February 20 marked the 106th birth anniversary of a writer whose works were a terra incognita for many Ukrainians.

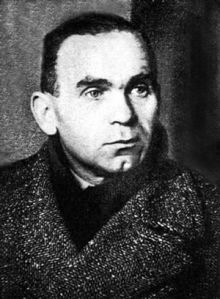

His reflections and philosophy remain very important for us — precisely why his name and works were taboo in Soviet Ukraine. Ulas Samchuk (1905-87) is the author of the three-book epic novels Volyn and Ost, and a number of other large prose works. Even though lacking in style and skeptically received by literary critics, the strength of these works is in their author’s keenness of observation, in his predominant ideological and philosophical stand.

Ulas Samchuk was born in Derman, a village not far from Ostroh. Despite all the political turmoil, the populace persisted in upholding their predominantly Ukrainian folkways. Samchuk spent his youth in Derman. When he was eight years old, family moved to Tyliavka, a village in the vicinity of the town of Shumsk, because there they could purchase a plot at a relatively low price.

His was a well-to-do peasant family, a status his parents had earned the hard way. Ulas became a devout adherent of the peasant cause (which dedication is especially manifest in his epic novels), although he never idealized the situation in the countryside. He believed that the Ukrainian village had to be upgraded while preserving its cultural traditions.

He received a secondary education at a private gymnasium (high school) in Kremenets. He had been exposed to Bolshevik propaganda previously and succumbed to it as a student, as well as during the World War I. At one point he wanted go to the Soviet Union, hoping to receive a higher education there and become a Soviet writer, but he was caught trying to cross the border.

In 1927, while in the ranks of the Polish army, he deserted and fled to Germany and settled in Breslau (currently Wroclaw in Poland). He stayed there for about two years, and it was there he began turning into a “citizen of Europe.” In Breslau, he used the opportunity to familiarize himself with the achievements of the West European civilization and upgrade his education. In particular, he studied German classical philosophy. Now his idol was Immanuel Kant. Samchuk would often quote from Kant or refer to him in his works.

In 1929-41, Samchuk lived and continued to study in Czechoslovakia. He established close contacts with the local Ukrainian emigre community and finally adopted the Ukrainian nationalist stand. He collaborated with Dontsov’s Literaturno-naukovy visnyk (Literary Scientific Herald) and in the 1930s made his name as the author of the trilogy Volyn, the novels Maria, Kulak, etc.

Samchuk returned to his native Volyn when Ukraine was under Nazi occupation (1941-44). He had reliable contacts with the Ukrainian [anti-Soviet-anti-Nazi] underground movement, yet he decided to act legitimately. He sincerely believed that his initiative would benefit the Ukrainian people. He published the newspaper Vohon (Fire) in Rivne. He traveled across Ukraine, delivering public lectures, reading his works. Needless to say, he had to collaborate with the occupation authorities, yet he never failed to overlook the priority of Ukrainian national interests. This priority cost him repeated misunderstandings with Germans. At one point he was arrested, knowing he might well be next to face a German firing squad — as had so many like-minded people he knew.

After the end of WW II, Samchuk found himself in a DP camp, in West Germany. As a camp inmate, he turned out to be an able Ukrainian organizer. He helped establish the MUR (Mystetsky ukrainsky rukh [The Artistic Ukrainian Movement]). In 1948, he emigrated to Canada where he remained active as a writer and journalist. Professionally, he realized that his books and stories [about Ukraine] lacked a first-hand approach. He died in Canada. Carved in the gravestone are his full name, dates of birth and death, the title of the Volyn trilogy, and its first part, Where this River is Flowing.

Ulas Samchuk regarded belles-lettres as a form of “popular philosophy” and spoke of his own epics as a way to lay down certain philosophical ideas. He believed that life is a combined performance by all of the elements, even though some of these elements quite often turn out to be opposed to each other. He further believed that “struggle is a true phenomenon of life… it mustn’t be guided by blind instinct, as in the case of anarchy, but by conscious will, as an organizing function… I built my creative plans relying on approximately such philosophical principles. The first book of my Volyn trilogy bears the meaningful heading, Where this River is Flowing. The river of one’s fate, the river of knowledge, the river of life. I wanted all this to be voiced by children, by their fathers and mothers. I wanted this message to come from heaven and earth, from beast and bird. The second book is entitled War and Revolution. It is about struggle, about asserting one’s place on this planet. The third is entitled Father and Son. In other words, it is about continuity. These three books make up the Volyn series. They are about the land of our forefathers, about its history, about love, about the enigmatic human soul, about those of the [Ukrainian] people who are aware of the threat of being subjugated by the aggressor…”

Ulas Samchuk comments on his “late” trilogy Ost in about the same philosophical tone. Interestingly, the first part of this prose epic is entitled Moroziv Village, and the village serves as a symbol of all those “determined, business-minded, enterprising individuals” who are, nevertheless, “split up and ethnically, socially, and politically disoriented. In a sense, it was a symbol of the 20th-century Ukraine. Samchuk’s concept allowed one to see him as a proponent of Panteleimon Kulish’s “rustic philosophy.” In fact, he never idealized life in the country, although he enjoyed the scenic environs, relishing every moment in the proverbial lap of nature.

