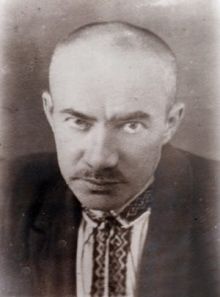

Little was known about him until recently. Those interested in the history of Podillia knew that he was a public, political, and cultural figure of the early 20th century. Lev Bazhenov’s reference book Podillia in the Works of 19th-20th-century Researchers and Ethnographers does not say much about Ipolyt Zborovsky [Hipolit Zborowski in the Polish version – Ed.]; it even says that his interests were confined to regional ethnography and museums, and there is a question mark instead of the date of death… But, as access was opened to classified archival documents, many publications about this uncommon personality have emerged in the past 15 years. Among those who wrote about him are Serhii Kot, Ludmyla Karoieva, Vitalii Rekrut, and Anatolii Stepanenko. This writer, too, was once engaged in studying his winding life path. Unlike the others, I was lucky enough not only to hold archival documents in my hands but also to deal with Zborovsky’s relatives and fellow countrymen, including those who remembered him. At my request, his daughter Maria, who now lives in Kyiv, has sent several copies of family photographs from different years. I am also personally acquainted with some of his great-grandchildren.

I think Zborovsky deserves recognition beyond his native Vinnytsia region, for he cut a larger figure — together with other trail-blazers, he launched a cooperative movement in Ukraine and was an active political and cultural figure. A Pole by birth, he became a Ukrainian by spirit, a great patriot. Unfortunately, even his home village of Yalanets failed to notice the 125th anniversary of his birth, a red-letter day in August 2010, even though there is a street here named after him, and a building which he erected in the early 20th century still serves the people.

Zborovsky was born on August 12, 1875, to the family of a noble landlord, Czeslaw Zborowski, whose manor was located in the village of Krynychky, Balt district. Ipolyt says in his Biography that his birthplace is the village of Yalanets, Olhopil district, Podillia gubernia.

He went through severe trials, beginning from childhood. Ipolyt failed to finish the Ananii Gymnasium — when he was in the 7th grade, he contracted tuberculosis of the hip joint. After treatment, Ipolyt enrolled in the Odesa Art School because he had a gift for painting. He then pursued advanced studies at a Munich art school. There is evidence that he concurrently studied at the Lviv Polytechnic Institute and was awarded a diploma of engineer. In 1901 he came back to his parents in Krynychky, where he continued self-education, studied archeology, and took a keen interest in ethnography. But he abandoned the career of an artist, for he was in the thrall of other ideas. After waiving his noble title in 1904, he left his family and “went to see the common people” — much under the influence of a poor female laborer, Frosyna Liulko, who worked for his parents. This love forced him to move to Yalanets, marry a peasant woman, and sign up for the local commune. His father’s cousin Hrushetsky, also Ipolyt by first name, demanded that his nephew be pronounced mad for this action and confined to a mental institution. The parents also opposed this marriage, but, in the course of time, they resigned themselves to their son’s choice, accepted their daughter-in-law, and even financially supported the young family. Relations also improved because of the prestige that their son was gradually acquiring in the locality.

He writes in his autobiography that he began to spread revolutionary propaganda among peasants, with ten years’ experience in this already. This means he caught the revolutionary fever as early as in the 1890s.

The revolutionary events of 1905-07 left the Podillia hinterland almost intact: rare peasant and worker protests were of economic, rather than political nature. The rural intellectual Ipolyt Zborovsky, who closely followed press reports and understood this very well, was gradually embracing the Ukrainian idea. He came to the conclusion that the implementation of the cooperative idea was an effective way to economically protect the populace. He founded a savings and loan company and a cooperative society — perhaps the first in Podillia. They were aimed at helping the populace organize themselves on the basis of cooperation and establish equitable relations between producers and consumers. This was supposed to promote the peasants’ wellbeing. In 1909 he took part in establishing the first consumer league in Bershad.

