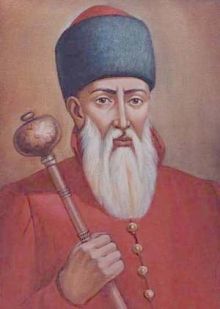

Today on the shelves of our bookstores one can easily find various Russian-language historical works, like 100 Greatest Commanders or 100 People Who Changed History. However, you won’t find Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny in these books, even though he was perhaps the best Ukrainian commander, one who won many battles. Sahaidachny was long one of the most essential figures in the historical memory of ordinary Ukrainians. This was mentioned by Mykola Hohol. However, in the 19th-20th centuries, owing to historians and even more to politicians, there was a shift of accents in the interpretation of Ukraine’s past. And Sahaidachny had to “yield” to some Cossack chiefs. Why it happened is another topic.

Nevertheless, Sahaidachny is one of the most significant and important figures in our early modern history. His activity had an immense influence on the political, military, religious and cultural situation in Ukraine in the first quarter of the 17th century. Actually, owing to him one of the biggest battles of Europe at the time was won — the Battle of Khotyn in 1621.

But before jumping in, one should say a few words about Sahaidachny and try to understand the logic of his actions. We are not sure where and when he was born. There are more or less credible assumptions as to his birthplace. The famous Poems for the Piteous Interment of Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny (1622) by Kasian Sakovych mention that the protagonist of this work was raised in the Przemysl area, in Pidhiria. The 17th century chronicler Joachim Jerlicz characterizes him as a “nobleman from around Sambir.” The Ukrainian writer Andrii Chaikovsky (1857-1935), based on a study of noble families in the Sambir area, came to the conclusion that the village of Kulchytsi could be the birthplace of Sahaidachny. This is now the dominant opinion, and the citizens of Kulchytsi believe that Sahaidachny was born exactly in their village and pay homage to this hero in many ways.

The issue of the date of birth is more complicated. The abovementioned Andrii Chaikovsky presumed that the hero of Khotyn was born around 1570 and died when he was 52 years old. However, the writer must have added an extra decade for Sahaidachny. There is some evidence that our hero appeared in Zaporizhia in the early 17th century. It was typically people below 30 who went there. At that time this was considered ripe old age.

There is one more reason to believe Sahaidachny was born in the early 1580s. The abovementioned Poems for the Piteous Interment of Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny say that their protagonist, after “childhood,” “went to Ostroh to study civil sciences, which flourished there.” From these words one can glean that he arrived at the Ostroh Academy when reaching adolescence. It is known that the academy experienced its heyday in the middle 1590s, in connection with the exacerbation of anti-Uniate polemics. At that time a printing house was active there, and a powerful circle of anti-Uniate polemists was formed.

Thus, Sahaidachny could arrive in Ostroh when he was about 15 years old, in the middle of 1590s. We may only guess why he went to study there. It would seem more logical to go to the school of the Lviv Brotherhood. However, the education of Galicians in the Ostroh Academy was a widespread practice.

Sahaidachny spent his formative years in Ostroh. There our hero had a chance to learn about the best achievements of the then Ukrainian culture, realize the importance of the Orthodox religion, with education and patronage in its flourishing. The “Ostroh trace” showed itself many times. In some sense he is a successor of the traditions of Prince Vasyl-Kostiantyn Ostrozky — both politically and spiritually.

Some authors say that Sahaidachny allegedly participated in the anti-Uniate polemics, and even wrote the work Explanations about the Union. However, this is an apocryphal — not a rarity in scholarly literature. The reason it appeared was Dmytro Bantysh-Kamensky’s free translation of a fragment from a letter written by Lev Sapiha from Warsaw to Josaphat Kuntsevych on March 12, 1622. However, there is no doubt that Sahaidachny belonged to the earnest supporters of Orthodoxy and opponents of the Union, and in this he was a follower of Prince Vasyl-Kostiantyn Ostrozky. After all, Jan Sobieski, who described the Battle of Khotyn and pointed out the significant role of Sahaidachny in it, wrote about him: “He surrounded Greek rite and religion by an unusually hot cult, more than superstitious, and he was the worst and mortal enemy for those who passed to the bosom of the Roman church.”