Samchuk complained, with reason, about the qua-lity of Ukrainian literature, classics included. He said it was necessary to focus on “psychology and philosophy.” He believed that the trouble with Ukrainian literature was its weak philosophical background while upholding a dubious insulted-and-humiliated ethic. He wrote that literary works in Ukrainian also markedly betrayed a one-sided approach to certain contemporary philosophical problems. In the first place, he insisted, it was manifest in terms of poetry, with its germane lyricism, emotionally warped perception of realities, when all boiled down to empathy and tearful complaints. This approach resulted in the emergence of a meek-and-downtrodden cult, along with a proud contempt for the rich and famous, forming a tendentious concept of absolute good and evil. This sensual concept of social virtues turned into a code of ethics binding to all Ukrainian literature, with the emphasis — albeit placed gradually — on a creative, state-building personality. Being oppressed [by the Russian government. – Ed.] was raised to the level of ultimate virtue. Considering that it focused on the Ukrainian countryside, the obvious inference was a division between the ideals of good and evil, with the former to be found in the villages and the latter in the cities.

Samchuk could be regarded as a progressive nationalist, with an emphasis on world culture rather than national tradition. His was a nationalism that focused on being effectively dynamic, and meant to help the Ukrainian people overcome their backwardness, raising Ukraine to a European, even global standard. Samchuk, however, believed that his philosophy didn’t fit into any clear-cut ideological pattern, nationalism included. He wrote: “Trying to define my ideological conceptions — in terms of standard notions, such as nationalism, socialism, realism, romanticism, even idealism — would be off the mark. To quote from Hryhorii Skovoroda, I have experienced no love since [my] tender years — in my case, not for such established notions as a certain doctrine. It has always seemed to me that life doesn’t have to clearly define human behavioral parameters, and that every individual is entitled to choose [an ideology] — regardless of its political coloration — which best suits this individual, and that this choice will be only a part of that individual’s requirements that are dictated by life itself.” This was Samchuk’s worldview. He also wrote: “It seemed to me that, in human as well as in Divine nature, there existed a special scale of values; therefore, choosing a single undeniable one would be contrary to that Divine and human nature.” Samchuk wanted to make a doctrine cocktail: “Conservatism plus progress; nationalism plus socialism; realism plus romanticism; materialism plus idealism — this formula offers a synthesis, a balance of all the pros and cons, of good and evil.”

In fact, Samchuk could be regarded as a postmodernist. He was prepared to recognize any doctrine as being true in its own way — as part of the ultimate truth to be found elsewhere. He rejected the idea of enforcing a doctrine as being absolutely correct, least of all by annihilating people who professed other doctrines. This appears to explain Samchuk’s ideologically tolerant attitude.

Samchuk’s philosophy was largely determined by his idea of man. Everything stated above is proof that he viewed man from different angles, although this doesn’t mean that Samchuk had certain priorities there. He clashed with socialist authors, saying that dividing people into poor and rich was far from a sufficient [argument], that it was a small and insignificant part of the ego: “Man is a product of society, indeed, yet above all, man is a creation of the Lord, with numerous sophisticated human tasks and distinctive marks. Man can be poor and rich not only materially, but also spiritually, physically, biologically. Man’s progress is influenced by a given society, geography, and above all by what we know as the spiritual environment. Our consciousness will prove its worth only when it makes us aware of all those sophisticated human interrelationships that fill the Universe with living and lifeless nature.”

Living in this diverse world, with all its varying elements, man finds himself in the epicenter of struggle. This struggle is life, “…war, this is precisely what our life is all about. Struggle is the first precondition of life…” At the same time, Samchuk gave the notion of struggle a broad range of concepts. To him, the struggle was in staying active, doing sensible things, allowing man to assert his place on the planet Earth: “… we badly need conscious, reasonable, resourceful individuals. We do. We need such individuals, nothing else. We are often told that, without capital, we will be forced to weather heavy storms. Fiddlesticks. You can’t have capital like manna; this is something you have to work hard to gain, and the rules of the game are invariably tough… We have America right under our nose, with sources of gold found at every step… Look at our roads. They are like ditches, with perilous potholes. Abyssinia is probably where you will find the likes of them. Look at our rivers. Most of them have turned into swamps denying us hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland; there is no law to correct the situation, so there is no bog reclamation. Look at our agriculture. What’s left is a handful of small primitively equipped and manned businesses.”

Samchuk wrote this years ago. Come to think of it, little if anything has changed since then. In this context, Samchuk’s concept of heroism sounds interesting: “The true heroism of life means being capable of coping with and winning under all circumstances, weathering all storms, without looking back at what was behind those circumstances. True heroism means being able to soberly assess whatever happens and then act accordingly; in other words, true heroism means an ability to retain one’s inner balance, which is the main [human] feature.” Apparently, he had in mind reasonability, rather than emotional heroism.

