Everybody can now see with their own eyes the shirt Stepan Bandera was wearing on the last day of his life, virtually “leaf through” the OUN Directorate’s unique documents or old foreign Ukrainian publications the only copy of which is kept in London. You do not even leave your house: all you have to do is browse a new Internet resource, the website of the London-based Ukrainian Information Service’s OUN Archive (http://ounuis.info).

The unique website was recently presented in Sumy and other cities of Ukraine (for presentation in Ternopil, see Den No. 188 of October 18). The first city was Sumy because one of the main initiators of the project was Hennadii Ivanushchenko, former director of the State Sumy Oblast Archive, who had the privilege of working for about a year with primary sources of the Ukrainian Information Service (UIS) in London. “I was astonished to see this wealth of archival documents which had until then been in fact inaccessible to anybody. The archive is now being systematized,” he says.

To make the unique OUN documents, now kept in London, accessible to the general public, it was proposed that not the archive itself but also its electronic version, a website, be established. Ivanushchenko confesses that what greatly inspired him to create this Internet resource was Den’s project Ukraine Incognita, for the latter also deals with unknown or little-known, but still important, pages of Ukraine’s history.

You have said more than once that systematizing the London-based Ukrainian Information Service’s archive is now in the focus of attention for the first time in many years.

“The archive is just beginning to be systematized. It is already under reconstruction, efforts will be made to provide for an optimal temperature and humidity as well as other conditions indispensable for an adequate upkeep of documents. But we cannot say it is a beginning as such. In a letter dated 1951, Stepan Bandera says it is necessary to create this archive, and we are now about to put his intentions into practice. Far from all can afford to travel to London and hold the archival documents in hand. This in fact brought forth an idea to establish an electronic archive. The rich documental legacy of the OUN and the related entities must be accessible to Internet users, especially taking into account Ukraine’s current circumstances. I mean the new law ‘On the National Archival Stock and Archival Institutions’ which allows destroying ‘irreparably damaged’ archival documents. It is a straight way to the ‘mopping-up of history,’ experts say. As long as this kind of laws are in force in Ukraine, I doubt that state-run archival institutions will be looking forward to receiving en masse any documents on the Ukrainian Liberation Movement from foreign archives. But still these documents should be accessible to those interested in them. Therefore, we are constantly working to digitize documents and post them on the website.”

What can a user find on your website?

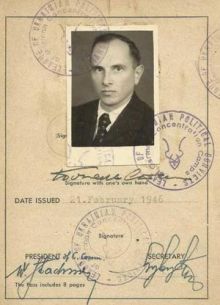

“There are sections here, where one can see not only the electronic copies of text documents on paper information carriers, but also photo-, audio-, and video-documents. A special section is an online tour of the London-based Stepan Bandera Museum of Liberation Struggle. The tours are conducted by Bandera’s comrade-in-arms Vasyl Oleskiv, and it is the OUN Leader’s grandson who gets visitors acquainted with his family.”

Please tell us about the unique documents posted on this Internet resource.

“Our electronic stocks are constantly being topped up. There is an inner card index for each item stored, which provides information on the original’s physical condition, method of reproduction, place of storage, etc. The range of themes is very broad. For example, you can read correspondence between the Ukrainian National Government and the Third Reich leadership – when the Act of Restoration of the Ukrainian State was proclaimed on June 30, 1941, and then the Germans began to carry out reprisals. There are documents on the OUN-UPA fighting against German Nazism. Unfortunately, this topic does not draw too much attention, even though a lot of little-known documents have survived. When I was in Munich, I met Professor Kosyk and saw his book on the historical events which he witnessed and took part in. One of Bandera’s comrades-in-arms took us on an excursion to the Dachau concentration camp, where he himself used to be imprisoned. There are monuments to victims of Nazism there. All countries and denominations are represented, but there is no monument to the killed Ukrainians. Why? The Dachau Prisoners Committee, where left-wingers prevailed, once decided that it was enough to mention the USSR and it was not necessary to present the Ukrainians as a separate nation. For this reason, we must tell the world about Ukraine today. There are some old books on Ukraine, which exist in one or two copies and in different languages. They shaped foreign public opinion about Ukraine a few decades ago. And then? New publications are coming out in the West today. One book, which was sold out within four days, claims that Ukraine is just an ‘intermediary option’ and will never be European. Moreover, a new batch of this book is going to be printed. It shows everything through the prism of Russian imperial interests. This is why it is necessary to tell a true history of Ukraine to the entire world, not only to the Ukrainians. The publications that used to be printed by Ukraine-friendly organizations, such as the Scottish League for European Freedom, and are in one copy only, are now getting a new lease of life.”

What is presented in the section of periodicals?

“There is a very good collection of links to the digitized archive of the newspaper Svoboda from 1898 onwards. Now the whole world can see it. This publication begins as a purely Ruthenian newspaper, and then the next waves of Ukrainian emigration brought its image in line with modern-day requirements. There is also an interesting humorous and satirical publication Mitla (Broom) (Buenos Aires, 1951-76). The language is good and refined. It turns out that some members of the Ukrainian League of Writers once went there and decided to publish this journal. Everybody – from Stalin to Brezhnev – got it hot on its pages. There is an archive of the newspaper Shliakh peremohy (The Path of Victory) established by the Stepan Bandera National Renaissance Center. The website also has some sections that comprise photographs, for example, a photo of Yaroslav Stetsko (Ukrainian Government premier in 1941), his brother Omelian and sister Oksana, a 1929 photo of a session of the OUN Territorial Executive’s Advisory Board. In a word, there are things to see. Paradoxically, while the Ukrainian authorities are trying to restrict access to the archive, the OUN is opening its documents to the general public.”

Could you draw a character sketch of those who use the newly-established Internet resource?

“First of all, I will say that once the Ukrainian Information Service’s OUN Archive has been systematized, it will also comprise a library which will be a serious rival to all those existing now. There are unique things, such as books, journals, and documents here, which cannot be found elsewhere. The website can so far be read in seven languages. I am sure it is also just the beginning. Who are we doing this for? It is, first of all, for academics who will have an opportunity now to work with primary sources without having to travel to London, and, in a broader sense, for those who are eager to search for the historical truth on their own.”