The history of the title of People’s Artist roots back to 1943. Namely then it was granted for the first time to four artists: Alexander Gerasimov, whose pictures frequently depicted the Soviet and Communist party history, one of the most zealous adherers of socialist realism Boris Ioganson, Sergey Merkurov, who authors numerous Stalin monuments, and Vera Mukhina, who created the well-known A Worker and Collective Farmer. All the laureates are without exception winners of the Stalin Prize. Clearly, they were granted the title for the correct ideological orientation of their creative work.

Since then hundreds of artists have been granted the title of People’s Artist. After Ukraine gained independence the practice did not cease. Maybe the reason is that simply nobody could invent new gauges in the independent sovereign state to distinguish talented artists. The title is still granted, by the president’s edict. Naturally, like many other Soviet rudiments, such titles are perceived in our society in quite an ambiguous way, to be more exact, with hardly hidden skepticism.

The exhibit “People’s Artists” launched at the Ukrainian Home on the eve of Independence Day is an attempt to view the history of the title without admiration or contempt, but, say, with well-weighed interest of a researcher, to see who was awarded and for what merits.

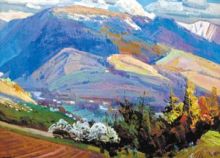

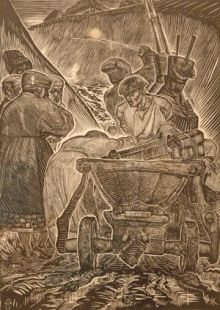

The exposition includes the works from museums, galleries, and private collections and comprises 200 items: paintings, graphic works, and sculptures. The chronology embraces the period from the 1920s and 1930s till present time. According to the organizers, the topic of the works was the main criterion to select them: to some extent they all relate to Ukraine, its history, folkways, nature, and outstanding personalities. In particular, it features the works of the classics of Ukrainian art: Vasyl Kostetsky, Mykhailo Derehus, Fedir Manailo, Tetiana Yablonska, Maria Prymachenko, Ivan Marchuk, and Hryhorii Yakutovych.

The head of the Academy of Arts of Ukraine, AMU academician Andrii Chebykin, whose graphic works are also on display at the exhibit, does not perceive the title of People’s Artist as a rudiment. “Britain has titles of lord, peer, which are granted even to football players. And in the years of independence nothing better has been invented to praise the mastery of an artist. Therefore the title of People’s Artist is no rudiment,” Chebykin considers.

Besides, unfortunately, as experience proves, sometimes neither knowledge, nor recognition is able to save the Ukrainian artists from hardships and trials, like eviction from art studios, for which the authorities find a more profitable usage. And the question is not about titles, but the way to protect artists and provide creative independence for them.

However, the interaction of artists with the society and state has never been simple, especially in the Soviet time. And the exhibition in the Ukrainian Home is proof of this. It also explains that like the history of the 20th century, its typical phenomena (including art) need thousands of footnotes, remarks, extensive interpretations, and commentaries. Context and underlying message should be comprehended in Soviet art. And first and foremost it needs truthful information coverage, because the art was created in the time of absolute lies and hypocrisy.

In the meanwhile this artistic heritage has not been studied in an appropriate way and considered at a social level. Who were all these artists? Why did they create these works? Under what historical circumstances? Could their works be different?

You can understand the ambiguity of the Soviet time when you see, for example, a portrait of Oles Honchar by Bielsky. The writer is depicted there with bookshelves in the background. You can see Guide-on Bearers and Tronka among the books, and Shevchenko’s portrait on the desk next to him. His jacket’s lapel has Soviet decorations, which cannot be identified by my generation.

The exhibit in the Ukrainian Home raises numerous questions, and there are no simple answers to them, but they need a broad public discussion, conferences, and publications in the press. However, the first most important step has been made, the question has been uttered.

The exhibit in Ukrainian Home will last until September 4.