It often happens that in art history extraordinary people are only remembered as authors of only one work (a book, a painting, a song, or a building), albeit each of these outstanding men or women has a wealth of hidden, obscure, or simply forgotten aspects to their personalities. We remember Edvard Munch’s eerie masterpiece, The Scream, but we can hardly name other pictures by this Norwegian artist. Likewise, we remember Taras Shevchenko as a poet, but his no less brilliant paintings are seldom mentioned.

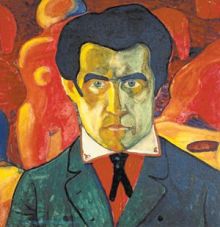

Similar is the fate of Kazimir Malevich, one of the most controversial artists of the previous century, whose name is mostly associated with the Black Square (the other name being Black Square against White Background), which automatically supplants other dimensions of his art. Most people have no idea that Malevich’s avant-garde, known as suprematism, is rooted in traditional Ukrainian culture.

The future pioneer of abstract art was born in Kyiv into a Polish family. The first child, he had four younger brothers and four sisters. He was born in 1878, a year of important historic events (including the change of the political map after the Berlin Congress), as well as developments in cultural and social life. However, these sweeping changes never affected young Malevich, who did not live in Kyiv, then a relatively small European city. Since his father’s work required frequent trips, it was easier to raise the children in the country. Their upbringing was virtually left to their mother’s responsibility. She instilled in Malevich the love for not only nature, but also for the Ukrainian people.

Besides, quite unexpectedly, he picked up a totally “unmanly” hobby, embroidering and knitting, which for some reason he found more exciting than working in the sugar-beet fields. It was the austere black and red lines of the embroidered patterns that laid the foundation of Malevich’s non-objective painting. Later the artist would say, “I have destroyed the ring of the horizon and got out of the circle of objects.”

In the country his family was surrounded by songs, fables, and legends, as well as by hard chores, which were also imposed on his younger siblings and which thus made a lifelong impression on him. His life took its quiet and slow pace, leaving in Malevich’s memory the eternal images of nature, picturesque landscapes, and people who loved and cared for their land with all their heart.

Each year his father, Severyn Malevich, took Kazimir to a sugar refinery fair, since he worked as an engineer at a sugar refinery. The fairs naturally took place in the more industrialized and civilized Kyiv. The city amazed the boy with its bustle. It was also a center of the art movement, which Malevich was soon to come into contact with.

One episode played a key role in the boy’s fate. Hanging out on the city’s crooked streets, he saw a picture in a shop window, portraying a girl peeling potatoes. This trivial, simple, and almost ritual rural scene aroused unusual emotions and shattered the boy’s soul. It was not the object depicted that mattered; it was the very phenomenon of painting. Malevich had never suspected that the world could be stopped still. He burned with a desire to learn who and how had done it. The urge to see behind the paints and canvas became the goal of his whole life.

Once in a little town of Bilopillia near Kharkiv Malevich met church painters. Several renowned artists had come from St. Petersburg to paint cathedrals, which in Ukraine was quite a common practice (the one instance being Vrubel’s paintings in St. Cyril’s Church). For the first time in his life young Malevich saw live artists. Moreover, he witnessed the creation of religious paintings in a church. His father did not in the least share the son’s admiration for painting. He envisaged a career in sugar refinery for his son, thus he immediately sent him to the village of Parkhomivka, where the boy was supposed to learn a “real” trade. After successfully completing a course at the local agrarian school, Malevich was loath to follow his father’s career, which seems to the 15-year-old so far from the outburst of colors in a Kyiv shop window.

But fate was benevolent to Malevich, and he comes back to Kyiv with his family, to settle in a suburb. Another gift of fate was his mother, who keeps her son’s passion for the arts of painting and embroidery secret. She presented the boy with a box of paints, which became an indispensable part of his everyday life ever since. Malevich tried his hand at painting, and frequently attended Mykola Murashko’s well-known studio in order to learn the craft better.

Later, the Malevich family had to move again, this time to a small provincial town of Kursk. There Malevich gets married, but he spends all his free time painting. He was even able to organize a little club together with his companions, but he had less and less time for art.

Despite severe daily routine, Malevich decided to take up art seriously, therefore in 1904 he moved to Moscow. However, an impulse alone was not enough: several times in a row he applied to the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, but in vain. Yet the untiring artist would not give up and started attending classes at Fedor Rerberg’s studio. Rerberg also helped the persistent young man to exhibit his canvases.