This kind of reasonable heroism, however, isn’t Samchuk’s ideal. He sees a true hero as having other special characteristics, namely dignity and national identity. To him, these are the hallmarks of a European personality: “You have to be aware of yourself as an individual, of being made after His image — as we were once taught to believe; you have to be aware of all your deeds. This awareness is the European’s number one commandment. Acting contrary to it would be tantamount to destroying oneself, losing the sense of existence, destroying one’s moral visage.”

In regard to national identity, Samchuk wrote that it was “… the first prerequisite to all conscious and creative efforts… A denationalized individual can’t be strong, with a strong moral backbone or wholesome character…”

Samchuk saw man as a member of a national community: “… every individual is just a link in a long national chain, the latter having no value whatsoever.” To him, the masses lacking national identity were “plebs… a faceless and tongueless crowd.”

Pondering on national identity, Samchuk was by no means a conservative or flag-waving patriot (something germane to quite a few Ukrainian political and cultural figures at the time): “…we have never needed all those pipe-dreaming characters, people who prove helpless when faced with harsh realities. We can’t rely on such people. They can be patriots, entirely decent and well-wishing, but these virtues aren’t enough to embrace our life with all of its diversified aspects. All of these well-meaning individuals are creatively ineffective, just another cliche.” Food for thought in today’s Ukraine.

Samchuk offered interesting ideas about the rural and urban lifestyles. He favored the Ukrainian peasant’s conservative attitude inasmuch as it upheld the folkways. On the other hand, such a conservative approach led to mismanagement, on the industrial and household levels. He wrote: “Our machinery often proves obsolete… We lack machine power. Our cattle is mostly horned and draft animals, of poor breed and ill-tended… Our village streets and roads are best described as marshlands or ditches, where you can hardly walk during a certain season. Hygiene is a notion hardly applicable to our countryside, due to the current, miserable conditions.”

Samchuk insisted that the Ukrainian countryside should be upgraded, raised to a European standard. He further claimed that Ukrainians should “conquer cities” if they wanted to be a full-fledged nation: “Above all, it is necessary to conquer and master our cities psychologically, for the city is the brain of the people, and we must keep this brain under control.”

He criticized the manner in which Ukrainian literature portrayed life in the countryside and in the urban areas as constructively lacking images: “For a Ukrainian poet, the Ukrainian village is where your heart will find respite,” simply because this village is on the right side, whereas any German, Turkish, even Muscovite city is on the wrong side.”

Come to think of it, this is something other than the good old friend-or-foe approach. This has to do with one’s spiritual principles, code of ethics, moral values. This is a message stating the author’s ideal ego, establishing his social, political, and managerial standards. This was his creed. By and large, it reflected his our-man philosophy.

Samchuk’s stand in the village-city conflict was obviously different from that adopted by contemporary Ukrainian literature and culture. His views — regarding Ukrainians winning the cities — sound topical today.

Another aspect of Samchuk’s anthropological view is his criticism of the Bolshevik doctrine. He avoided the temptation of communism, after being under its ideological spell for a while. He criticized the Bolsheviks mostly for their one-dimensional attitude to the man in the street, for their inability to comprehend life as a game involving a number of players: “The trouble with Communism isn’t that it exists in Marx’s Capital or in the Lenin Mausoleum on the Red Square in Moscow; the trouble is that the proponents are convinced that this offers a cure-all for the ills being sustained by humankind. This is precisely their weak point, their failure and wretchedness. By rejecting dissidents, they are rejecting themselves because they refuse to play the game of creative, civilized life by the rules. For them, there is no ultimate objective in their lives other than five-year plans, floor space, or the final solution to all problems: a bullet in the back of the head. Terror is their creed, because they believe that terror is the only way to implement their ideals. Who is there to believe in [the expediency of] terror and for how long?”

More food for political thought in today’s Ukraine.

Samchuk believed that Bolshevik practice made man a nonentity, a spiritless living being denied the sense of personal dignity. Small wonder that the Bolsheviks should be oriented toward flag-waving grand-scale projects that would ignore the human factor, all the basic human needs: “All these Bolshevik satraps were systematically, almost purposefully building their own vicious circle, in terms of cultural, civilized realities, which realities had nothing to do with Europe or Asia. This was semi-Europe and semi-Asia… A split personality complex and lifelong experience to boot… A desire to catch up with and get ahead [of the United States], build Egyptian pyramids and Chinese walls… They wanted to have a political showcase and damn the old truth about man’s daily needs, about expediency. There was no desire to make life better organized — some probably wanted to do just that, but they faced a multitude of peculiar prejudices meant to destroy in the bud all innovative ideas. They lacked the common sense found in any European man in the street, along with the conviction that everything should be done to reach a certain goal. At times, one wonders about all those large-scale [industrial] projects. Are they what we actually need, considering that we lack basic necessities and comfortable homes…”

Incidentally, there was a vivid anthropologic aspect to all such Bolshevik large-scale projects. Each was meant to impress the man in the street, to make him aware of their grandeur, and of his own expendability.

Samchuk tried to comprehend the problems facing the Ukrainian nation, the challenges this nation had to deal with in the 20th century. Obviously, this comprehension remains a priority today.