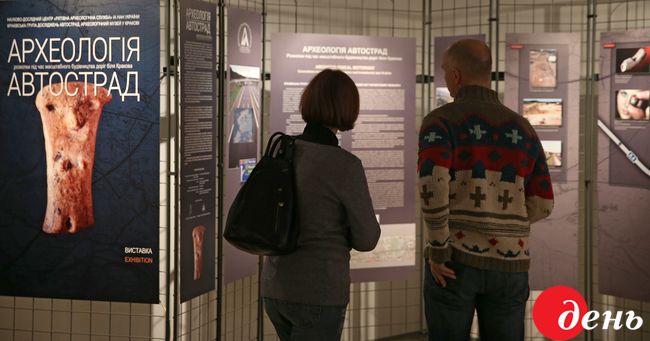

“We have a highway in Kyiv – an archeological one so far,” Jacek Gorski, director of the Krakow Archeological Museum, said, opening the exhibit “Archeology of Highways.” He specially arrived to attend its opening at the National Art Museum of Ukraine.

14 YEARS OF WORK, OVER 170 SITES

The project is called so because it gave an impetus to archeological research which resulted in an exhibit that is very far from the historical science – the construction of a highway. Deciding to lay the A-4 section that links Krakow with Tarnow and passes through one of ancient Europe’s most populated areas, the Poles did not forget about their historical legacy on these lands. Accordingly, they set up the Krakow Group of Highway Research which carried out “rescue research during the construction of the A-4 in Lesser Poland voivodeship.”

This rescue research was really of a large scale: 14 years of work, over 170 archeological sites with a total area of more than 200 hectares, with items dating back to the Upper Paleolithic. Gorski emphasizes: “It was possible to achieve a great success in these large-scale archeological explorations only because three centers of archeology – the Jagiellonian University’s Institute of Archeology, the Institute of Archeology and Ethnography of the Polish Academy of Sciences, and the Archeological Museum in Krakow – made a joint effort and reached agreement.” It is a rare occasion indeed when two roads – a highway and a historical path – were being built at the same time.

THE PAST IN TODAY’S VERSION

As if to emphasize the rightness of this approach, fate presented archeologists with a happy find – a treasure from Aleksandrovychi, which dates back to 800-700 BC. It includes about 50 decorations: bracelets, hairpins, pendants, buttons, and breast collars. What is more, these items are not local – they come from the remote areas of Northern and Southern Europe. Scientists believe it is the treasure of a family that was placed high in the hierarchy of that society.

Yet this is not the oldest monument displayed at the exhibit. An ancient village aged 7,000 years was found in Brzezie, east of Krakow. Remnants of 26 so-called long houses with a brushwood superstructure were found. Polish researches even reconstructed such a house by means of computer technologies, which you can also see at the exhibit. For one more particularity of the “Archeology of Highways” is that the past is presented in a modern way here. In addition to objects, such as vessels, decorations, etc. there are a lot of computer and photo reconstructions of people, weapons, houses, wells, and potter’s ovens.

Natalka Voitseshchuk of the Rescue Archeological Service, curator of the exhibit in Ukraine, outlined the importance of “Archeology of Highways” as follows: “The exhibit is greatly valuable because every spectator can not only see a found object, but also read its history and the interpretation of archeologists. These objects ‘revive,’ for we can learn where they came to Krakow’s outskirts from and how they were used. Thanks to Polish archeologists, we can also see reconstructed settlements and clothes of the ancient inhabitants of Krakow’s outskirts and have a clear idea of the way people lived thousands of years ago.”

“THE MAJORITY SEE ARCHEOLOGY THROUGH THE PRISM OF ‘INDIANA JONES’”

Another important detail: this exhibit also plays the role of a photo report on how the excavations were carried out. Yet, as Oleh OSAULCHUK, director of the research center “Rescue Archeological Service” of the Institute of Archeology of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, emphasizes, they failed to record everybody and everything. “This exhibit is a fruit of the hard and invisible work of dozens, hundreds, of Polish archeologists. They are not always on photographs. That’s why the majority see archeology through the prism of ‘Indiana Jones,’” Oleh says.

The exhibit thus raises another important question: what does the work of archeologists really consist of? “On the day the exhibit was opened, I had an opportunity to hear a very interesting expert discussion at a roundtable with participation of Ukrainian and Polish specialists. I am glad that this discussion made it possible to exchange opinions, particularly about various problems archeologists come across in their work. It is very important to exchange experiences,” Emilia Jasiuk, an advisor to the Polish ambassador to Ukraine, said.

Indeed, “Archeology of Highways” has seen 16 Polish cities since 2011 and was shown in Lviv last year. It is going to Poltava and Dnipro soon. The exhibit can be an excellent occasion for a joint discussion, exchange of knowledge, and cooperation between Ukraine and Poland. As a representative of Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (the exhibit is being held in Ukraine under the auspices of this ministry and the Embassy of Poland), pointed out, it is one of the ways of cultural diplomacy. This dialog is also of great importance to the National Art Museum. Its director Yulia LYTVYNETS confesses: “We were looking forward to this international project. It is rather symbolic for our museum which used to be archeological. Now, more than 100 years on, archeology is on our premises again.” So this exhibit arouses not only Polish, but also Ukrainian history.

ETHICAL DUTY TO SOCIETY

In general, “Archeology of Highways” convincingly proves that history is right beneath our feet. One can just incase it in concrete, due to laziness or the wish to grudge money for research, and create something run-of-the-mill, of which there are thousands in the world. But one can also take a longer way – touch the depths and uncover the secrets of our own past. This will result in unique objects which, incidentally, specialists and the public are only beginning to discover. For several more volumes of the “Via Archeologica” series launched by the Krakow Highway Research Group are to be published shortly. Only then, as Polish researchers point out, will “the group do its moral duty to society.”

As for us, all we can do is hope that this approach will be also taken to Ukrainian historical objects, particularly on Poshtova Square in Kyiv, and they will show the world a more that a thousand-year history of the Ukrainian state.