Sahaidachny must have had all opportunities to make a traditional nobleman’s career. Many Ostroh Academy graduates became “servants,” secular or church, in the huge possessions of Prince Vasyl-Kostiantyn Ostrozky. Volodymyr Antonovych, though not referring to any specific source, stated that Sahaidachny allegedly served for Kyiv’s judge Aksak. This seems quite probable. Let’s remember that Vasyl-Kostiantyn Ostrozky was a Kyiv voivode, and many graduates of the Ostroh Academy found themselves in Kyiv and on the territory of the Kyiv region. Volodymyr Antonovych also shows that Aksak, whom Sahaidachny served, had some family drama, implying it was the reason for Sahaidachny’s flight from Kyiv to Zaporizhia, since he was involved in it.

In Zaporizhia Sahaidachny tried to realize himself as a warrior and commander. Ukrainian Cossacks repeatedly elected him their chief. When Sahaidachny was hetman, they undertook a number of successful campaigns in the Black Sea, attacking coastal cities of the Ottoman Empire. For example, in 1610 Cossacks attacked Turkish possessions near Varna, in 1614 they undertook a sea campaign in Anatolia and assaulted the Sinop Fortress, in 1616 they attacked Kafa (Feodosia), Trapesund, Samsun, suburbs of Varna and Constanta, in 1620 they again assaulted Varna and in 1621, Sinop. This anti-Turkish activity of Sahaidachny can be regarded as a continuation of the anti-Turkish and anti-Tatar campaigns of Semerii (Severyn) Nalyvaiko, which were undertaken with the secret sanction of Vasyl-Kostiantyn Ostrozky.

Researchers have found that Cossacks sea campaigns under Sahaidachny considerably influenced politics, economics, and everyday life in the basin of the Black Sea.

There is a popular song connected to those campaigns. It contains the following lyrics:

On Sunday morning

People gathered

For a Cossack’s council

And started giving advice:

From where Varna should be taken:

From land or sea,

Or from the small river?

Andrii Chaikovsky expressed the following thoughts regarding this work: “In that song Sahaidachny is not mentioned as the one taking part in that campaign, but it seems that the author was not a Dnipro Ukraine resident, because the dialect is not specific to Dnipro Ukraine, but rather of Galicia, and from the suburbs of Stary Sambir, for one can hear this dialect there even today. Perhaps Petro Konashevych himself was its author, and therefore he doesn’t mention anything about himself.”

One should interpret Sahaidachny’s campaigns to Moldavian and volost lands in 1612-13 in the context of the anti-Turkish and anti-Tatar policy.

The campaign against Moscow in 1618 was an important moment in the commander’s life. Perhaps this “uncomfortable” fact caused Russian and then Soviet historians to suppress the deeds of Sahaidachny, deliberately moving this historical figure to the background. I will not dwell on the details of the Polish-Russian war of 1617-18. Muscovy was going through hard times, but the “Time of Troubles” would go on. The struggle for the Moscow throne was ongoing. King of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Sigismund III expected by means of military force to enthrone his son Wladyslaw. The prince was approaching Moscow with his army. However he lacked forces. Sahaidachny set off to help Wladyslaw with a Cossack army of 20,000. He raided all Severia, Yelets, Shatsk, Kolomna and other Russian towns. Near Moscow he reunited with Wladyslaw.

