This festival once again demonstrated that the widespread stereotypes about Ukraine as an eternally singing and dancing nation have a solid foundation. In this particular case the truism was justified not so much by number of participants (some 1,500 children, according to the organizing committee) as by the professional level shown by quite a few competitors. The Black Sea Games remains a launch pad for young talent, although it is anyone’s guess where that flight will take them. No one will tell you, not the organizing committee, not that office boasting a sign reading “Producer Agency,” not even all those gorgeous music television channels covering the event (provided you place several expensive commercials). The point in question is different. It has everything to do with singing, dancing, the sun, and the sea. Then perhaps we should start with the sea and the sun, leaving the dancing and singing for dessert.

EVERYTHING ACCORDING TO PLAN

The games began on July 7, with the indefatigable jury passing judgment for two days in a row, selecting performers worthy of being allowed onstage, the latter being traditionally located on the coast, a short walk from the sea. There was something profoundly symbolic about it all, a huge and heavy podium with a multitude of high voltage cables twisting their ways hither and yon, powerful audio and vide equipment, strobe lights bravely mounted on the Skadovsk beach. The whole thing strongly resembled a domestic show-biz situation, with this business surely dying yet struggling to hang on, painfully crying for mercy, attempting to assert its fading presence elsewhere in the world, while sinking slowly but surely into oblivion, with no one interested in finding out what exactly had happened and why.

As it was, a couple of dozen solo singers and nine “vocal groups” were selected by the jury. Appropriately, no names were mentioned before the festival and the jury consisted of Oleh Hrynchenko (composer), Ostap Stakhiv (US mass entertainment organizer), Ihor Dobrolezh (Green Records Studio producer), Valentyn Koval (M1 Channel producer), Karina (singer), Iryna Shynkaruk (singer), and Inna Vyshniak (BSG coordinator). At certain times during the festival some of the jury would be absent, others added, but this is the formal membership.

Friday July 11 turned out a bright day, as if specially to greet the festival (long before the sky was overcast, with frequent showers — and it would be the same after the event). In fact, all three days of the festival passed under clear sunlit skies. For the media people, the first working day began at the opening press conference, of course, where Dmytro Kryvoruchko, BSG Director General, expert in smooth round-about statements, declared, in stilted Ukrainian, “Right, everything’s according to plan.” He further informed that the jury had made an unprecedented decision whereby every performing group without exception would appear on the big stage, the one by the sea. There was no reason to try to find out why the jury made that “unprecedented decision.” After all, the kids were there, after going through pains of coming, so everybody was happy.

While selecting competitors, the jury arrived at yet another accurate conclusion; the younger groups were finally singing children’s songs. I mean their repertoire. Unlike them, the older ones had a problem with their repertoires, showing a bent for “grownup songs,” arrangements, and so on. Koval took a broader view: “It’s a global problem of Ukraine.” We don’t have songs, so what are we supposed to do? This problem also reflected itself in the terms and conditions of the contest; while previously the “matriculants” had to have two amateur songs (of three), for the past three years this requirement has slackened: now they needed only one. There are no songs nor money owned by young talent for which they could be marked off from the professional. Why are you poor? Because I sing. Why do you sing? Because I’m poor.

That same day, the traditional children’s parade marched along the thoroughfare of the children’s health- building center. Incidentally, the name of the street is Komunariv [Comunards Street] and there is still that bronze statue of Lenin in the center of the settlement, with his proverbial cap and outstretched hand clearly visible through the window of my hotel room. A Soviet Colossus from the former Soviet Colossus. Well, that’s the story... The parade looked quite attractive and cheerful. Everybody was happy to watch it, except the drivers being stubbornly waved away from the street by the State Auto Inspection. The winner of the festive march was the bright column of the Tavriya children’s camp. The prize to the inventors was eventually presented on stage by Neptune, an enigmatic man sporting a blue beard (it’s color being anyone’s guess why) who, with his artificial laughter in the mike (“Right, great, you’ve amused me!”) scared the younger age group among the festival participants — and not only them.

