On the one hand, the oeuvre of this female author has always been in the focus of researchers, readers, and cinema and theater personalities. For example, her Zemlia (Land), U nediliu rano zillia kopala (On Sunday Morning She Gathered Herbs), Vovchykha (The She-Wolf), Valse Melancolique, and Tsarivna (The Princess) have been staged and screened, and they are part of school and university curricula. Chernivtsi honors the famous writer’s memory twice a year, and national-level celebrations are held on jubilee years.

On the other hand, it was not until 1991 that Olha Kobylianska’s last novel Apostol cherni (The Apostle of the Rabble) on which she had worked for about 30 years was published. When this novel came out, the writer IrynaVilde called Kobylianska “apostle of the idea.”

Mykyta Shapoval, an Ukrainian literature researcher who lived in Prague in the 1920s-1930s and prepared Apostol cherni for publication, wrote to Kobylianska, “I kiss the hand that wrote The Princess (one of Kobylianska’s first novellas - Author) and is now writing... the prince.” He meant the protagonist of the novel Yulian Tsezarevych.

What scared Soviet literary critics in this novel so much that they stooped to outright deception, claiming that Kobylianska’s talent “fell behind the horizon” in the 1930s and she wrote nothing that matters? Apostol cherni is interesting to read. It focuses on the destiny of a Ukrainian intellectual, the son of a watchmaker, who studied, worked, was passionately and selflessly in love, traveled, and defended his right to live and think in his own way. He eventually became a military serviceman. The writer’s pen describes equally well the characters’ sentiments and the amazing pictures of surrounding nature.

Yet the writer focused in this work not on the destiny of certain heroes, such as Natalka Verkovychivna in the novella Tsarivna, or on social problems, as she did in Zemlia and many other novellas, but on such things as Ukraine, statehood, and nation. This is what the Soviet authorities and literary critics could not accept in Apostol cherni in spite of the work’s high artistic level.

The novel came out in Lviv in 1936 and was part of Kobylianska’s personal library (now it is kept at the Chernivtsi-based Olha Kobylianska Literary and Memorial Museum). Meanwhile, this work’s first Ukrainian publication in Bukovynski Zhurnal was prepared by the researcher Oksana Ivasiuk on the basis of the copy that she brought from... Canada. This provided an impetus to a true ideology-free study of the life and works of this prominent writer, who was widely known in Europe and America, not only in Ukraine, still in her lifetime.

The novel was soon published as a separate volume in Ternopil and then in Kyiv.

Then came a new generation of academics who decided to read Kobylianska anew, with due account of modern achievements in literature research. Among them is Yaroslava Melnychuk, a young lady from Chernivtsi. She set herself a goal to prove that Kobylianska is not only “a late 19th-early 20th-century writer who made a considerable contribution to Ukrainian literature in the next few decades.” The researcher achieved her goal in the book Na vechirniomu pruzi (In the Twilight), in which she scrutinizes the least known stage of the writer’s creative life-1914 to 1942.

Kobylianska worked as hard as she could for 28 years. She penned antiwar novellas, such as the psychological masterpiece Lyst zasudzhenoho voiaka do svoiei zhinky (A Letter from a Convicted Soldier to His Wife), as well as morality and ethics stories, such as “Ohrivai, sontse!” (Warm Be the Sun) about the bitter destiny of a woman who killed her drunkard husband in despair, which only cost her a court sentence, instead of solving her problems.

Kobylianska also worked as a critic: she wrote a thought-provoking literary essay on Leo Tolstoy, one of her favorite writers. She described Bukovyna folk customs and rites in many novellas she penned in the 1920s.

Analyzing all that Kobylianska wrote in this period, including Apostol cherni, Melnychuk notes that she also focused on such a typical Soviet-era phenomenon as falsification of authorship.

A feminist activist in her young years, Kobylianska contributed multiple articles on this subject to Ukrainian newspapers.

In the last period of her creative life, she also contributed to newspapers, and all the Bukovyna Ukrainians were thirsty for her word. As this region was under Rumanian occupation at the time, Kobylianska was for her fellow countrymen the symbol of a revolt against circumstances. There are still people in Bukovyna, who recall, as the brightest moment of their lifetime, the Shevchenko soiree held at the People’s House in 1937, where they could see Olha Kobylianska. In Mykhailo Ivasiuk’s novel Conviction there is the novelette “Windows” based on the writer’s own life story: he says he once saw Kobylianska on her patio and looked at her, spellbound. The next day he sneaked into her study room and put a vase with flowers on the windowsill.

Soviet propaganda took advantage of the people’s unbounded love for Kobylianska in the 1940s by publishing newspaper articles under her signature. Melnychuk counted in her study that in just one year Bukovyna’s press printed 40 (sic) publications in three languages: Ukrainian, Russian, and Moldavian. The researcher is sure that these could not belong to Kobylianska, for the writer was gravely ill at the time.

Stepan Kryzhanivsky, a noted literature researcher who visited Kobylianska in June 1941, wrote, “Kouse Hnowing the writer’s condition and perusing the style of these publications, I will take the liberty of suggesting that they were written by some sharp journalists and then submitted to her for approval and signature.”

Kobylianska’s grandson Oleh Panchuk confirmed this, “Absolutely all of the 1940-41 comments ascribed to Olha Kobylianska in which she welcomes the establishment of the Stalinist regime in Bukovyna are downright mystification!”

Melnychuk offers convincing proof to protect Kobylianska from the ideological cheat ascribed to her, including the words of the writer herself: “I am no longer writing anything: my hand gave up on me, and I am not good at dictating.” She also analyzes the ideological and stylistic differences between the author’s authentic political writings and the articles that were ascribed to her. Besides, nobody could find at least some rough copies, preparatory notes, or autographs of those works-there is no trace of them in the Chernivtsi museum depository and in the manuscripts department of the NANU Institute of Literature. The researcher also catches the ghost writers making factual mistakes that Kobylianska could not have let slip, for example, saying Mamayivka instead of Mamayivtsi or calling the city Kitsman a village.

In the preface to Melnychuk’s study In the Twilight. Olha Kobylianska in the Last Period of her Creative Life, the noted scholar Ivan Denysiuk gives praise to the book: “This monograph opens a new chapter on Kobylianska.”

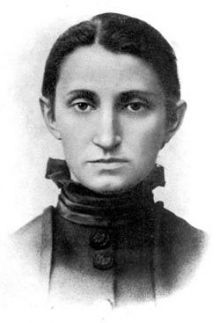

It is worth mentioned one more work about the famous Bukovyna writer on her birthday: the biographical novel Sharitka z Runhu (An Edelweiss from Runh) by Valeria Vrublevska, which depicts Olha Kobylianska’s life story on the basis of authentic materials. Her life was incredible. Born in 1863 and deprived of the opportunity to receive at least some systematic education, Olha spent a lot of time and effort doing routine house work. She suffered many heavy losses, including some in her private life. A petite and tender person, Kobylianska braved all the envy and taunts and became a great writer. Tsarivna, Valse Melancolique, Pryroda (Nature), and Zemlia are not just novellas about the bygone times-they are an interesting read even today, for they show full-blooded people with genuine feelings and, therefore, strike a chord with the readers.