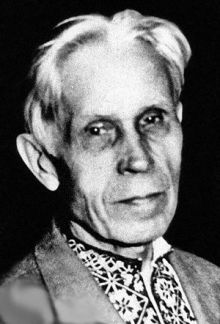

On December 16 the National Center of Folk Culture “Ivan Honchar Museum” has launched the project “Christmas is Tomorrow!” which is going to last until Epiphany. The event is dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the birth of the museum’s founder. Ivan Honchar (January 27, 1911 – June 18, 1993) was a talented artist and sculptor, ethnographer and dedicated collector. His oeuvre is equal to the achievements of an entire scholarly institution. He authored monuments to Ustym Karmeliuk, Ivan Gonta, Hryhorii Skovoroda, Taras Shevchenko, Lesia Ukrainka, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, Volodymyr Sosiura; portraits of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, Maria Zankovetska, Les Kurbas, Anatolii Solovianenko. Since the late 1950s the artist collected items of folk culture and household utensils (much to the displeasure of the Soviet authorities). In 30 years he gathered 7,000 items. He did all this with only one purpose: to let Ukrainians learn about themselves.

His centennial will be celebrated in different ways: almost a month of master classes on cutting, glass painting, baking spice cakes and carol singing; the animated video to the song “Shechedryk” by Oleh Skrypka, made by Sashko Lirnyk and Stepan Koval; the exhibit “Ukrainian Christmas: Symbols and Signs”; the event “A Night in the Museum”; the action “Twelve Christmas dishes in the circle of Ukraine’s famous families” (on the menu: Haidamaky pike by the music band Haidamaky, kutia by Nina Matvienko, uzvar by the Kapranov brothers), and a fashion show by designer Lesia Telizhenko. Further on the country will be toured by a traveling exhibit “Ivan Honchar: One Life’s Victory.” Also a book about Honchar is going to be printed in 2011, My Home has its Own Holy Truth — it has been written for nearly 14 years. Its author is the head of the archives department Lidia Dubykovska-Kalnenko, and the co-author is the collector’s son and current head of the center Petro Honchar. While the work on the manuscript is still underway, we offer for The Day’s readers extracts from another book, a book of memoirs.

Lidia DUBYKOVSKA-KALNENKO: “The book’s title is a quote from Ivan Honchar’s diary. ‘I will come from the city to my house-museum, and it will seem to me that I will have come from a foreign land to my native one,’ he wrote in April 1969 (recited from memory), ‘Khreshchatyk is swirling, Kyiv’s streets and institutions speak the language of our neighbors, yet a strange one, whereas my house is ringing with my native language, my native song. All over the city one creates lies about my people, and my house has its own holy truth and spirit of the people that warms up our weary souls.’ Honchar was born in a village. He created in his house, on a stove: he painted, modeled and cut there. It was his harbor. Even later, when he had an apartment in Kyiv’s center, in Artem Street, he nevertheless decided to build a house.”

Petro HONCHAR: “Maybe, for other peoples, the image of the house does not mean as much as for Ukrainians. Apparently, the reason is that for a long time we did not have a state of our own. Let’s recall Shevchenko’s words: ‘In our own house we have the truth, the power and freedom.’

“Once, soon after Ukraine became independent, I found myself in a military unit. It was in an empty former Lenin’s room, there was a single picture depicting a nice house. They said it was their amulet. So, on some subconscious level a house is more than a dwelling for us. It has a sacral philosophical meaning and is a symbol of Ukraine.”

L. D.-K.: “Many sought refuge in Honchar’s house — spiritual, psychological and emotional. This can be compared to the way a person comes to church: they will stand there, say a prayer, light a candle, and become filled with strength and come back to the world. It happened that a student came there for dinner, and those who had no place to go could spend a night there. There was a funny incident. A boy asked him to write a recommendation to enter a university. As a result he had to enter eight times, as Honchar was in the opposition to the Soviet power.”

P.H.: “People trusted him. Those were Soviet times: you had to have a license, saying that you represent a state structure, for which you are seeking antiquities. And the man was collecting items for his private museum. Wherever he went, people would give those items as presents. He frequently bought them. Speaking about the album Ukraine and Ukrainians, there are many photos of people’s families.

“The icon St. Nikita was found in the village Tarasivka, Cherkasy oblast — Shevchenko’s homeland. (Shows the picture) According to the Kobzar’s biography, he was taught by a deacon, who was very good at painting St. Nikita. It is very likely that the icon was painted by the same deacon, the young Taras’ teacher. To all appearances, the work was created by a masterful icon painter. And this one was most likely painted by Shevchenko himself (Takes another picture). Once Honchar came to Lyzohyb’s manor located in Sednevo, Chernihiv oblast. The gardener told him that there was an old church nearby, where Shevchenko used to paint, and there were all kinds of rubbish in the church-gallery. The picture was found in this rubbish. ‘This is Shevchenko’s manner,’ the collector kept saying, ‘It is Briullov’s school for sure. All women painted by Shevchenko resemble those created by Briullov.’ But of course we have no 100-percent proof of that.

“Honchar was very ambitious. He always wanted to be ahead of everyone. He liked when others praised him, which is typical of an artist. Suddenly he was told to stop his ‘nationalist’ activity, give all he had collected to the state, and admit that he was wrong in a newspaper. In this case he was promised to get great state orders and recognition. Here his ambition and idea ran into collision. His studio was set ablaze several times, he received calls with threats. He asked me all the time, ‘What to do?’ I am sure, he was going through a complicated inner struggle. But he stood up, owing to his friends, such as Lidia Orel, Leopold Yashchenko, Natalka Poklad, Mykola Kaharlytzky, Oles Fesiun... Incidentally, they all were on the KGB list, so to say, like those who visited our house-museum later.”

L.D.-K.: “The ethnographer’s diary says that 1973 started very sadly. Petrus and Nina came [Petro Honchar and Nina Matvienko. – Ed.] on Christmas Day. Nina said that her brother, who served in the army in Germany at the time, was asked, whether he went to the sculptor Honchar’s house on his trips to Kyiv.”

P.H.: “He set a task before us, to bring to the museum 10 people a week. This was a great enlightenment work. The spiritual army was shaped. He never perceived his numerous collection as a museum collection. Nothing was kept in a depository, but rather embellished the house. He did not want to simply give an asylum for the precious cultural items, which were disappearing or could vanish, unless he found them. He wanted to create an environment, where a person could feel their identity.”

L.D.-K.: “People came, saw the embroidered shirts and recalled that the same shirts were lying hidden in their grandmothers’ trunks. Moreover, the same icons would stand in their houses’ corners. This was how people started to understand who we are.”

P.H.: “Here, at the museum entrance, an entire Ukrainian family is collected in photos. Everyone can see himself or herself there – in the mirror [The mirror is placed among the works in such a way that when somebody looks in it, he will be added to the family tree. – Ed.]. The expositions of our museum, perhaps for the first time in the entire history of Ukrainian museum studies, ‘showed’ people: the collector gathered over 20,000 photos of Ukrainians of late 19th — early 20th centuries.”

Ivan Honchar built this museum for us and stated: “This is your home. Don’t let foreigners tell you how to live here, because you yourself have created it. With your hands. With your hearts. It is ascertained in our traditional art and folk culture. So, live at home if you want to be happy.”