Noh is a major conservative form of classical Japanese musical drama dating back to the 14th century, based on tales with supernatural beings transformed into human form, acting as heroes narrating stories, with masks, rich costumes and stage props handed down by generations. Some Noh masks are worshipped as deities in Shinto temples, on the assumption that they contain the souls of ancient priests.

Usually on the first days of the New Year leading Noh actors perform an okina play, an ancient ritual of blessings for good luck and well-being during the year. An actor, before stepping out on stage (where he literally gropes in the dark, orienting himself by the glowing gravel marking the boundaries), undergoes a cleansing ritual with sparks from a special flint. The actor’s lines were written hundreds of years ago and the casting is rigidly determined by symbols and conventions.

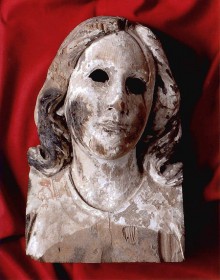

It is very hard to stage a Noh play with a modern plot. Noh posters with “Holy Mother in Nagasaki” in New York and Boston would look somewhat out of place except that the head of the wooden statue, damaged by the nuclear blast, with black holes in place of the eyes was displayed in Tokyo, in the spring of 2010.

Japanese are known for their innate sincerity and lack of official pomp when organizing the most solemn events. I’m reminded of Erica Solon’s angelic voice as she sang “Ave Maria” in the church of Waseda University, the holy relic in the hands of Bishop Takami the day before the Holy Mother started on her journey from Tokyo to the Vatican, then to Guernica (Spain) and the United States.

Two Holy Mothers were to meet in Guernica, two symbols of peace and nonviolence – the statue that had survived the massive bombing of Guernica in 1937 and one from Nagasaki. Guernica was the first city wiped out by air strikes in the history of modern wars and Nagasaki was, hopefully, the last one.

The city port of Nagasaki is the cradle of Christianity in Japan. It was here that St. Francis Xavier founded the first Christian community in Japan in the 16th century, half a century later banned by shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The latter ordered 26 Japanese Christians tortured and crucified (they were canonized on June 8, 1862, by Pope Pius IX and are listed on the calendar as Sts. Paul Miki and his Companions).

Despite the ban and severe persecution, Nagasaki Christians continued to celebrate the sacraments of baptism and prayed to the Virgin Mary before the statue of Canon, the Buddhist goddess of mercy.

After the Meiji Revolution that opened Japan to the world, the right to freedom of religion was legally confirmed. In the early 20th century St. Mary’s Cathedral was built in Nagasaki. The Spanish ambassador made a present of a statue of Our Lady of Spain to the Christian community. The statue was carved out of wood, based on the painting of the famous Bartoleme Esteban Murillo.

The Little Boy A-bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, followed by the Fat Man on Nagasaki, on August 9, 1945, killing about 100,000 people. That was the second and last nuclear attack during WW II. St. Mary’s Cathedral, one of the most impressive temples of Japan, was only 500 meters from the hypocenter [and was totally destroyed with several dozen faithful inside].

Two months later, Kaemon Noguchi, a demobilized member of the Trappist Order, visited the cathedral, rather what was left of it. He prayed to the Virgin Mary while looking around, trying to find something that belonged to the temple. Nothing. He was about to leave when his eyes fell on the blackened face of Our Lady among the debris of the altar. The rest of the wooden sculpture was destroyed and the once beautiful eyes made from stained glass had melted [other sources have it that he testified that the “crystal eyes were in the face of the ‘bombed’ Mary” when he found it].

The monk kept the relic for 30 years in his cell. In 1975 he decided to return it to the rebuilt cathedral, so the faithful could pray for peace before Her image. It became known as “Hibaku no Maria,” which means “Bombed Mary.”

Hibaku and hibakusha (lit., explosion-affected people) are the horrible neologisms of our time. Under the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law, the hibakusha fall into one of the following categories: within a few kilometers of the hypocenters of the bombs; within 2 km of the hypocenters within two weeks of the bombings; exposed to radiation from fallout; or not yet born but carried by pregnant women in any of these categories.

Over 70 years their number has dropped to some 200,000. Hibakusha are entitled to free medical treatment, but they have problems other than health. Hibakusha men and women are bad marriage propositions for fear of hereditary malfunctions in children, and they are often denied jobs. There are active hibakusha community organizations whose members combine efforts to solve common problems and disseminate information based on eyewitness accounts. Despite the horror of what happened, these people do not retreat into themselves but keep urging the world to prevent a recurrence of the tragedy.

“The people of Nagasaki prostrate themselves before God and pray: Grant that Nagasaki may be the last atomic wilderness in the history of the world,” wrote Takashi Nagai, a physician specializing in radiology, convert to Roman Catholicism, survivor of the atomic bombings who lost his wife in the blast and whose subsequent albeit brief life of prayer and service earned him the affectionate title the “Saint of Urakami” before leukemia got the better of him (he was eventually honored with the title “Servant of God,” the first step toward the Roman Catholic sainthood).

From my Soviet childhood, when information about Japan was scarce, I remember two things that had to do with that country. The first was a 45 rpm adapter in the magazine Krugozor with the “Koi-no Bakansu” by The Peanuts. The second one was Sadako and her thousand cranes (she had died of leukemia a year after my birth).

I just can’t picture anyone bowing and praying before an icon, blessing the Satan missile, probably because I can still vividly see that geta wooden sandal at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. It belonged to a 13-year-old girl by the name of Miyoko who was exposed to the bomb at her building demolition site 500 meters from the hypocenter. The only thing her mother had to remember her child by. I can’t picture anyone tearfully remembering the Soviet plombier ice cream in a waffle cup worth 19 kopecks, just as I can’t picture anyone reading the Sadako story and then forgetting all about it.

By on old ritual to overcome the “atom bomb disease” (as her mother referred to leukemia), the girl had to fold a thousand origami paper cranes. She lived to make 644, the remaining 356 were made by her schoolmates. Stunned by her death, they raised a fund to erect a monument to Sadako holding a crane. The inscription on the plaque at the foot of the statue has these simple but deep-reaching words: “This is our cry. This is our prayer. Peace on Earth.”