At the same time, Zborovsky begins to take part in active social life and cooperate with the press. For example, the newspaper Rada publishes articles in which he spotlights cooperative societies and offers his opinion on their further development. Naturally, he could not leave the rural realities and problems unattended: he tries to defend the Ukrainian identity and language, and cautions against the spread of drunkenness among the populace. Zborovsky was well known in Kyiv. Professor Volodymyr Antonovych, with whom Ipolyt took part in archeological excavations, highly appreciated him. Zborovsky’s research focused on history, art, ethnography, ancient monuments, and folk arts.

What Zborovsky had set up proved to be a showpiece cooperative, so he, as a cooperative movement leader in Podillia, was elected as delegate to the all-Russian congress of representatives of savings and loan associations in Saint Petersburg.

Short and slightly lame, Ipolyt always walked with a cane. He commanded profound respect from everybody. People highly esteemed his honesty, openness, and politeness. He spoke to everybody as an equal, no matter what his interlocutor’s social status was, and never displayed a cavalier attitude. Naturally, people sought advice from this wise, educated, and well-bred gentleman.

In 1911 Zborovsky began building a two-story cooperative bank.

Nastasia Hladun, a Yalanets resident born in 1907, reminisces:

“I was very little at the time, but I can remember Zborovsky once visiting my father and asking him to lend his horses to carry stones to a construction site. And when all the work was over, he found it a good idea to come and thank him, and he said he had not borrowed even a ruble for the construction.”

When Ukraine House (as Zborovsky named the structure) was built, the following line from Ivan Franko’s poetry was written on its pediment:

“Let us reunite and fraternize in an honest society!”

That was a challenge of sorts to erstwhile society and the tsarist regime. No wonder, therefore, that Zborovsky came under police surveillance and eventually ended up in jail, where he was not kept for too long.

The journal Ekonomicheskaya zhizn Podolii, No. 12, 1913, carried Masiukevych’s article “Credit Associations,” which singled out the Yalanets saving and loan association; it had started with a share capital of 611 rubles and fixed assets of 200 rubles borrowed from the State Bank. Within six years, the “honest society” expanded and had a balance of 66,595 rubles by 1913. The unit conducted mediatory operations, buying and selling farming equipment, such as plows, harrows and seeders, as well as the seeds of peas, alfalfa, and fodder beet. They also accumulated funds for rendering assistance to the families of association members in case of death or disability. Masiukevych’s article concludes with the following words:

“…in terms of size and multiplicity of its functions, the association occupies quite a conspicuous place among the credit cooperatives of Podillia gubernia. A good selection of directors and, especially, the outstanding energy and industry of the board chairman I. Zborovsky guarantee the association prosperity in the future.”

Taking into account these successes, in 1915 the congress of Podillia cooperators elected Ipolyt Zborovsky as member and deputy board chairman of the Poldillia Credit Union, leading him to temporarily move to Vinnytsia.

From his Biography:

“But here, too, I cannot escape the attention of the Yalanets priest, the Olhopil protopriest, and the Marshal of Nobility, who would not forgive me the construction of a big two-story stone house for the common people. But what struck me the most was the housing crisis, and I eventually left Vinnytsia in 1916.”

Indeed, Zborovsky’s successes, his active educational and cultural pursuits, and, besides, his being Catholic irritated the priest Afanasy and local usurers and shopkeepers. For cooperative associations were their powerful rivals. The reverend father even made his way into the consumer cooperative’s board and would incite complaints about and denunciations against Zborovsky. But numerous inspections found no infractions.

In Vinnytsia, on the advice of Prof. Mykola Bilashivsky, director of the Kyiv Applied Arts and Sciences Museum, an archeologist and ethnographer, Zborovsky joins the Union of Cities and, on the professor’s instructions, sets off to the World War II front line to be an official inspector of shops for soldiers. He combined these duties with gathering ethnographic materials and museum exhibits in the front-line area of Galicia and Bukovyna. But the situation on the battlefield worsened, and Zborovsky moves to Kyiv. In May 1917 he is elected corresponding member of the Central Committee for the Protection of Historical and Artistic Monuments. He cooperates with Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Dmytro Doroshenko, Dmytro Yavornytsky, and other well-known scholars, and is on the staff of the newspaper Nova rada.