The united troops were to undertake a night assault against Moscow. However, it was unsuccessful. “Pious legends” remained, which wander from one edition to another, that Cossack’s hetman, once he heard the bells of churches, refused to assault Orthodox Moscow. Reality was much simpler, and there were some misunderstandings regarding the assault. Then it was canceled, as the year-long term the Sejm gave for the war with Muscovy expired. It should be noted that unlike in despotic Muscovy, in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth state affairs were solved in a democratic way. And, consequently, the Sejm’s decisions were more important than the king’s will.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth concluded a truce with Muscovy. Prince Wladyslaw refused from his claims for Moscow’s throne. However, in its turn, Muscovy ceded Chernihiv and Severia regions to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Our historians don’t pay much attention to the Moscow campaign of Sahaidachny and don’t interpret its meaning for Ukraine. Perhaps, consciously or unconsciously, the fear of the “older brother” shows up. Firstly, Sahaidachny’s raid consolidated the victory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in that war. It got the lands — Chernihiv and Severia regions, which later became Ukrainian. If it didn’t happen, these territories could become Russian, as it happened, for example, with the Belarusian Smolensk region. Secondly, the Moscow campaign of Sahaidachny formed Prince Wladyslaw’s favorable attitude to Ukrainian Cossacks. Once he became king, he made concessions for them: in particular, in 1632 he legalized the Orthodox hierarchy of Ukraine and Belarus. Actually, he finished what Sahaidachny initiated.

However, the Battle of Khotyn turned out to be Sahaidachny’s biggest victory. Its prolog is as follows. In 1618 Osman II came to power, and immediately began preparing for war with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. He hoped that by defeating this state he would consolidate his influence in Europe. The year of 1620 was tragic for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: the Turkish-Tatar army of many thousands totally defeated the Polish army headed by the crown hetman Stanislaw Zolkiewski at Tutora Fields in Moldova. The king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was hastily looking for help from European monarchs. However his hopes were in vain. Only Ukrainian Cossacks could really help the Commonwealth.

Sahaidachny made use of this situation in his own way. Together with Cossacks he did a lot for the protection of the Orthodox faith. That is why in 1615 the Kyiv Brotherhood, which became one of centers of the Orthodox movement, was founded. At that time almost no Orthodox hierarchs remained in Ukraine and Belarus, and the Uniates came to their churches. In one or two decades the Orthodox church would be completely ousted by the Uniates. Sahaidachny dared renew the Orthodox hierarchy. It happened in the following way. Taking the opportunity of the Jerusalem Patriarch Theophanus’ trip from Moscow through Ukraine, he made him consecrate bishops for the Orthodox Kyiv metropolis. This secretly happened in late 1620-early 1621. It’s interesting to note that the consecrated bishops, as a rule, were connected with the Ostroh Academy and Ostroh cultural environment. These were Iov Boretsky, Isaakii Boryskovych, Isaia Kopynsky, Iosyf Kurtsevych, and Meletii Smotrytsky. However, such a consecration, not sanctioned by the government, was considered a crime. Therefore, all the hierarchs were under Sahaidachny’s protection. After the defeat near Tutora, when the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth needed the help of the Cossack army, no one dared to meddle with them.

The issue of recognizing the Orthodox hierarchy became the subject of a kind of bargaining between Sahaidachny and King Sigismund III. The details of the political game both parties held is another topic. Sahaidachny, from all appearances, got some promises. And the Cossack’s council, which took place in the hole Sukha Dibrova in the Kyiv region in June 1621, decided to unite with the Polish-Lithuanian army to struggle against the infidels. They determined Mohyliv on Dnister as the place for the meeting. Near this fortress, a huge army was gathered from both sides. The Turkish-Tatar army, headed by Sultan Osman II, constituted about 150,000 people. It was opposed by the Polish-Lithuanian army (over 50,000 soldiers) headed by Prince Wladyslaw and the crown hetman Jan Karol Chodkiewicz. The Cossack army joined him; it had to break through, fighting against Turks and Tatars. Generally, there were a bit more than 40,000 Cossacks. As we see, the Turkish side had a quantitative advantage.

Mykhailo Hrushevsky, characterizing the Cossack army near Khotyn, wrote: “On the whole, the Cossack army that took part in the campaign, was as big as the Polish one and not worse than it: armed worse, but was not disciplined worse, and much better trained in the war with Tatars and Turks.”