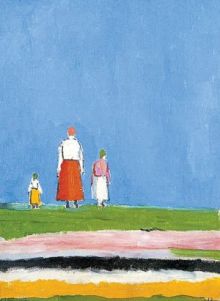

Open to new ideas, Malevich finds himself among Moscow’s avant-garde painters. He meets Wassily Kandinsky, who exerted perhaps the strongest influence on his choice of career in art. It was Kandinsky who introduced Malevich into the Knave of Diamonds art group. As early as in 1912, the young painter exhibited his works. The most prominent piece is Peasant Woman with Buckets and Child, which reflects Malevich’s Ukrainian roots. The landscapes are naive and pure, shimmering with golds, crimsons, and greens, and the simple, clear forms are reminiscent of Ukrainian icons.

Malevich would often mention his admiration for icon painting, and considered it to be the best, most perfect form of art. The rural cycle would not have been complete without his Ukrainian landscapes or icons, which have always been an indispensable element of a Ukrainian interior. These canvases, which had departed from realistic precision and approached the esthetics of cubo-futurism and primitivism, echo with notes of the future innovative style. The vivid, expressive figures of peasants, almost square haycocks, triangular and rectangular fields would soon transform into mystic shapes of squares and crosses, devoid of a slightest hint at earthly reality. Paradoxically enough, Malevich’s non-objective painting was shaped under the influence of the “living objectness” and immediate vitality of traditional Ukrainian culture.

For Petersburg public, the avant-garde exhibit was a challenge to common sense and morals. The audience felt fooled, seeing the primitivism and vulgarity of the canvases which were an overt mockery of the visitors’ intellectual abilities. However, Malevich and Co. were far from attempting to annoy the public, although they unwillingly accomplished a true avant-garde beau geste, shrouded in shock and scandal. Nowadays most of the paintings from that exhibit, which are kept at the museums of New York and Amsterdam, evoke neither overreaction nor mental turmoil.

Later, despite various manifestations of his talent, Malevich would not give up his attempts to upgrade art and put it on new tracks in life. In 1915, the artist displays a few of his abstract paintings in the exposition “0.10” in Petrograd (St. Petersburg). In an inconspicuous corner, next to other pictures, sat the world-famous Black Square, awaiting for its moment of glory. It is considered to be the herald of the new trend, known as suprematism. Malevich used this notion to outline the dominance of certain colors over the others, which stipulated the absolutization of the “pure sense” of the world.

His other canvases were also displayed: Black Cross, Black Squares on White, and Red Square, which especially looked as if it had been copied from peasant garments of his early cycle. The graphic squares on white canvas, with their deliberately uneven edges which rendered the vibration of the paintings, suggested nothing other than Ukrainian freshly ploughed black-earth fields, as dark as night. Malevich would himself refer to abstract, suprematist “texts” as to vast plains, embracing everything around. The artist had indeed destroyed the ring of the horizon, but he left the sense of the powerful and endless world. Malevich began to actively implement his ideas as he gathered a school of his supporters. Another no less famed painter Marc Chagall invited him to teach in Vitebsk, Belarus, where Malevich applied his methods. But teaching in Vitebsk did not last long, and the theoretician of suprematism had to return to Moscow. The public there was more and more open to his avant-garde experiments, yet the regime kept a close watch on the painter. He continually felt that pressure and missed the Ukrainian province, where surviving was not an issue, and the openness and kindness of people were so inspiring. Obviously, the artist longed to break the iron ring of persecutions and, like most talents, dreamed of Paris, his favorite Fauvists, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Paul Sezanne, who had had a strong influence on Malevich. After all, he craved for freedom of spirit.

If not for an invitation from the Kyiv Art Institute in 1929, Malevich would have virtually suffocated in the Moscow vacuum. In Ukraine, his avant-garde paintings are highly appreciated, thus he exercised a considerable influence on cubism and futurism, and not only in painting, but also in literature and cinematography. Yet this was not what mattered for the artist. At last, he was able to leave the city and go to the country, into the quiet space of his childhood and his inspiration. Suddenly, the painter returns to (or rather completes) his “rural cycle,” which opened his career. A bright example is his Reapers (1930), which is now kept in St. Petersburg.

His second “rural cycle” continues the themes of loneliness, which permeated all his stylistic quests. Quite unexpectedly, a motif of humanity pops up. The artist was often censured for the propaganda of village chores. But although he was forced to play by double standards, he never betrayed Ukrainian themes and his key esthetic principles. The picturesque countryside, the patterns of fields and landscape, reflected in his mother’s embroidery, and the hardworking and kind Ukrainian character would always remain prototypes of Malevich’s mysterious avant-garde.