Incidentally, another question arose en route, having little to do with BSG as such. Why does Skadovsk have such an underdeveloped infrastructure and a beach which is, mildly speaking, lagging behind, complemented with a chronically polluted sea (owing to the concrete jetty, the coastline dividing the town and the seaport is buried under salty seaweed, the latter doesn’t rot but stinks a lot)? Why is all this while posing as Ukraine’s “children’s health center?” Who, for example, relaxes at Artek? Who owns it? Perhaps this situation is the same as that with all those Ukrainian music television channels and the distribution of submarines in the Black Sea (Ukraine has just one, a diesel-powered sub dating from the 1970s)? If we consider Skadovsk as being a center of sorts, what about the province?

Let us get back to the arts. The first day of the festival showed boys competing in the junior solo division, girls in the medium division, vocal groups, and a host of dances. The finals saw 11-year-old Artem Beleush (Kamianets-Podilsky) with his masterful rendition of [the Russian star Alla Pugachova’s] Arlecchino; 14-year-old Iryna Ushachyova (Krasny Luch) with her voice matching that of a mature Ludmilla Gurchenko, and the As Duet. The jury seemed to have overlooked Maryna Luchenko’s rather interesting vocal rendition done in Polish (placed second) and Nestor Luchko’s fiery folk-disco-rap mix.

Every concert had two emcees: Iryna Shynkaruk, the vocal star of the festival’s opening day, and Dmytro Yefymenko, remembered by the audiences for his open mouth, shouting “That’s great!”

NO BLIZZARD, BUT TSETSE FLIES BITING...

There were no fireworks at the opening ceremony, a shame. Perhaps one gets used to good things too quickly. Suspicions about the absence of fireworks were enhanced by the stage setting, instead of the regular vertical posters by the wings were painted versions of turtle castles (once again from sand...) The open secret was revealed at the closing gab session Sunday. They weren’t lucky with their sponsors. The organizers further admitted that it had an adverse effect on the prizes given to children. The farewell stand up buffet was also bungled — what was offered in lieu thereof is best not printed.

On Saturday the female emcee wore the pants she had on the previous night when singing. A Russian dance ensemble from Yekaterinburg, a guest star, performed three numbers. Once again the old idea of the international friendship of peoples was upheld onstage. Funny occurrences involving the emcees continued. Announcing the next competitor about to perform an Italian song and speaking Ukrainian, they pronounce the title of the song in Russian. What did that mean? That an Italian title can’t be translated into Ukrainian? This dubious approach held true throughout the festival; the name of the competitor and pertinent information provided in Ukrainian and the names of compositions (especially choreographic renditions) in Russian. One could only wonder why.

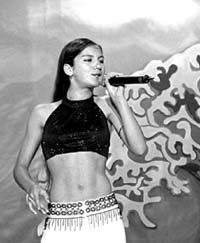

The girls performing as soloists in the senior age group were truly impressive. Especially Kleia (Valeria Kaluzhska, 16) from Donetsk with her original interpretation of a folk song, and Alina Starodumova, 16, from Odesa. She sang in English and her repertoire captivated the audience and jury. Each of the latter gave her five points, placing Kleia second.

That Saturday also presented an innovation in the BSG program, a brake dance contest involving three teams from Kyiv, Chernihiv, and Sumy. The whole thing looked very dynamic, as befitting the genre, including acrobatics, keen sense of rhythm, and Afro-American stunts. Something like that can be witnessed at the McDonald’s by the Khreshchatyk Metro Station. The number was started by four-year-old Tymofiy’s moving number involving his hands, legs, and above all a tail! In reality, everything had simply changed places. The battle of the giants of the spirit ended in the style of a children’s winning-friendship festival. Also, I understood that Zaporozhian Cossacks were the first bebop boys in dancing history; it suffices to watch the virtuoso pas from the famous Ukrainian hopak. It appears that break dance was actually invented by Ukrainians! And you keep saying that all we have managed is the pyramids and Stonehenge...

Among those making it to the finals were Andriy Kalizhuk, 14 (Donbas), the Lusterko vocal show group (Kremenchuk), and Harmoniya vocal ensemble (Krasny Luch).

Choreography was adjudicated by Oleksandr Leonenko (Meritorious Artiste of Ukraine, chief ballet masters of the Academic Drama and Music Comedy Theater of Mykolayiv), Tetiana Leonenko (soloist with the said company), and D. Kryvoruchko (director of the Tavriyski Ihry contest). As a result, the following performing groups were named among the finalists: Bravo (Odesa), Rassvet (Hola Prystan), Master Class (Kyiv), Oasis (Kherson), Blitz (Kerch), Dzhereltse (Makiyivka), and Radist (Kakhovka).

