Owing to the projects “20 Years to the Dream” and “The Face of Ukraine,” people, who deserved to have their images stayed on TV for 20 years of independence, who have made it possible to speak about public television in today’s Ukraine, appeared on the TV screens finally. These people are Taras Shevchenko, Lesia Ukrainka, Hryhorii Skovoroda, Petro Sahaidachny, Kateryna Bilokur, Oleksandr Dovzhenko and others.

The Day has been working on returning these names to the Ukrainian media for 15 years. That is why the similar attempts made by First National Channel have led to the balanced partnership and solidarity on the issue of the individual’s role in Ukrainian history.

“We have been independent for only 20 years, yet our country has a rich and interesting history full of personalities and events which have influenced the world history,” says Yehor BENKENDORF, General Director of the National Television Company of Ukraine. “The project we are implementing was prepared together with the specialists from the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. The project presents even the most contradictory figures of the Ukrainian history in an impartial manner, neither denouncing nor glorifying them. This project will be interesting for both older and younger generations. It is aimed at nurturing the feeling of patriotism and pride for the country which has traveled a long road to independence. First National Channel and The Day started their cooperation for the purpose of making as many people as possible aware of this information, so that not only the audience of First National Channel but The Day’s readers as well could learn more about the historical figures and events that have influenced the development of the Ukrainian state,” Benkendorf remarks.

During the next several weeks we are going to present to The Day’s readers the continuation of the abovementioned TV projects by First National Channel. We will first tell our readers about Mykola Amosov, Kateryna Bilokur and Oleksandr Dovzhenko – people who are absolutely different at first glance but equally noble and humane. They seem to be well known to us…

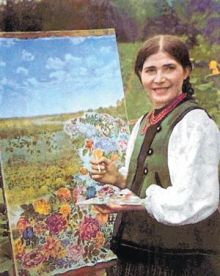

Kateryna Bilokur

“The master of dreams, visions and reveries,” “born for flowers,” “chimerical painter” whose works are “the new paganism,” “the fantastic reality or real fantasy.” All these enthusiastic reviews characterize the creative work of our compatriot, the unique self-taught painter Kateryna Bilokur. Born on December 7, 1900, in the village of Bohdanivka of Yahotyn raion (Kyiv oblast), Bilokur came from a peasant family.

Since she did not have an opportunity to go to school, she learnt reading by herself and her “primary, secondary and higher education” ended with this. Despite her parents’ desire to see her as a simple peasant doing the housework she had an overwhelming desire to become a painter. She started drawing with charcoal on a piece of cloth and gained some experience while creating sets for the village theater.

Later, Bilokur tried to get a professional education, yet her attempts to enter the Myrhorod College of the Studio Pottery were futile. Since she did not have a diploma about finishing at least a seven-year school, they refused not only to accept her but even to look at her works.

However, Bilokur continued learning the secrets of painting. She learnt painting in oils, making brushes and grounding canvases by herself. However, the world could not have gone past such a talented person even though she was hidden in a very remote place. Oksana Petrusenko played a significant role in opening her talent to the world. Bilokur heard a song by Oksana Petrusenko on the radio and wrote her a letter where she opened her heart to the singer. The destiny of the young artist moved Petrusenko and owing to the celebrity’s involvement the Poltava Folk House learnt about Bilokur and got interested in her original works. In 1940, they opened a solo exhibition of the self-taught painter from Bohdanivka.

