He was born to a Russian-speaking family in Makiivka but spent almost all his lifetime in Lviv. He combined in his oeuvre these parts of Ukraine, so dear to his heart, which not too clever politicians are trying to tear apart.

In textbooks on the history of 20th-century Ukrainian and world culture and basic esthetics, his name occurs next to such outstanding expressionists as the Norwegian Edvard Munch, the Frenchman Georges Rouault, the brilliant Austrian Arnulf Rainer, and surrealists – the French Andre Breton, the Spaniard Salvador Dali, and the Belgian Rene Magritte.

Art historians have identified his special style of painting as “Slavic branch” of European expressionism.

The well-known artist and brilliant teacher Karlo Zvirynsky said he was “a unique artist. I have seen nothing of the sort in the world painting.” He is called the Ukrainian Picasso. But in reality he was just Ukrainian. The capability of a Deed, the protesting power of true art, and the necessity to take part in public rallies are the main points in the last interview with Oleh MINKO who actively supported the “language protests” but departed this life two days before the European Square rallies.”

Mr. Minko, your colleague, the well-known painter Liubomyr Medvid, said about you: “Oleh Minko is one of the very few upright-standing people.” We saw during the latest protest actions that there were really very few of them. Why? For it is not 1937 now, not even the 1960s-1970s, when you could end up in a prison camp for having your own persuasions, wearing an embroidered shirt, or speaking Ukrainian…

“I will not sound original if I say that the main cause is tremendous disappointment after the Orange Revolution. People are indifferent and do not trust the leaders on which they used to pin great hopes, they are confused… Look at what is going on in society: corruption, mendacity of politicians, concern for their own pockets rather than for ordinary people and the state.

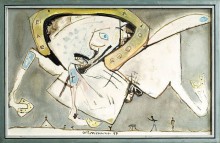

BANDURA PLAYER, 1989 ONE WHO SWALLOWS AN APPLE, 1968

“Besides, society has always been short of the people capable of making a DEED and offering RESISTANCE. Add fear to this – it is still alive, unfortunately, in our people after all the famines, genocide, and prison camps. Things like these never vanish without leaving a trace. We also have some new vivid instances, when this fear is on the rise. What has happened to Yulia Tymoshenko, Yurii Lutsenko, Valerii Ivashchenko... This could have also awaited Bohdan Danylyshyn, Mykhailo Pozhyvanov, and Andrii Shkil if they had not gone away in time.”

And were you afraid in your time? When you did not paint the way the Party demanded, refused to depict the victorious march to communism and glorify the winners of socialist emulation, such as dairymaids, tractor drivers, etc.? I was told that whenever your art confreres, including Roman Petruk, Viacheslav Chornovil, Ihor and Iryna Kalynets, the brothers Horyn, Lesia and Ruslan Gongadze [parents of Heorhii Gongadze. – Ed.], and Ivan Svitlychny from Kyiv gathered in your New Lviv apartment, you deliberately teased the KGB men who kept watch under your balcony.

“You see, it would be insincere to say that I was not afraid at all. For we had so much real-life, rather than hearsay, experience… My friend Bohdan Soroka’s father, [graphic artist] Mykhailo, had spent more than 30 years in Soviet prison camps, his mother, Kateryna Zarytska, had also served a 25-year term. And Bohdan himself was born in prison.

“There was perhaps some youthful adventurism and bravado in my behavior, but I most often had a wish to snub, take for a ride, and annoy the totalitarian regime’s gung-ho servants who always stayed hidden in the shrubs, searched the apartment when we were out, eavesdropped on, shadowed, and sent snitchers to us. Everybody was afraid in one way or another. When Bohdan Soroka and I came to attend the trial of Viacheslav Chornovil [in 1967], there were very few people there: Ihor and Iryna Kalynets, Ivan Dziuba, Alla Horska, Lina Kostenko, Ivan Drach, and Nadia Svitlychna who had come from Kyiv.

“Others were afraid of being listed as nationalists. I was worried not so much about myself as about my family. And, frankly speaking, I was also afraid, but the feeling of solidarity with Chornovil overweighed my fear. Naturally, I did not want to end up in jail, for I knew that people were quickly losing their health and eyesight there, and I was an artist! By that moment I had not yet accomplished my mission on this earth. In other words, some people, such as Stepan Bandera or Roman Shukhevych, regard struggle as their life mission, but I am neither a fighter, nor a tribune, nor a politician. I am an artist, and I have a different mission.”

To fight by means of art, while the majority were adapting, keeping silent, and collaborating with the authorities? Incidentally, you have a metaphorical picture Silence.

“Indeed, I was trying to fight by means of art. But it was far from easy to do so. I was labeled as nationalist for a series of historical pictures: A Cossack, The Death of a Cossack Commander, Trypillia, and Bandura Player. The KGB put on the heat, began to summon me for ‘crime-prevention lectures’ and issue threats. For a series of abstract pictures, I was accused of ‘blindly aping the West,’ and it was secretly forbidden to exhibit my pictures. And what does it mean for an artist not to be able to exhibit his works? Is there a more severe punishment? Yet I tried to go on speaking in a language of metaphors, symbols, in Aesopian language, hoping that people would understand me.

“The picture Mindlessness embodies the mindless authorities, their antinational laws and misdeeds. Unfortunately, it is still topical now. The Scared Horse has a yoke, rather than a harness and a saddle, on. This personifies enslavement of the Ukrainian people who have been wearing a centuries-old yoke imposed first by the Russian Empire, then by the communists, and now, in independent Ukraine, by politicians and oligarchs. And although I was lucky not to get to a prison camp, I still had to pay for my stand with almost a decade-long spiritual crisis. The arrest of my friends Chornovil, Kalynets, and Svitlychny, reprisals and the mounting KGB pressure stirred up a heavy psychological breakdown and a terrible professional crisis in me, when I could not live a normal life or paint.”

The somewhat deformed outlines of a body, the closed eyes of a man with a customary Ukrainian apple, not a brutal gag, in the mouth. This kind of “apples” hindered somebody, but somebody else got used to them – it is your metaphorical picture, One who Swallows an Apple, which is consonant with the realities of today. What scares me personally is the fact that many people who feel it easier to keep silent today and live by the principle “I don’t care,” do not understand that we may all wake up tomorrow with a gag in the mouth.

“Unfortunately, indifference is a sworn enemy of the Ukrainians. Indeed, many of our compatriots do not understand that if we have been robbed of our language today and we have resigned ourselves to this, tomorrow we will be robbed of FREEDOM! But this is the case of not only the grassroots. When, two years ago, I urged the Academic Board of the Lviv Academy of Arts, where I work, to support the students who protested against [Education Minister Dmytro] Tabachnyk, nobody backed me! Only in the corridor after the session, one professor shook my hand and thus approved of my action. He didn’t want anybody to see him do this!

“For me, independence in art and freedom is the most important thing. Whatever the circumstances, I have always been saying: my freedom will remain behind with me! As Lina Kostenko said, ‘we are no longer in the period when we had to fight for every gulp of freedom, for the right to be Ukrainian.’ So I find it difficult to understand the people who can put up with what is going on in society today.”

Svitlana Yeremenko is a journalist and author of the book Oleh Minko: Painting as a Prayer