If you look up this internationally acclaimed Ukrainian Polish expert on the Byzantine Empire in the Ukrainian Google, you will end up looking at several references, including Radio Liberty, the periodical Yi, and of course, Wikipedia. However, apart from narrow academic circles, most Ukrainians, even scholars and journalists, know practically nothing about this man. Meanwhile, his life story could well be regarded as a matter of national pride.

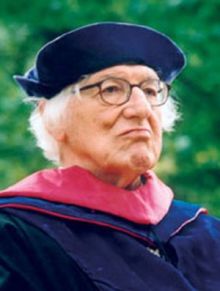

As a scholar of world caliber, Ihor Shevchenko [Igor Szewczenko in Polish – Ed.] is one of few Ukrainians to have become a lecturer at such leading US universities as Harvard, Columbia, and Princeton. He is a doctor honoris causa of the Warsaw and Lublin universities, member of the Academy of Learning (Polska Akademia Umiejetnosci) in Krakow (in fact, he and Yaroslav Isaievych [Jaroslaw Isajewicz] are the only Ukrainians to hold this status). As for his knowledge of languages, he is often referred to as a second Ahatanhel Krymsky [a prominent linguist and Orientalist, expert in over 30 languages. — Ed.]. In post-Soviet Poland, the Ukrainian Shevchenko was revered as a living legend before he died slightly more than a year ago.

Not so long ago, Lukasz Jasina, a noted Polish cultural researcher and film critic, formerly Ihor Shevchenko’s Harvard postgraduate student, published the book Enrooted Cosmopolite about Shevchenko. It is the latest publication dedicated to the scholar. In commemoration of Dr. Shevchenko’s 91st anniversary (February 10), the journal Ukrainsky tyzhden, in collaboration with the Ye Bookstore, organized a meeting with Jasina, in the course of which his book was launched. Below are what these editors believe were the most interesting facts.

BORN IN VIRTUAL UKRAINE

Even though the title of this book implies a degree of internationalism, Ihor Shevchenko, whose parents lived in Kyiv, was always proud of his forefathers in Naddniprianshchyna (Dnipro Ukraine). As it was, he was born in Radosc, now a small neighbor in Warsaw, where his family, branded as Petliurites, had to settle after immigrating to Poland, fleeing the Bolshevik onslaught on Ukraine. At the time, the UNR emigres in Poland enjoyed a considerably better status than that of the “local” Galician [Halychyna] Ukrainians. They weren’t treated as Untermenschen because the Polish government regarded people from the Ukrainian National Republic as potential allies in the struggle against the Soviets. Ihor Shevchenko had an opportunity to study at one of Poland’s best schools, Warsaw’s Adam Mickiewicz Lyceum (No. 4) where he mastered Polish (a subject Poles themselves consider to be rather difficult). Being a member of a Ukrainian emigre community, it was as though he were raised in a virtual Ukraine, while the actual Ukraine culture was being destroyed. In fact, Jasina’s book contains one of Ihor’s childhood recollection — of him sitting on the knees of the second UNR President, Andrii Levytsky.

AN ALL-EUROPEAN COLLEGE STUDENT

Ihor Shevchenko was blessed with a rare skill. He knew how to study and receive knowledge, something quite a few Ukrainians lack these days. He studied classical philology at the Charles University in Prague, after settling in that city at the start of the World War II. His friends in Prague were the reason behind his taking an interest in Byzantine studies. At 30, a promising researcher in the field, he took simultaneous courses at the universities of Leuven (Belgium), Paris, and Brussels. The German school was considered to top the list of Byzantine research centers in Europe. Ihor Shevchenko became its adept.

For Ukrainians, the important thing is not only Ihor Shevchenko’s international scholarly recognition (he wrote some 150 papers on the Byzantine Empire), but also his worldview and cultural stand. Both are proof of how badly Ukrainians need quality education these days.

Lukasz Jasina is convinced that Ihor Shevchenko was one of few people with absolutely modern worldviews that nonetheless embrace their ethnic roots.

Ihor Shevchenko is much better known and appreciated in Poland than in the land of his forefathers. Shortly before the USSR’s collapse, he was stunned to learn that he had become a foreign member of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR. This status meant that he was a foreigner in Ukraine. Polish publishers had started putting out his works in the 1960s, with his Byzantine studies proving especially popular (the man said that there was no need for millions to know about the experts on the Byzantine Empire, this being a narrow academic realm), including the books Poland in the History of Ukraine and Ukraine Between the East and West (the latter also published in Ukrainian in Poland). Incidentally, Ihor Shevchenko never insisted on translations; he believed that those interested enough would learn the language of the original.

Not coincidentally, Ihor Shevchenko is compared to Ahatanhel Krymsky. He had a fluent command of Ukrainian and Polish. He spoke Russian, although he preferred English when communicating with Russians. While in Ukraine, he spoke Ukrainian. He had also mastered French, German, Italian, Spanish, Greek, Hebrew, and Latin. As a university student, he translated George Orwell’s Animal Farm into Ukrainian — his title read “Kolhosp tvaryn” (the direct meaning is “Animal Collective Farm”). He studied English while putting together a Polish-Ukrainian-English dictionary. At 84 years of age, it would take Ihor Shevchenko 48 hours to translate 36 pages in an ancient language, along with footnotes.

He attached a great deal of importance to the relations between Ukraine and Poland. He believed that the two peoples were very close. At the same time, he addressed sharp criticism at both. In Krakow, his criticism was met with applause, but Lviv remained silent. His attitude to Ukraine was always extremely emotional. At Harvard, jointly with Omeljan Pritsak, he founded the Ukrainian Research Institute. He first visited Ukraine in 1970, then in 1990. He was happy to hear Ukrainian spoken on Kyiv’s streets, but worried about Ukraine often failing to move in the right direction of progress, about the possibility of its politicians reducing to nil, within a decade, the efforts of preceding generations. He believed the biggest problem with Ukrainians was their Soviet mentality, that it was still there. Europe refused to accept Ukraine as an equal member of the community of nations. Add here the skillful approach to the situation on the part of the “outstanding modern politician,” Vladimir Putin. How are these problems to be solved? An answer can be found in Ihor Shevchenko’s lifelong public stand.