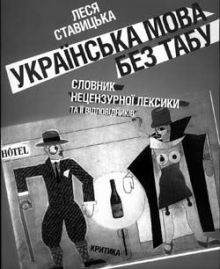

What should have happened long ago has finally taken place. Kyiv’s Krytyka Publishing House has published the book The Ukrainian Language without Taboos: A Dictionary of Uncensored Vocabulary and Corresponding Words, or, in simpler words, a dictionary of Ukrainian obscenities and brutal language.

One can work at composing odes to the chaste Ukrainian language that resembles the song of a nightingale, cursing “zombie slave” and “fifth- columnists,” who are vilifying this resemblance to a nightingale’s song. But a language is a living organism, and its every part is needed for the normal functioning of the whole. Attempts to cut off one of these parts are by no means helpful for the revival and flourishment of the language that professional Ukrainians are so anxious about.

The Ukrainian Language without Taboos is a unique publication in many respects. This is the first academic study of Ukrainian obscene language performed. This is no surprise, because Krytyka is known not only for its thorough scholarship and excellence of its publications, but also for its intellectual innovations and discoveries of unexplored subjects.

The new dictionary is a journey through the very kind of Ukrainian about which you’ve always wanted to know, but were afraid to ask. There is a comparatively small number of “these words,” but even they are components of extremely witty, rich, and apt expressions. Much of that can be quoted on a newspaper page, but still it would be better to peep inside a dictionary. Any unbiased admirer will be overjoyed: nearly 5,000 words and idioms, etymological references and historical-cultural commentaries, and examples of non-standard usage. This is a truly lively — controversial, edgy, energetic, incredibly funny — and beautiful language.

The author of the dictionary is the professor of philology, Lesia Stavytska, who heads the Department of Sociolinguistics at Institute of Ukrainian Language of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. She is the author of a number of linguistic monographs, such as Esthetics of Speech in Ukrainian Poetry of the 1910s-1930s (2000), Genres and Styles in the History of the Ukrainian Literary Language (1989, co-author), and the sensational Brief Dictionary of Jargon Vocabulary of the Ukrainian Language (2003). Below is our interview with the researcher about her new book, which will probably spark even more acute discussions than any of her previous works.

Let’s talk about etymology. From where did obscenities enter the Ukrainian language? It is commonly held that our language is extremely chaste, and all obscenities are social borrowings from the Russian or even the Tatar language.

“This is an absolute myth, and I write about this in a detailed way in the preface. In approximately 1865 Russia published The Emblematic- Encyclopedic Dictionary of Tatar Obscene Words and Phrases. The characteristics of the vocabulary and phraseology included in the dictionary as ‘Tatar’ words are connected with the fact that this meant ‘any non-Christian,’ ‘strange’ ones. This is no surprise because alien national things are associated with something bad in the everyday ethnic consciousness. In other words, since these were bad words, the vocabulary title qualified them as if they were (Mongol)-Tatar, i.e., strange, unnecessary, and obscene. Since that time this reputation has stuck to them. And this myth has turned out to be very enduring: to this day people consider that all this was brought into our language by the Mongol-Tatars. By the way, the Ukrainian saying ‘to swear like a Muscovite’ (to use bad language) has the same nature, because bad words are attributed to Russians, which enables us to keep away from them and the Ukrainian language to look better and more decent.”

Where did these words come from?

“All the words that we are accustomed to calling ‘obscenities’ indeed originated from the primitive Slavonic language, and they initially did not have any primitive meaning. Their etymology is innocent, but since the culture has a ban on the lower part of the body, the words denoting the lower part of the body and its function correspondingly grew obscene.”

As far as I know, this dictionary was born of not always adequate acceptance of your Dictionary of Jargon Vocabulary of the Ukrainian Language, published in 2003. Where did the problem lie?

“As soon as the dictionary of jargon appeared, most readers immediately accepted it as a dictionary of foul language, obscenities, and for them this was a breakthrough in the chasteness of our language. It contained neither obscenities nor their derivatives except for several words. Because of my oversight (I repent!) there was sexual slang, but slang is a euphemism for an obscene word to denote the human sexual sphere. I guess that the interpretation itself could give the impression that this is a dictionary of foul language. Articulation of the sphere of the lower part of the body, be it conducted via normative language, but embodied in a written way — because for our people everything written has a sacred content — has apparently caused this sort of reaction. When I talked to journalists or took part in a talk-show, they first of all saw a verbal ‘strawberry’ in the dictionary of jargon. Of course, when they were flipping through the pages, they did not find what they wanted to see, although they wanted to very much. Then they started to provoke me in various ways so that I would utter a rude word. I got very tired of explaining the difference between the jargon language of computer programmers, drivers, schoolchildren, pupils, and foul language. I had to sit down and write the sort of language that consumers of lexicographic publications were missing.”