The exhibition of only 11 works was a great success. Kateryna was awarded a trip to Moscow where she visited the Tretyakov Gallery and the Pushkin Museum. Afterwards, other famous people such as Pavlo Tychyna, Oles Honchar, Mykola Bazhan and others took care of her. The art critic Iryna Konieva called Bilokur’s genre “the floral iconography” and noticed that “the flowers in many icons radiate the light and have a halo around them.” She also paid attention to the way Bilokur painted – from the particular to the general. The artist was equally successful in other genres, too. When looking at her still lives, in particular Breakfast one can smell the rye bread, feel the sweet taste of the ripe grape bunches and apples, the delicacy of the red watermelon and the softness of tomatoes. When Pablo Picasso saw her works The Ear King, The Birch and Kolkhoz Field he got excited and called Bilokur a painter of genius. Bilokur was very successful not only in painting but also in writing, especially in writing letters and her inspired letters to different people are a striking example of this. The member of the Union of Artists, People’s Artist, Honored Art Worker of Ukraine and holder of an order, Kateryna Bilokur died on June 10, 1961, in the Yahotyn District Hospital. Despite her worldwide fame she hardly ever left her village and was true to her homeland till the end. Local people still remember her. Her family house in Bohdanivka was turned into the museum of Kateryna Bilokur. The sculpture at the museum portrays Bilokur holding a rose in her hand. In the Yahotyn Local History Museum there is a corner dedicated to Bilokur where they exhibit her photos, awards and documents. Her works in the National Ukrainian Museum always call forth admiration from numerous visitors as well as the domestic and foreign specialists. In 1989, they established the Kateryna Bilokur Prize awarded for the outstanding folk art works.

Oleksandr Dovzhenko

For 80 years now the apple orchard has been blooming, fruiting and comforting people. The orchard that not only symbolizes the artist’s overwhelming desire to renovate the earth but also serves as the moral measure of Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s stormy life and creative work.

The genius that glorified the Ukrainian cinema was born on September 10, 1894, in a large peasant family in the town of Sosnytsia in Chernihiv oblast.

He got his primary education there. In 1914, he graduated from the Hluhhiv Teachers’ Training Institute and taught Physics, Natural History, Geography, History and Gymnastics in Zhytomyr.

Then he moved to Kyiv where he studied and worked in the School of Economics at the Kyiv Commercial Institute.

Dovzhenko was also in the ranks of army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic. In August 1919, Dovzhenko came back to Zhytomyr. Shortly after the Red Army had captured the town, the Cheka [secret police. – Ed.] announced him an “enemy of the workers’ and peasants’ government” and sent him to a concentration camp for three months.

In 1921-23, he worked as a diplomat first in Warsaw and then in Berlin. In 1923, he was excluded from the party: as he explained he just did not have time to change the borotbyst party [the Ukrainian nationalist party that acted in 1918-20. – Ed.] to the communist one. He remained member of no party till the end of his life.

When Dovzhenko came back to Ukraine, he settled in Kharkiv where he worked in the newspaper Visti VUTsVK (VUTsVK stands for All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee) as an illustrator.

Odesa took a special place in Dovzhenko’s life. There, in 1926, he started his career as a film director. The Odesa Film Studio issued his first work and later the film Zvenyhora. The film about the history of the Ukrainian people triumphantly traveled all over Europe, the US and Canada.

His next work, Arsenal, is considered by most film critics to be a compromise with the government since Dovzhenko had to denounce the liberation fight of his people after the tsarist autocracy was overthrown.

In July-November 1929, Dovzhenko shot his film The Earth yet the critics immediately blamed him for the slighting presentation of the class struggle, the protection of kulaks and nostalgia for the past. The Earth, banned in Ukraine, just struck Europe. The Italian cinematographers called Dovzhenko “Homer of the Cinema.” In the Soviet Union the film was rehabilitated only in 1958 after it was chosen one of the 12 best films of world cinema at the International Referendum in Brussels.

At home Dovzhenko was blamed for nationalism and his former confederates left him. He went to Moscow and wrote a letter to Stalin asking “to protect him and help his creative development.” Stalin took up his call and Dovzhenko was ordered to make the film called The Aerograd telling about the Chukchi’s bright future.