But Zborovsky does not stay long in Kyiv — in the summer he came to his home village of Yalanets and immediately plunged into the vortex of the region’s public life. Together with his colleagues and a small group of teachers, he set up a cell of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs). He closely combined political, cultural and educational activities. The local SRs launched the newspaper Vilne slovo, spoke out for the Ukrainization of school education, and took an active part in the establishment of local government bodies.

In August 1917 the district Congress of Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies elected Zborovsky chairman of the district People’s Council, a Central Rada representation. That was a time of unrest: great efforts had to be made to prevent pogroms, spontaneous protests, looting, etc.; they were not always successful. Yet in September the district peasants’ congress elected Zborovsky a Ukrainian Central Rada delegate, and our fellow countryman took part in some of its sessions. Whenever he attended the sessions, he would meet his colleagues from the Committee for the Protection of Historical and Artistic Monuments and receive instructions to collect exhibits and organize the protection of valuable architectural and historical structures.

After the 1917 October Revolution Zborovsky was elected chairman of the district Zemstvo Council as well as delegate to the Constituent Assembly of Ukraine on the SR party ticket. But as soon as March 1918 he resigned as chairman and returned from the district center Olhopil to his home in Yalanets, where he stayed until the Hetman Skoropadsky coup, when he and his colleagues, who belonged to the Party of Socialist Revolutionaries, were arrested. He was “helped” in this by his uncle Ipolyt Hrushetsky who supplied the new authorities with false evidence against his nephew and his comrades. The arguments were really ironclad: Zborovsky allegedly organized resistance to the hetman’s government, issued leaflets, and supported the pogroms in landlords’ manors. In the whistle-blowers’ view, even the fact that Zemstvo Council documentation was typed in Ukrainian was nothing but sedition.

An Austrian drumhead court martial in Vapniarka sentenced Zborovsky to be executed by firing squad. What saved him from inevitable death was his membership in the Ukrainian Central Rada. He was taken to Kyiv’s Lukianivska Prison. Three months later his friends managed to have him released. After staying in Kyiv for some time, he came back home and worked as secretary of the Bershad Consumer Association board. He combined again his main work with collecting exhibits for a projected ethnographical museum.

In those uneasy times, when governments would change with head-spinning rapidity, Zborovsky narrowly escaped execution again — this time by Denikin’s White Army. He had to flee to Odesa, where he was in hiding under an alias at his friends’ place.

Nor did the establishment of Soviet power bring peace to Zborovsky: he was stripped of election rights and forbidden to hold elected offices. So he turned to his favorite occupation: he founded the Antonovych Scholarly Society and a museum in Bershad which he headed from 1920 to 1922.

From the Biography:

“Here, amid the roar of guns and with gangs all around, I keep collecting what is left in landlords’ estates: pictures, marble, furniture, archives. The Bershad museum is now a unit to reckon with.”

Unfortunately, nothing survived.

In 1923 Zborovsky returned to Yalanets at the villagers’ request. He established and headed a new cooperative here — a commune called Labor. Business was good: the association would issue economic loans, it had a good apiary and built a power plant that kept 125 bulbs in the peasants’ houses shining.

From a character reference issued by the Yalanets village council in 1929:

“In 1924-25, his efforts helped improve the supply of machines, which had a great impact on the agronomic cultivation of land and the increase of crop yields. Zborovsky also continues to be involved in political work. Following the behests of Lenin, Zborovsky made every effort to have our village electrified in 1924, serving as an example for the entire district.”

Our fellow countryman’s name was well known in Ukraine. In 1924 a prominent folklorist and music researcher Klyment Kvitka, Lesia Ukrainka’s husband, came to see him in the village. What the visitor saw in the commune made a strong impression on him, as did the very personality of Zborovsky; he commented on it in his travel notes.

When the Bolsheviks launched an attack on cooperative association members of non-proletarian origin and who had previously belonged to some other political parties, Zborovsky was dismissed as a “hostile element.” But, taking into account his priceless experience in ethnography, the Tulchyn Regional Executive Committee requested him to look into the museum situation in this region, and Zborovsky left his home once more. In Tulchyn he collected materials on Mykola Leontovych and 16th-18th century arms. He used even the slightest opportunity to fill the exposition with folk life items. Among them were inimitable carpets and more than 500 Easter eggs. He was also appointed director of this museum.

