In our time of gadgets and social media, any loud statement reaches the other part of the world in a matter of a second. Any one of us can become friends with a foreigner and learn how his compatriots view Ukraine. However, several centuries ago the way to any foreign country was long, difficult, and costly. So the public opinion about some or other territories was shaped by the artists, writers, and cartographers. The employees of the National Museum of Ukrainian History made a cross section of the ideas the foreigners used to have about our territory in a way of an exhibit “Through the Eyes of Near and Far Neighbors: Ukraine in Graphical Works of the 17th-19th centuries.” It was compiled with the assistance of Ukraine’s National Museum of Art and the Vernadsky National Library. The most of the items from the funds of the abovementioned institutions are on display for the first time.

COSSACKS ON THE BOOK PAGES AND MAPS

The curator of the exhibit, senior researcher at the National Museum of Ukrainian History Yaroslav ZATYLIUK starts the exhibit tour with the first sources of information about Ukraine for Europeans. In 1517 a scholar from Krakow Maciej Miechowita published Tractatus de duabus Sarmatiis (“Treatise on the Two Sarmatias”), which, in particular, mentions the Ukrainian lands. “It’s shaping the first stereotypes about the fertile ‘land of milk and honey,’ which seems to be historically cursed, because these borderline lands are all the time facing the risk of invasion and ruinations,” the curator of the exhibit explains. The information from this treatise and other Polish chronicles was used in the famous European encyclopedia, The Cosmographia (“Cosmography”) by Sebastian Muenster in 1556. There is small book from the “Republics” series with the description of Polish, Lithuanian, and Ukrainian lands lying next to these books at the show-window.

The first more or less full description of Ukraine in the 17th century was accomplished by the French engineer and cartographer Guillaume Levasseur de Beauplan. During his 20-year-long work on our territory he created the first general map of Ukrainian lands and topographical plans of some of its territories. These accomplishments are still used in the European atlases. The perception of Ukrainian territory as a separate Cossack state is supplemented by the maps created by outstanding German cartographer Johann Baptist Homann in the 18th century.

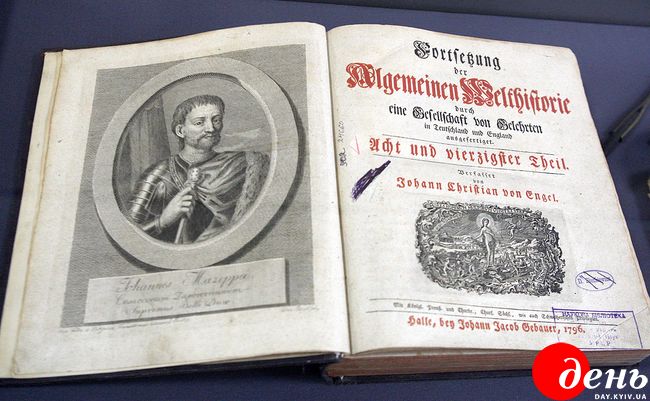

“The interest to our lands has significantly increased during the Enlightenment,” Zatyliuk continues, “It was stirred, in particular, by Voltaire’s History of Charles XII, which was published up to 100 times in different languages. In this book the author describes the Cossacks and Mazepa, Charles’s wandering across Ukraine, he dwells on the reasons of Swedes’ defeat in their war against Russia.” At Napoleon Bonaparte’s order the history of Zaporozhian Cossacks was researched by French historian Charles-Louis Lesur in his work The History of Cossacks. Johann Christian Engel’s book written somewhat earlier is one of the first works on Ukrainian history. Interestingly, they were used as a reference by European, some Russian and Ukrainian historians, in particular, Dmytro Bantysh-Kamensky, whose notes about his journey from Moldavia and Valakhia are also on display at the exhibit. Such descriptions with accompanying illustrations and maps were very popular among the travelers of that time. For example, the exhibit features the German travel notes dated 1855, describing the climate, the soil, the natural recourses, as well as the folkways of the Ukrainian peasants.