What sources did you use?

“I knew that there were lexicographic collections of foul language in the Slavic world and American culture. I had studied works by Poles, Czechs, Serbs, and the vast American experience. I compiled the dictionary, involving, of course, folklore and all accessible sources that could illustrate the obscene and also erotic space of the Ukrainian language.”

Could you give us a few details about folklore?

“This was mostly Ukrainian scandalous folklore, which is extremely rich, interesting, and regionally and conceptually varied. For example, we have the bawdy folklore of eastern Ukraine: editions that were prepared for publication by Mykola Sulyma and Mykhailo Krasykov, and somewhat different in spirit, Transcarpathian Rusyn folklore: Rusyn Eros and Transcarpathian Kolomyiky. I also used lists of oral expressions that people gave to me and I recorded them in Kyiv, Poltava region, everywhere I had an opportunity to go. I am fully aware that the dictionary can be much broader even in terms of exclusively oral language, but many decades would be needed to do this. I constantly have new ideas for dictionaries. My scholarly conscience is telling me about the urgent need to create a dictionary of Ukrainian colloquial language, non- obscene Ukrainian abusive language, and translation dictionaries.”

Speaking about translated and borrowed words, one cannot deny that some absolutely literary words are of foreign origin: adulterer, Alfonse, etc. Should they be in your dictionary?

“It is admitted in the preface that the dictionary embraces not only obscene words but also euphemisms and sexual expressions. There is the lower part of the body as well as its corresponding semantic field and euphemisms; there is vocabulary that is close to obscene. By the way, the dictionary of sexualisms should be a separate work, including both specific Freudian terms and psychoanalytical notions. For The Language without Taboos I chose only words referring to the reproductive function, sexual relations, and the human erotic space.”

Continuing the literary theme, I noticed that you quote a lot from our contemporary literature?

“Yes, I do. This is thanks to the burgeoning of Ukrainian literature that began in the 1990s. The word has become a deed, resistance to the system, and artistic ideology. Whereas I omitted the obscene layer in the dictionary of jargon, here it is presented on a maximal scale: contemporary texts written both by women and men, and partially the literature of the 19th century was taken into account. But I have not succeeded, unfortunately, in embracing all of foreign literature in translation, which also has this powerful linguistic range, for example, Elfriede Jelinek’s Die Pianiste in Ukrainian translation. This is also a very important source that will supplement future editions, and the dictionary might have a somewhat different image.”

Which of our writers use obscenities in a most active way?

“It is difficult to name a single author. This type of usage of this type of vocabulary is in one or another way assimilated with the writer’s style, esthetic-pragmatic aims, communicative strategies of the characters, and definitely the writer’s conceptual attitude to the world in general. Yurii Andrukhovych’s style, his irony and self-irony assimilate the ‘illegal’ language. I like his Taiemnytsia (Mystery), where obscenity incorporated into reminiscences of the Soviet reality, in which he was formed, or into the personal intimate sphere, makes the emotional hubs of his relationships with reality more expressive. Serhii Zhadan has a different esthetic of bad language. His hero wants to come to terms with the help of obscene language, to conciliate two worlds: the world in which he lives, the intimate microcosm and life with its ‘clinical boorishness.’ We see him responding to life, to its insolence, the unfairness with a soccer goal, behind which is the metaphysics of bad language in general. Rebellion can be expressed through deviant behavior (physical violence, alcohol abuse, and suicide) or poetic invective, but one can also swear with taste in a rude way. Even if anyone has sworn at least once in his life, this may excite the curiosity of both writer and linguist. Along with that I will say that I very much enjoyed reading the interview-book by the ‘sacred monster’ of French music-hall art, Serge Gainsbourg; He is totally epatage: in his natural and anti-natural sexual aspirations, his views of women, the world, in his way of decorating his own house, etc. His obscene language serves only as an incrustation of the true and sincere expression of own ‘Ego,’ therefore his interviews do not leave any feeling of disgust, even if the question is bestiality. As for writers, everything depends on their talent. If a writer is gifted, the reader may not even notice this bad language because it will have a notional and emotional stress. If a writer has no talent, obscenities beaded with commas will only irritate, and they will be a cheap surrogate of a real dramatic effect or the tragicomic nature of life.”