In Tulchyn he founded an area studies association with almost 200 members and helped save Decembrist Pavel Pestel’s house from ruination.

Zborovsky’s activities in the field of culture and his Ukrainophilia did not remain unnoticed by the new authorities. On August 26, 1929, he was arrested in the so-called SVU (Ukraine Liberation League) case.

From a character reference from the Yalanets village council, 1929:

“In 1929, when he was away and our peasants decided to switch to a communist-style economy, he continued to give good advice by correspondence. In a word, Ipolyt Zborovsky’s work in our village has been highly successful as far as socialist construction is concerned, and our residents remain grateful to him for this.”

As the political repression campaign was gaining pace at the turn of the 1930s, the Zborovskys saw their property confiscated and the head of the family was deported to Arkhangelsk on a framed-up charge of spreading counterrevolutionary literature.

After her husband’s arrest, Frosyna and their four children moved to stay with her distant relatives in Chernihiv, where she found employ at a cannery.

Three years later Zborovsky came back from exile — first to Tulchyn, where he worked in the museum, and then to Yalanets, where he worked as an agronomist at the collective farm. He was also employed for some time as an accountant at a TB clinic.

It seemed to this elderly, past-60 person that he would at last be left alone. But the bloody year of 1937 had already been striding across the Country of Soviets.

In the midsummer of that year Zborovsky suffered a stroke that left him paralyzed and bedridden. When a “Black Maria” [trucks used to carry prisoners. – Ed.] came to take him, he could not walk out by himself and was carried on a stretcher. His wife and children implored that the sick man be allowed to recover at least a little. But the loyal henchmen of the authoritarian regime did not seem to hear the words or see the tears. When one of the policemen saw a French-language book, he said: “It’s not written in our tongue, so you are an enemy of the people and a foreign spy.”

Criminal case No. 2251, still kept at the regional archive, is of a little more than 20 pages. It was opened on August 4 through 6 of the ominous year 1937. It took two days to decide on the destiny of a person, to cancel and doom to oblivion all the good he had done. Two days later, on August 8, a Vinnytsia region NKVD “troika” resolved to have Ipolyt Zborovsky executed by firing squad. The sentence was carried out as soon as August 25.

As I was looking into this case, I noticed that no evidence of “anti-Soviet agitation” was cited at all. It is clearly a frame-up. The file comprises a resume, minutes of one (!) interrogation of the defendant and of three witnesses (fabricated, as it was found later), and the bill of accusation. He was arrested without a prosecutor’s sanction or a formal indictment.

Zborovsky’s relatives did not know for more than 20 years about how and when he departed this life. His wife was notified in 1956 that he had died of cardiac arrest in 1942 in a prison camp, but that was a lie. In November 1958 Frosyna formally appealed to the USSR Prosecutor General. The answer made it possible to revise the criminal case of Zborovsky and fully rehabilitate him. The wife was given a certificate to this effect on October 1, 1959.

Frosyna was 15 years younger than her husband. The Zborovskys had two sons and two daughters. When father was arrested in 1937, Yurii had already turned 30, Viacheslav 28, Halyna 18, and Maria 14. Their destinies were quite different. Aware that nothing good was in store for them as children of an “enemy of the people” in their native place, the sons set off to Siberia on their own.

As for Halyna, she was expelled from the Young Communist League after her father’s arrest and was told to repudiate her father in a regional newspaper, but she refused to do so. She helped the partisans during World War II. She worked as a nurse in Bershad and died a few years ago. Fellow villagers supported the Zborovskys, for they knew that Ipolyt was innocent.

Ipolyt’s youngest daughter Maria, now 87, lives in Kyiv oblast, where many other descendants of the Zborovskys reside. His great-granddaughter Halyna Strutynska, a world-famous circus actress, winner of the Miss Magic title, lives with her family in Berlin.

Fortunately, gone are such ugly brands as “enemy of the people.” Virtue has been restored to an uncommon individual, Ipolyt Zborovsky, a true patriot of Ukraine and his region, a creative personality and a devotee.

Fedir Shevchuk is a journalist based in Vinnytsia oblast