A SEPARATE ETHNIC GROUP

The texts and several maps are rather a supplement to the exhibit, its main powerful and expressive visual element. Yaroslav Zatyliuk tells about the perception of Ukrainians and their settlements, making references to the items in front of us. “On the verge of the 18th and 19th centuries Ukraine was perceived like a not enough civilized borderline territory with patriarchal behaviors and rich history, which was not completely cognized by the population. The image of the Cossack nation has been replaced by their descendants, peasants suffering from the Moscow despotism. The task of experienced Europeans is to bring here the achievements of civilization,” the researcher explains. “The Russian travelers came to Ukrainian territory to see the historical monuments from Rus’ time and research their ancient roots. They thought the Cossacks, and especially peasants, were a separate ethnic group which had nothing in common with the princes. In fact it’s not something new to the world history. In that time Europeans stuck to the opinion that their contemporaries from Greece had no relation to the ancient heritage, considering that the French, Italians, etc. had much more in common with the heritage of the ancient state.”

The attitude to Ukrainian people as a talented one, but lazy in terms of state governing, hence captivated, can be traced in the landscape engravings. No matter where we find ourselves, when we look at the pictures, whether in the Stryi raion, Kyiv environs, or Poltava oblast, everywhere the emphasis is made on the incredible landscapes and impressive monuments. Both Russian artists, and Napoleon Orda, who considered himself a Pole, depicted the meadows and woods, churches, houses, and palaces, built by the rulers. But every one of them focused on what referred to the history of their empires, the Russian empire and Rzeczpospolita, correspondingly. The tiny figures of the peasants busy with their everyday chores are making the foreground scene more detailed.

A separate wall in the exhibition is dedicated to human portraits and depiction of traditional Ukrainian clothes which make up the image of the peasant nation. Mykhailo Klodt’s works depict the life plots and beautiful relaxed people wearing bright clothing. The etchings and the portraits of the peasants by Lev Zhemchuzhnykov as well as the sketches by Kateryna Haltseva depict the peasants in everyday life, but they look more mundane. Dominique Pierre de la Flise, the author of the ethnographic description of the peasants of Kyiv gubernia added to its huge volume an album of five pages and pictures of their costumes. One can see part of them under the show-glass. This collection cannot but include Taras Shevchenko’s landscapes and several etchings, the fragments from Picturesque Ukraine. For him this project was the means of presenting Ukrainians in the best possible way. Unfortunately, in spite of the big intentions the project was never finished.

MAKING THE MOMENT STOP

We should pay the due both to the artists depicting the Ukrainian lands and those who have managed to preserve the treasures. For many items of this exhibits show to us the monuments which have already disappeared (for example, the khan tombs in Bakhchysarai) or look absolutely different (same old Podil and the works by Ivan Hryhorovych-Barsky). The exhibit includes also the Crimean landscapes dated 19th century, such as the Sudak Valley, Alushta, and Simeiz.

In the center of the museum hall there is a huge photo of the Mykolaiv chain bridge, the first capital passage across the Dnipro in Kyiv, which existed in 1863-1920. It was taken by John Cooke Bourne. Bellow, for comparison, there are lithograph postcards made at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, with the same cityscape. “The means of depicting reality are changing with time,” Yaroslav Zatyliuk finishes the tour, moving the stationary magnifier on the glass. “Long time ago this photo was very expensive. It was difficult to make. Now nearly all of us are carrying Smartphones with cameras and several gigabytes of digital archives.” So, every one of us has an opportunity to create not only images of our own, but also the image of our city and state in the eyes of the foreigners. But this ease comes with the additional responsibility. Of course, Photoshop is powerful software, but it’s a more complicated challenge to bring the reality closer to an ideal image rather than its imprint in the camera matrix. And it’s much more interesting.