We are speaking about people who started writing in the 1980 and 1990s. What about the older generation?

“Those texts that survived until our time were, of course, well-edited and censored. But I recall the personality of Mykola Lukash. As a translator, a man with a brilliant feel for language, he felt that language cannot be castrated, and he wrote a number of brilliant obscene epigrams that were included in Shpyhachka, which was published in 2003. His Matiuholohiia was destroyed after his death so that it would not disgrace the writer’s memory. Here it would be appropriate to mention the bawdy folklore that was collected by Volodymyr Hnatiuk and published in 1912 in Leipzig under the title Fables Not for Publication (the text was written in the Roman alphabet). This book is now a bibliographic rarity, but our publishers are in no hurry to re-publish it. Although this book has not been republished, some of its materials are included in contemporary collections of Ukrainian anecdotes without even mentioning the man who had once put titanic efforts into publishing a collection of original erotic stories abroad. As far as I know, the Russian publishing house Ladomir will be issuing Hnatiuk’s Fables Not for Publication: Ukrainian Bawdy Folklore. So Russia is publishing it, but our publishers are not interested in this sort of literature. However, this may be explained by the fact that obscenities have always been part of Russian culture. That is the reason why Barkov and Pushkin are reprinted as well as Cherished Fairytales by Afanasiev, Lermontov in the series Russian Undercover Literature. But as I have already said, Russia has a different cultural background for this sort of literature. Life and the book market are forming awareness, and awareness produces language. If obscenity and eroticism were part of the national discourse, there would not only be a different attitude to obscenity, but the appropriate discourse practice would have formed. Bans will never eradicate undesirable things. In the case of bad language, one can speak about a double taboo: this is first of all words tabooed in a denominative way. We drag in the Russian language here, saying the damned Muscovites brought it. Imagine how strong the temptation a man has, when he does this on a regular basis, to overcome this double taboo. And a Ukrainian, eager to swear, will do this in Russian, and will find great relief. I think that along with us becoming democratic, civilized, and experiencing a deep inner freedom, the obscene vocabulary will disappear as epatage and will probably start harmonizing with some new sides of inner freedom. Let us see which literary generation will be born next and whether it will be free, and what will be the lexical markers of the world of its discourse.”

On what does it depend?

“On the spiritual climate in society. On the one hand, bad language is pandemic. On the other, there is such a hypocritical innocence, such an inner non-obscenity that it reaches the point of homophobic Marches for Moral Purity. Our society remains deeply patriarchal. Look at our secular chronicles. How is epatage constructed? A make of a car, clothing, gold cell phone, several hundred meters of apartment in Kyiv. People say that this is an epatage program. These programs are interesting as the discourse of glamour, as a linguistic and social marker of celebrities; this is the way they call themselves, not epatage. When our society becomes wealthier, instead of discussing how many thousands of dollars a purchased suit cost, another category of epatage will emerge, which is free, unpredictable, and attractive. A person has to be free in his/her passions and lifestyle, which may differ from all the rest, but not violate the legal norms and freedom of another person. But society should evolve to reach this.”

You are speaking about the pandemic spread of bad language. Perhaps this is for the best, a sign that our language is alive and becoming freer?

“Obscenities are not the only attribute of the living Ukrainian language. When the language was, as you say, enslaved, despite this everyone who swore in Ukraine continued to do so, like those who are still swearing in Russian. The language will be free only when Ukrainian reigns in the information space, when FM radio stations talk in Ukrainian, when films and serials are released in Ukrainian, when a Ukrainian literary work wins the Nobel Prize, conditionally speaking, of course.”

Speaking about society, whom do you see as readers of the dictionary?

“It is difficult for me to predict what kind of readers the dictionary will have. On the Web site “Atheism in Ukraine” an opinion is being expressed that ‘Lord bless me,’ ‘God, forgive me,’ and ‘chapel’ are used in an erotic sense. However, this turning upside down is absolutely natural because it is a carnival game mentioned by Bakhtin, where the sacred becomes profane. Therefore, everybody reads according to his/her own point of view. Some people are interested in euphemisms, others — in brutal language. Students, scholars, lecturers, journalists, and average readers... But I will see everything after reactions start coming in. The life of the dictionary of jargon was very stormy, so I am very curious about the reviews, wishes, and even reactions that I may not even be expecting.”