetrate the Iron Curtain and worthily oppose the ideologues of communism.

The leader of Nameless, Zorian Bezkorovainy, says: “I think that our citizens should live through what Western Europe and [North] America did in the 1960s — a very interesting, heartfelt period in world history we were barred access to in the 1960s. Along with the civil liberties, there appeared the freedom of the arts.”

His rock band was founded in 1992 and it has since remained a veteran and most celebrated one in Ternopil. Nameless’ repertoire is rooted in the aesthetics of the 1960s, and their original renditions are performed in a nonstandard style. The name of the band is borrowed from Ursula Kroeber Le Guin’s book A Wizard of Earthsea and appears to best describe its main stand: maximum creative self-sufficiency and independence of all showbiz trends. In other words, this rock band doesn’t fit in the standard showbiz pattern, and the fact remains that in the years of its existence Nameless has defied all such standards. It doesn’t have a name to the liking of those at the helm of mass culture.

Nameless was among the first bands in Ukraine to start experimenting with performances and concerts with video accompaniment.

Says Bezkorovainy: “We believe that everyone in our concert audience should use all their receptors to the fully active. In the first half of the 1990s we performed in movie theaters and used film projectors. Later, in the 2000s, during the Reivakh Festival, we were among its organizers. There were special installations there that targeted the visual channel. We also enlisted volunteers who walked around the audience wearing boas and used them to tickle people in their seats. We made the best use of human receptors: hearing, eyesight, and touch. Those in the audience who were willing could also activate their gustatory receptors by drinking beer. The Reivakh Festival was a multicultural event that offered enough room for literature, drama, music, fine arts, and performances.”

The cultural revolution of the 1960s in the West, with its principle of translating art into life, found reflection in the synthesized forms of creativity, happenings, cinematographic experiments, and kinetic art.

It was then that the New Theater phenomenon emerged: it interpreted a play as the result of a team performance, aimed at ruining the conventional structure of perception. Back in the 1960s, the emphasis was clearly on the “material” of any given literary work rather than on its contents, because global integration between various arts began at the time. Nameless in Ternopil has been trying to follow suit throughout the years — not only because the musicians are interested in the Western culture of the 1960s. Bezkorovainy believes that favorable conditions started materializing in the devastated city right after the Second World War. Ternopil had lost almost all of its population and set about creating its microculture anew: “It’s a melting pot with the most variegated cultures, just like the United States, except that in our case it’s a Ukrainian city.”

Since Nameless debuted 17 years ago, a number of original rock bands have sprung up in Ternopil, including S.K.A.I., Ti, shcho padaiut vhoru, and OrAndzh. Bezkorovainy welcomes this creative upsurge in his city, all the more so that he and his rock band have done a lot to help it. He further believes that such bands are not epigones and that what they do comes from their hearts, just like it was back in the 1960s, even if those aesthetics was barred entry to the Soviet Union.

I asked him: “Do you believe that what happens in Ternopil is united by the aesthetics of the 1960s? Even though different rock bands are playing different kinds of music and no all of them accept this aesthetics, is it true that they are performing in the spirit of the 1960s?”

Bezkorovainy replied, smiling: “Here musicians don’t get in each other’s way. There is a very hippie-like atmosphere in this town.”

Another aspect that brings the Nameless musicians close to the conformist spirit of the 1960s are the specific ways they use to realize their talents and inspiration, along with their adamant refusal to change them to suit the market.

Back in the 1960s, the Western culture of protest turned into the most consistent and outspoken opponent of the consumer society philosophy. It treated norms as nondescript entities reduced to the status of the average and lacking expression. Norms could manifest themselves only when someone departed from what was considered normal in the direction of the individual. This brought the awareness of every individual’s value and triggered an eclectic renaissance. A “new reality” emerged in the 1960s, and the arts made inspired use of its images.

In 1997, Nameless found themselves among the winners of the Chervona Ruta Festival. This allowed the rock band to take part in more prestigious and better paying concerts, make concert tours, and participate in prestigious cultural events. However, the band had to make up its mind on whether to accept or reject the rules of the showbiz game.