Hetman Sahaidachny’s hand was wounded before the beginning of the battle in a conflict with a Turkish detachment. But he continued guiding the Cossacks anyway. Owing to his military art, the Cossack army got many victories.

The Battle of Khotyn started on September 2, 1621 with the attack of the main Turkish forces on the entire frontline. At this, the main attack was on the Cossack’s army. Cossacks had some losses. However, the next day they tried to get their revenge, making the enemy retreat. The battle of September 4 became a kind of a triumph for the Cossack’s army. The Armenian Ovanes Kamenatsi, an eyewitness of these events, describes it in the following way: “Infidel Turks came up with canons and were attacking Cossacks with small forces the entire day. But before night the Cossacks left camp and attacked the Turks, and they, failing to oppose, retreated and started fleeing. Cossacks rushed after them, destroying them, and were pursuing them up to their camp and beat many infidels, and got a lot of booty. But soon the night came and the Poles couldn’t provide support for the Cossacks. Nevertheless, the Cossacks won over six canons from the Turks, due to this the Turkish sultan with his pashas was in a big sorrow.”

Sahaidachny used the traditional Cossack tactic of night attacks. They undertook them on the night of September 6/7, 16/17, 19/20 and 22/23. About three thousand Cossacks participated in the latter, they killed a few hundred Turks, seized many weapons and valuables. On the whole the Battle of Khotyn became positional and lasted for over a month. For this time the crown hetman Jan Karol Chodkiewicz died. It happened on September 24. Turks decided to make use of the commander’s death. On September 28 Sultan Osman II ordered a full battle. However, the Turks didn’t manage to break through the defense. Then the Cossack army launched a counterattack, as a result of which the enemy retreated along the frontline. After all, Osman II, seeing the hopelessness of further military actions, agreed to conclude an agreement with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and refused from further attacking Ukraine and Poland.

Some contemporaries even say that without the Cossacks the army of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth would not have been able to hold back the Turks and would have lost the battle in a matter of days. It is notable that Prince Wladyslaw, who formally guided the troops of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth near Khotyn, highly evaluated the role of Sahaidachny in the battle. He specially presented him a golden sword with diamonds and inscription: “To Konashevych — the victor of Osman near Khotyn.”

How should the Battle of Khotyn and its results be evaluated? Mykhailo Hrushevsky wrote the following thoughts: “Guided by Sahaidachny’s iron hand, the Cossacks made from the history of the Khotyn campaign a history of incomparable exploits of courage and selflessness for the benefit and honor of the state-stepmother that filled eyewitnesses with surprise and recognition — Poles, and then us, descendants of these heroes, filled in with the mixed feeling of pride, sorrow, and shame for this servile heroism for the benefit of the master-enemy, irreconcilable-hostile regime, any assistance to which, after all, turned out to be a crime to our own national interests.”

Certainly, there is a share of truth in these meditations. Indeed, in this case the Cossacks served a state which was a stepmother for them. However, this service shouldn’t be defined as a “crime to our own national interests.” After all, speaking about new nations in Europe at that time and corresponding “national interests” is very problematic. The Battle of Khotyn was important for the civilizational choice of Ukraine and other lands of Eastern and partly Central Europe. Since it decided whether these lands would be left in the bosom of the “European Christian civilization,” which had its upheaval at that time, or would become a periphery of the Muslim world, which was about to decline. Sahaidachny, despite many counterarguments, made a choice for Europe. And if Ukraine still has some European features, this is to a great degree to the merit of Sahaidachny.

Having reached the peak of glory, Sahaidachny never took advantage of the Khotyn victory. Being wounded in battle, he was sick, and died on April 20, 1622. However, after the death he also served the “Ukrainian cause.” The mentioned Poems for the Piteous Interment of Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny, which are considered to be a gem of Ukrainian poetry of that period, were written about him.