Recently the young Russian writer Zakhar Prilepin wrote Letter to Comrade Stalin, which was supposedly composed by the liberal community, and contains satire on this community. The letter received a colossal amount of comments and reviews in Russian information space.

In this letter Prilepin draws a distinct line between the achievements of the Soviet Union (for which he gives credit to Stalin) and the problems of modern-day Russia: “We have earned millions from factories built by your slaves and your scientists. We have led your enterprises to bankruptcy and took the money abroad, where we have built ourselves palaces. Thousands of real palaces. We have sold your icebreakers and nuclear ships and bought ourselves yachts.”

Prilepin admits Stalin’s crimes in passing: “We are almost speaking the truth when we say you did not pity Russian people and tried to exterminate them from time to time.” However, he refuses to blame Stalin for the present-day demographic situation: “We unremittingly and selflessly blame modern rapid and unceasing decrease of the population and disappearance of the nation’s aristocracy – oh, what a charming paradox! – on You! It wasn’t us who destroyed Russian farmers, Russian science, and brought Russian intellectuals down to the level of tramps and Bastardo, – don’t laugh, it is all your fault! You are to blame! You, who died 60 years ago!”

However, if there were whole generations of murdered and tortured people, demographic drops should be observed not only in every other generation. And this applies even more to the countries with a so-called demographic transition from traditional to modern type of population reproduction, which happened in the USSR during Stalin’s regime. The statistical data say that on average in the 1920s the fertility rate was six children for one woman, and in 1953 it barely reached two. Extermination of entire generations, and children in particular, in such conditions, during this transition meant the undermining of the nation’s viability for much longer than a few decades. And these drops can be observed in each generation, which is crystal clear to demographers when they look at the population pyramids (charts that break down the total population into age groups). Instead of the 600-million-strong population that Russia could be having if the tendency of the early 20th century was unbroken, now it barely has 140 million. Though Prilepin does not wish to see this – his phrases are more beautiful than reality. Not to mention the falseness of the accusations he flings at liberals, because modern Russia’s regime with all its oligarchs and “achievements” has evolved from Stalin’s creation, the NKVD.

“We say that you wanted to start a war, though we haven’t found a single documented proof of this,” writes Prilepin, turning a blind eye on the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, by which Europe was divided between the Soviet and Nazi regimes. There is a huge number of other documents. But Prilepin does not read them, he paints myths with wide strokes. “You were the leader of the country which won the most horrible war in mankind’s history,” the writer mentions justly, but he forgets to add who started that war along with Hitler.

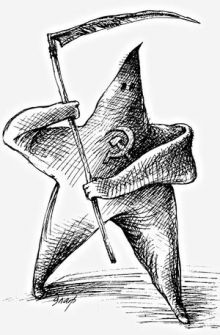

And in the end the author reveals the source of his artistic catharsis: “You (Stalin) made Russia what it had never been before – the most powerful country on earth. There has never been another empire in history as strong as Russia under your leadership.” Anyone not alien to history can easily refute this statement and remind the author of Ancient Rome, the British Empire which owned the quarter of the Earth’s dry land (this is more than just one-sixth), or the US. Yet poor command of facts is not the worst problem: the author revealed the essence of the ecstasy, so willingly shared by a large part of Russian society. The feeling of inspiring fear is much more important than the others’ lives and sometimes even more important than one’s own life. So Prilepin’s case and that of society at large is a clinical case for psychiatrists.

All this only proves the fact that history repeats itself.

Nearly 200 years ago Alexis de Tocqueville, a keen political thinker and historian, visited the US. The present political system of the States, with all its problems and drawbacks, is still being taught by his Democracy in America.

The Italian chronicler Alessandro Guagnini wrote about Muscovy: “In this realm it is mostly observed that slaves feel gratitude towards their lords, and wives towards their husbands, if they are beaten more frequently, because they take it as a sign of love. Not only servants, but also many noble, prominent men and officials are often beaten publicly and privately with sticks, by orders from the Grand Prince, and do not in the least consider it disgrace. They even boast that the monarch thus gives them the token of his love. Those who have been punished thank him, saying ‘Stay well and unharmed, our Lord, Tsar, and Grand Prince, for kindly teaching Your slave and servant with beating.”

Even before that the German diplomat and author Siegmund von Herberstein wrote: “This nation enjoys serfdom more than freedom. Lords on their deathbed tend to release their slaves, but those latter immediately give up themselves for money as slaves to other lords. If a father sells a son, and the latter is released, then the father, by his right as a sire, can sell him over and over again.” Therefore, a historian would not be surprised at Prilepin’s ideas.

It is clear that it is not Prilepin himself, with his successful PR campaign made in information society on a certainly sensational subject, who should be taken seriously. It is rather the social symptoms, revealed by him.

There is an old joke: no matter what kind of cooking pan they are trying to make at a former Soviet military plant, they will always get a Kalashnikov. Likewise, no matter what the subject of contemporary Russian political discussion is, it always turns to Stalin.

“Your name keeps itching us from the inside, and we wish you had never existed,” writes Prilepin as if addressing Stalin. The reality is in fact opposite. Not only Prilepin is tormented by the inner desire to prove his personal significance in a different, simplest (perhaps, sole) available way – through fear.

This discussion essentially shows how fast Russia is sliding back to archaic society. The country’s satellites are performing increasingly worse, yet government is holding a medieval trial of Pussy Riot. The country is becoming increasingly divided. There are fewer and fewer material and, more importantly, spiritual links. And all this happening at the background of the explosive progress of the former “third world.” It is impossible that the man who killed his citizens by the million, disrupted natural social hierarchy, twisted social atmosphere with crimes, unheard of on historical scale, should not have had a hand in the present degradation of Russia’s society. It is perhaps the colossal scale of crime that undermined the Soviet Union as a state, when millions of lives were butchered by the regime, and the remaining vast majority were bruised and held in disdain. Worshipping this example would lead the country into precipice. Surprisingly, sheer madness or die-hard national instincts make people, who claim to be Russian patriots, urge the nation to follow this path.

Oleksandr Palii is a historian, author of Kliuch do istorii Ukrainy (Key to Ukraine’s History), 2005, Istoria Ukrainy (The History of Ukraine), 2010, parliamentary candidate from the Ukrainian Platform Sobor