During World War II, Dovzhenko worked as a reporter in the newspapers Chervona Armia, Krasnaia Zvezda and Izvestia. In March 1942, Izvestia published his article “Ukraine Afire.” The script of the film that Dovzhenko created “as it is and as I see the life and the sufferings of my people” who was first yielded to the enemy and then liberated from the German invaders, got the same name. At the session of the Central Committee of the National Communist Party politburo on January 31, 1944, Stalin and his confederates found the film anti-Leninist, hostile to the party and the Soviet people and contributing to “the narrow Ukrainian nationalism.”

After the war Dovzhenko shot only one full-length film Michurin at the personal Stalin’s order. The project Taras Bulba planned before the war was never realized.

Dovzhenko died on November 25, 1956, at his dacha near Moscow and was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery.

Dovzhenko’s birthday – September 10 – is celebrated in Ukraine as The Day of Cinema. According to the Decree of the Ukrainian President, on this day starting from 1994 they award the National Cinematographic Prize named after Oleksandr Dovzhenko.

Mykola Amosov

“I have lived my life not for nothing. If I could have started everything from the very beginning I would have chosen the same, the surgery.” These words belong to one of the most talented doctors of the world, the legend of the Ukrainian cardiac surgery Mykola Amosov. The future academician was born on December 6, 1913, in the village of Olkhovo in Cherepovets raion of Vologda oblast in Russia.

His mother was a midwife. Since his childhood she was for him an example of the selfless doctor’s labor and significantly influenced his final choice of the future profession. In 1939, Amosov graduated from the Arkhangelsk Medical Institute and later from the National Industrial Institute of distant learning. The qualified doctor started working as an intern of the surgical department at the Cherepovets inter-district hospital. From the very beginning of the Great Patriotic War till its victorious end Amosov was in the ranks of the Red Army working as a surgeon in the field hospitals at several fronts. As he wrote later, their “horsed hospital that had only five doctors received 40,000 injured men. None of them died from the hemorrhage.”

After the war Amosov improved his knowledge and practical surgical skills, successfully performed complicated operations on stomach, kidneys and lungs. In November 195, the Amosov family moved to Kyiv where he started working in the clinic at the Institute of Tuberculosis and Thoracic Surgery. Amosov developed the original methods of the lungs surgery; he got interested in the cardiac surgery and mastered the new field – anesthesiology – which did not exist in the USSR back then.

One of his main activities was the cardiac surgery. In 1955, he was the first in Ukraine to treat heart diseases with the help of scalpel and implemented the method of the extracorporeal circulation.

Amosov is believed to perform personally almost 6,000 heart operations. He invented his own pump oxygenator and successfully used it during the operations.

Amosov also paid great attention to the burning problems of the biological, medical and psychological cybernetics. In 1959-90, he headed the department of the Biological Cybernetics at the Hlushkov Institute of Cybernetics. In 1963, Amosov was the first in the USSR to perform the mitral valve replacement and later he was the first in the world to use the antithrombotic mitral valve prosthesis. Amosov was chosen the corresponding member of the Academy of Medical Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, he was awarded the Lenin Prize and became the deputy to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.

Amosov was the director of the Kyiv National State Institute of the Cardio-Vascular Surgery for 20 years. In 1969, he was chosen the full-fledged member of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. He successfully performed seven to eight operations a week, usually, the most complicated ones.

Under Amosov’s management, the clinic moved to the new premises and started performing up to 2,000 operations a year and almost got rid of the lines. [Standing in the line was typical of Soviet hospitals. – Ed.] In 1988, he handed his director position to his trainee. On December 12, 2002, the outstanding Ukrainian scientist died in his 90th year. He was buried at the Baikove Cemetery in Kyiv.

In 2003, they named one of the Kyiv streets after Amosov. Then the National Ukrainian Academy of Sciences established the Mykola Amosov Prize which is awarded for the significant scientific works in the field of the cardio-vascular surgery and transplantology. Amosov also left a great literary heritage. He is the author of several works known in our country and abroad: Thoughts and the Heart, The Memoirs from the Future, The Memoirs of the Field Surgeon and others.