He fitted into the phenomenology of the Ukrainian spirit as a bright, titanic personality, an artist who reflected in his painting images in a talented manner the impressive dialogues with life, full of dramatic emotions, bitterness and at the same time, passionate infatuation with earthy, sensual beauty of the world. In the Ukrainian art of the early 20th century he practically represents a rather rare, fostered by the time on the verge of two centuries, kind of a visionary artist who created large-scale, in terms of idea, symbolic canvases. This feature of Novakisvsky’s creative work is especially precious and interesting for us today, in the time of an aggressive advance of globalization, which makes everything faceless, and the art is by far the only field of the national-cultural self-assertion of the people.

The name of the Lviv exhibit is no accidental. The image of a woman takes an important place in the oeuvre of Novakivsky, who graduated from the Cracow Academy of Arts (1891-1900), shaped in the atmosphere of Art Nouveau, Symbolism, and Neo-Romanticism’s aesthetic ideals, which were reigning in Cracow in the literary-artistic circles of “Young Poland.” For Novakivsky, like for many artists of that epoch, the image of a woman was a favorite means of poetic allegory, a kind of an instrument in personification of the most complicated philosophical world outlook meanings of that time. In this sense the female images created by Novakivsky can be put in one line with the works of such outstanding European contemporaries of his as Norwegian Edward Munch, German Franz Stuck, Austrian Ferdinand Khnopff. At the same time, Novakivsky brought quite a new intonation, colored with a bright national peculiarity into the interpretation of a woman’s image, and gave to his images a more large-scale heroic-patriotic sounding, which was topical under the complicated circumstances of the sociopolitical and then the armed struggle of the Galician Ukrainians for their national identity and independent statehood. In a number of his works the woman embodies the combined image of Ukraine and is a symbol of ethno-cultural and spiritual community of the people. So, the monumental allegorical canvases he executed for the Lviv-based Lysenko Music Institute depict Ukraine as a wise mother-educator, who encourages her people to study. In a series of his large program canvases dedicated to the topic “Awakening” the central figure of the woman personifies Ukraine, resurrecting from the ages-long enslavement and spiritual dream (Awakening with a Cross in the Background), rising above the drama of historical defeats (Awakening with Revolution in the Background) and the darkness of the submissiveness of a slave (Awakening with the Dungeon in the Background) up to the high human ideals (Awakening with an Altar in the Background). Like in Shevchenko’s poems, Ukraine in Novakivsky’s works is often depicted as a hapless, long-suffering mother, who mourns over her hero sons, who died in the battles for the independent Ukrainian statehood (Surviving the World War, Ukrainian Mater Dolorosa). Other works by the artist depict it as a protecting mother, who protects her children in her embrace, before the threat of the future world cataclysm, which the artist with his prophetic far-sightedness foresaw back in the 1930s (A Flood).

In a number of the works that are on display in the exhibit (Lost Expectations. Liberation; Awakening with Images in the Background; Leda; Dzvinka) Novakivsky proves himself as a thinker, who seeks to embody in his canvases the grand world of invisible spiritual senses, raising in his symbolic-allegorical compositions the philosophical existential problems, quite a new topic for Galicia back at that time. For example, in his composition Lost Expectations. Liberation, where he depicted himself and his wife Anna-Maria in a moment of despair over a child’s coffin, the artist brings his personal story to the level of a great symbol, he asserts the spiritual power of a creative personality, his victory over the tragic blows of destiny and the eternal drama of existence. The philosophical subtext can be found also in the composition Dzvinka. This heroine of a Hutsul legend, who was in love with the people’s avenger Oleksa Dovbush and caused his tragic death, a woman with an unsure smile, like Mona Lisa’s, is interpreted by the artist as a seducing yet betraying attraction of life. In such works as Two Old Women Pondering Their Death, A Mermaid, Novakivsky is seemingly eager to peep into the hidden depth of women’s soul, show its hidden existential fears. To express in his painting images this invisible spiritual sense, he used in some cases the tense expressiveness of shapes and nervous flourishing of color strokes, and in other cases – the means of allegory.

The exhibit also shows the numerous women’s portraits Novakivsky eagerly painted for his whole life. He mostly depicted the women of his nearest surrounding or simply the admirers of his talent, intelligent Galician women. One can easily trace the peculiarities of the artist’s painting style at various stages of his creative work. The strong realistic plastic of shapes, restrained colors and thorough psychological characteristics are typical of the earliest portraits he painted in the early 1990s (Duchess Kviletska’s Portrait, Leshchynska at the Piano). However, the sketches he drew from life (L. Vohulska’s Portrait, A Woman in the Garden) show noticeable interest of the artist in the impressionistic purity of colors and light effects. These works enchant with the freshness of spontaneous perception of the model. But the artist’s later portraits (the 1930s) show reinforced expressiveness of the shapes and powerful element of color strokes, which seem to become a symbolic record of the author’s idea of the work (Kovalchuk’s Portrait, A Dairymaid, etc.).

The artist painted with especial love the numerous portraits of his wife Anna-Maria. She was his favorite model and a heroine of many compositions (Koliada, Thoughtful, etc.) Via her image the artist brings the image of a woman to a high pedestal, as a symbol of soul beauty, moral purity, and tenderness of feelings. In her image the artist glorifies the beauty of maternity, depicts her as his muse, devoted wife and mother of his children (Music, sketches An Angel of Life over the Country of Death, Self-Portrait with Wife and Son). On the whole, the works dedicated to Anna-Maria’s image are one of the most enchanting pages in Novakivsky’s oeuvre.

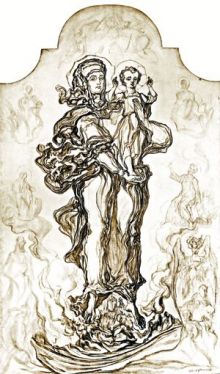

Novakivsky’s last magnificent chord was the work on the monumental images Mother of Goodness for the St. George Cathedral in Lviv. The exhibit shows the initial painting versions of this composition and the last preparatory drawing of huge size (3 to 1.97 meters), which remained unfinished because of the artist’s sudden death in August 1935.

He left for the future generations his last message, the magnificent composition with the Mother of God depicted as a barefoot peasant, rising above the Ukrainian land, giving her little son, Jesus, the future savior of the world, to people as a present. In Novakivsky’s original interpretation this image exceeds the limits of merely religious context, becoming a symbolic embodiment of a high spiritual-national idea.

Fedorovych-Malytska, the artist’s contemporary, wrote in 1935 that “The drawing of Madonna for St. George Cathedral, executed in coal, is not as much a sorrowful mother of the most painters we know, or ether being like those painted by Botticelli. No. This is a strong, proud and militant Mother of God, of superhuman height. She radiates the dignity of a Roman matron who raised her sons as firm citizens of the Roman Empire, she radiates strength and magnificence.”