A new personal album, “Vladyslav Shereshevskyi: Oeuvres” (ArtHuss publishers) has been presented as part of the Kyiv Art School project. In spite of hard times now, the artist’s ironic muse is not silent. She is laughing at Ukraine’s enemies and making everybody laugh together with her.

“I allow you to rub Ben’s nose,” Vladyslav SHERESHEVSKYI said. He even reduced his voice almost to whisper and, to look more convincing, rolled his eyes childishly. We had just said goodbye to each other after watching his “accounting” exhibit, “Dorobok 13-17,” at the Museum of Kyiv History. [“Dorobok” means “work, creation, oeuvre.” – Ed.] “Ben” was found almost in front of the elevator entrance on the third floor. “I deliberately applied two layers of varnish on his nose – let them rub it. You’ll see that money will come to you if you touch this nose.”

I could not resist bursting into laughter. Only he, Kyiv’s most ironic artist Shereshevskyi, could paint a classy portrait of Benjamin Franklin a la Joseph Duplessis (i.e. “like on a 100-dollar bill”) in his own unique manner and “reinforce” his nose in earnest because, while painting, he invented the lucky rub story.

YOU’D BETTER WRITE NOVELS, 2016

His bosom friends have long called him Sherik. Once you see his pictures, you recall his “classical” predecessors from various countries and centuries as well as Fedir Krychevsky, founder of the national school of contemporary art, and… Yet the oeuvre of the eternal enfant terrible of Ukrainian contemporary art Shereshevskyi is so citable, ironic, and self-ironic that it would be wrong to attach labels of any “traditions” in his presence. You feel that this looks funny. And you also look funny.

“It’s a splendid exhibit,” the artist says in his manner, “with the subhead ‘Alpha painting’ because what unites all the pictures is the wealth of painting. For practically everybody can see the humor, while about 70 percent of spectators can notice the second ‘layer.’ But, to assess precisely the painting…”

INFUSORIAN WITH SHOES ON, 2016

By contrast with Shereshevskyi’s previous major exhibit in the post-Maidan summer of 2014, what catches your eye at the current exposition at the Museum of Kyiv History is an almost total absence of the portraits of girls and boys wearing Ukrainian embroidered shirts and chaplets (they are replaced by variations on the theme of Degas’ ballerinas). In general, there are very few Ukrainian symbols on the new canvases. A somewhat ostentatious, albeit very sincere in the case of Shereshevskyi, painting patriotism has regained a more customary framework of playing with classics. On the other hand, political irony has grown into a true sarcasm.

“The ‘first layer’ of the perception of my works is humor and fun. But there’s a ‘second layer’ under it. Of course, I have paraphrases from classical painting. Here is Raphael’s Sistine motif. And here – a whole cycle based on the ‘great’ Vermeer. There are also Serov’s motifs, and so many other things. But the main thing is synthesis in the pictures. Owing to this combination, the funny may seem to be sad at the same time. Well, it is for those who are totally in the know,” Shereshevskyi says.

We walk along the exposition, and the artist tells me about almost each of his works. The striptease pole dancer, the heroine of the canvas with a “candy” name Kyiv in the Evening, turns out to be not only a symbol of today’s Ukraine. She is also painted against the background of a “variation” on a landscape by Kuindzhi, which Sherik says he painted over because “it was too beautiful.” The children with a baguette in hand on the picture Gift of Bread remind me of a classical canvas by the Russian realist painter Reshetnikov. Gogol’s portrait captioned as Our Gogol. The portrait of the Kyiv-born Golda Meir. “It is a generalized character, not a concrete volunteer battalion fighter,” the artist is trying to convince me. (“The ‘third layer’ in my pictures is when each of them sees their own things,” he adds hastily). Next to it are the mugs of drunken youths (In Contact). An elderly father with a rifle is going to war (Daddy, Don’t Shoot!). Working-class fellows with St. George ribbons are “culturally relaxing” at a vodka-laden table (Plebeiscite, Russia Today), and so on.

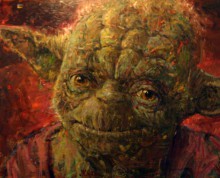

“I did Plebeiscite and Daddy, Don’t Shoot! when Crimea was being seized. Oriental Medicine was done in early 2015, when the eastern war entered an active phase, as was Russia Today. And here is SOS: kids in camouflage are sucking chupa-chups. It’s an antiwar picture – I am saying that it’s better for somebody to suck chupa-chups than to shoot,” Shereshevskyi comments. To clear the air, I ask about the background of the portrait of Star Wars’ Yoda who my vis-a-vis says has found his way to the exhibit by pure chance.

Realizing finally what kind of world rages outside the exhibition halls, we both lapse into silence for a while. Then I inquire whether his pictures “in response to the latest events” can be kept “for eternity.” And he answers, perhaps for the first time without irony: “You see, the Orange Revolution didn’t have much of an impact on me, as far as painting or interest in politics are concerned. But the latest [revolution] had a very strong impact. So I paint about what I am thinking, what worries me the most. I am sure it is ‘political’ painting that will remain behind in history. It is being created here and now by a person who is taking part in the events. This truth, this mood will never repeat. By the way, do you remember Still Alive, the picture I painted during the Maidan, which shows a smiling old woman with a Ukrainian wreath on? I was told the other day that it is now regarded in the US as an example of the Revolution of Dignity painting. Can you fancy that?” Sherik says, smiling shyly again.

I chose not to rub the nose of the oil-painted Benjamin Franklin, even though, of course, I lack money – like everybody and as always. But paintings are so nice here! You’d better come and see them on your own and feel happy. For it is for this purpose that Shereshevskyi creates his pictures.

The master’s works are exhibited at the Museum of Kyiv History until July 2.