Says Bezkorovainy: “When some of the [showbiz] big wheels started paying attention to us, they quickly realized that we somehow didn’t fit the established pattern. What is showbiz all about? It’s based on certain groups of people with a superstructure made up of parasites who are trying to make money and create publicity by using other people’s creative efforts.

“Here is a simple example. A performing group has created a song and wants to perform it during a concert. You can’t do so under the laws of this superstructure; you can only do so if and when this superstructure issues a press release, so the musicians who even have a CD album must make do with the old concert repertoire. That is why we often organize our own concerts.”

I asked: “Isn’t this situation a burden? A lot of musicians, being creative individuals, believe they can’t cope with it. You, however, seem to be able to shoulder the burden. Is it because you know precisely what must be done under the circumstances?”

Bezkorovainy replied: “Making arrangements for concerts is part of our work, so this doesn’t burden us. It would be hard for me if were told that that we have to perform in such and such way and orient ourselves on Deep Purple or Iron Maiden. Concert arrangements are part of our creative realities.”

This is how the Ternopil-based Nameless rock band has been performing for years, charged with the spirit of the 1960s. It is also one of the first local Ukrainian-speaking bands. It has taken part in concerts and festivals, including Rock Existence, Nivroku, Reivakh, Ternopil Presence, and Unizh Fest. It has recorded CD albums, including Grippe (1996), Shchos stalos u lisi (Something Happened in the Woods, 2007), Zhyvyi v Ternopilskii Filarmonii (Alive at the Ternopil Philharmonic Society, 2008).

Concerts by the Nameless band feature music based on the blues with psychedelic and shoe-gazing elements, a style that requires a great deal of guitar and synthesizer effects. Among their favorite Western counterparts are the Velvet Underground, Pink Floyd, and the Fiery Furnaces. They use video effects and every concert is advertised by attractive handmade posters at the entrance, made by the band’s singer Svitlana Frolova. These musicians believe that if the audience likes their music, it means that some of the people share their views.

Nameless has an Internet blog and community at vkontakte.ru, where you can read news about this band and download their music.

Counterculture is generally known to have emerged as a way to discard obsolete cultural forms; it appears when the official culture fails to conform to modern realities. Nameless has never applied this notion, yet its creative endeavors are focused on reviving the spirit of the 1960s in a western Ukrainian town.

Keen perception, eyesight, and hearing

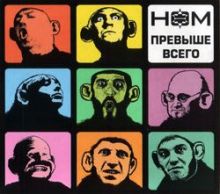

NOM launched its new album on October 9 in Moscow, several weeks before the bands arrived in Kyiv. This album stands out among others due to the fact that the musicians succeeded in putting together a dream team, the best one in the years of the band’s existence, including the initiators of the Informal Youth Association, Sergei Kagadeev, and the Geneva Opera’s “golden voice” Aleksandr Liver.

Their disk Prevyshe vsego (Above All Else) wins the audience the usual way adopted by the “Founders of the New World” — by bringing society’s verbal signals to an absurd level and by innocuously playing the game of replacing concepts. For example, the CD’s first composition “Mirotvortsy” (Peacemakers) is actually a summary of the Kremlin’s propaganda, so I guess it would sound natural when performed by pro-Putin youth movement Walking Together. The song contains pan-Slavic chauvinism and a negation of Western values.

NOM’s new album is a sequel to the Russian band’s favorite themes, including a parody of anti-Semitism, the torturous daily routine of the little man haunted by superstitions, and so on. As usual, NOM’s lyrics aspire for the aphoristic pithiness.

NOM is the acronym for Ne ochen molodyie (Not So Young), and each of its albums marked a noticeable cultural event in the 1990s. In the 2000s, each album has been received as a revelation. There is every indication that the latest will enjoy the same kind of welcome. Mazel tov!

Remarks, corrections, and comments can be sent to guchnomovets@gmail.com.