Yevheniya Vlasova was served for dessert that Saturday. Regrettably, the pop star had fractured her left little finger, yet she bravely did her job onstage, whirling like a little snowflake at a nursery morning show on Christmas Eve. True, her costume was anything but infantile; a dear friend of mine describes the skirts as short as broad belts. Proceeding from this year’s BSG context, her repertoire was thoroughly Russian, and the children received another year to understand the importance and vital need to master their mother’s tongue. True, in the end Vlasova “turned over a new leaf,” singing a Ukrainian folk song a cappella. Her motivation was great: After all we live in Ukraine, don’t we?

PAINTING THE SKY

Sunday saw the BSG finals, it was a night with a full moon, its silver disk rolling up in the sky, from right and upward of the podium, following its million-year route further across the sky, headed for eternity. There was a moon-glade and the vacationers [in the audience] seemed an inexplicable tremor of consciousness rooted in primordial history.

Inna Vyshniak shared her most intimate ideas with everybody: “My cherished dream is to see no parents in the festival audience. She might have a point there, as all [parents and] guardians thought their children were the best and wanted everybody to share their opinion — well if not everybody, then at least all of the jury.

The closing concert boasted grand renditions by the dance groups. In terms of genre there were six nominations, each with its own winner. The result was no first place in the folk dancing category, with Radist (Kakhovka), Chervona Kalyna (Kherson), Stylized Folk — Bravo (Odesa), Drive Synchron (the main thing for all to move the same way), Edelweiss (Odesa), Oasis Variety Dance Theater (Kherson, with their small dramatic love story), Blitz Variety Sports Dancing (Kerch, probably the first ever to perform better than the other groups) placed second. Oasis (junior group) and Dzhereltse (Makiyivka) made the show-ballet nomination.

I almost forgot to mention that BSG included the second international kite festive called Colorful Skies, its competitors representing Ukraine, Poland, Russia, and Belarus: 68 participants in all. The kites looked very attractive and the slogan sounded singular: Our Aim Is To Paint the Sky!

Marietta Ivanov, 7 (Kyiv), won the Golden Note for her will to win. The child had truly moved many [in the audience and on the jury], her fingers were too small to hold the mike, yet she asked the organizing committee what was more important, singing or competing. This kind of idealism becomes extinct as the years pass, when one understands that totally different things are required to achieve success.

There were actually two audience-choice prizes won by a charming duet made up of singer A. Beleush and Dzhereltse dance group. The Grand Prix went to Alina Starodumova, as expected. The jury’s decision was absolutely natural and understandable, as none of the competitors could challenge her mature and powerful vocal skill. In addition to the title and Golden Dolphin figurine, she was awarded a television set.

Viktor Pavlyk, on skates and in an opera hat, was a guest star in the maitre nomination. A ten-year-old girl sitting next to me in the audience pointed out, correctly, that the man proved more relaxed onstage than Vlasova. Seeing his pink silk shirt, one felt like getting some black ink and crying. And when he started going through the motions of playing a bass guitar, plucking Michael Jackson’s way, media people in the audience responded by giggling. Then he summoned a female dancer from the audience, clad in red (a festival participant), to join him onstage. Rather than stand by the star and melt, basking in his glory, she made a decent corps de ballet job. Everybody liked Pavlyk.

Another really good discovery was a kind of grand parade performed by all of the dance competitors. It was a dynamic sparkling show, adding to the festive mood. Actually, the parade was the festival’s closing ceremony, the whole thing ending in ostensably dazzling fireworks.

CONCLUSIONS

Disregarding the great amount of irony concerning certain aspects of the festival, it has been and will remain the biggest hope in the Ukrainian world of children’s songs and dance. It is only here that children can step out on the big stage, however shaky and temporary, one which is so very important for all creative individuals. This is an opportunity for one to believe one’s creative potential, that what one is doing is actually necessary; this can prompt others to try something new. One thing remaining to explained is the usage of the modifier charitable in the title, since free participation and cheap gifts can hardly be referred to that category. This desecrates the very notion of charity. Let’s just say Black Sea Games Festival. This sounds proud and true. Games, indeed. Games for all, ranging from the organizing committee to competitors to audiences. Games adding to and actually making complete another game known as life.