The National Museum of Ukrainian Literature is hosting an exhibit entitled “So We’ll Raise That Red Guelder Rose.” The exposition presents a collection of works from the family archives of Alla Horska and her husband, Viktor Zaretsky, provided to the Museum by their son, Oleksii Zaretsky in 1996 in commemoration of the 5th anniversary of Ukraine’s Independence. This exhibition opens a new project “Artist’s Families in the Spiritual Space of Ukraine.”

Alla Horska (1929-70) and Viktor Zaretsky (1923-90) belonged to a generation of “spiritual dissidents.” They rallied around themselves a circle of young people capable of creative and independent thinking, including Ivan Svitlychny, Vasyl Symonenko, Vasyl Stus, Borys Antonenko-Davydovych, whose portraits are presented at the exhibit.

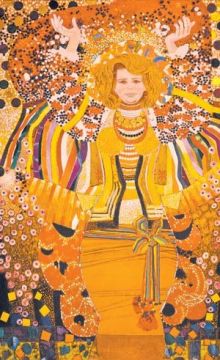

The exhibit’s title refers to Zaretsky’s eponymous portrait of Horska. This work of art attracts much attention, embodying the idea of Ukraine’s renaissance, for the sake of which she sacrificed her life. The painting impresses with its figurativeness, vividness and deep symbolism. Horska’s portrait, in bright national garments, is a guardian angel who prophesies Ukraine’s rebirth. In the Soviet time such works were not welcome, and tribute should be paid to Oleksii Zaretsky, who managed to preserve this heritage for posterity. The exposition also shows portraits of Vasyl Stus, as figuratively and skillfully embodied by the author. Borys Plaksii’s work, Alla Horska’s Portrait, is also interesting.

A total of 31 original works by Horska are presented at the exhibit: portraits of well-known people, philosophically profound self-portraits, sketches for theatrical performances (based on Mykola Kulish’s play That’s How Huska Perished, and Mykhailo Stelmakh’s novel Truth and Falsehood), a vivid series “Christmas Songs and Carols,” illustrations to Lina Kostenko’s book of poems The Stellar Integral etc. All these works of art were never exhibited before 1996, because works by Horska, as those by many other dissidents of the 1960s, had been banned.

The monumental work The Earth, created by Horska together with Zaretsky and Plaksii, is particularly interesting. Visitors can also get acquainted with the original sketch of the stained-glass window created on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Taras Shevchenko’s birthday in co-authorship with Zalyvakha, Sevruk, Semykina and Zubchenko, which was destroyed by order of the erstwhile authorities.

“A lot has been written about Alla Horska as a participant of the dissident movement of the sixties,” relates Natalia Kucher, a staff researcher at the National Museum of Ukrainian Literature. “Roman Korohodsky, in his work Dissidents of the Sixties called her ‘the soul of the Ukrainian dissident movement of the 1960s,’ because she was not simply an artist who opened Ukraine for herself and, having studied and comprehended its artistic space, joined it organically, but also one who became a spiritual leader of the creative youth of the 1960s and initiated styles and dimensions in the art that continue to be innovative today as well. The main topic of Horska’s works was Ukraine, its historical past and present-day life, its customs and traditions, its figurative symbolism and mentality — everything that constitutes the very essence of the people, the basis of their spiritual development. The artist understood that no real art can exist without it. All her works are philosophically sound, and their figurative system reveals profound meaning.”

“Alla Horska, who was brought up in a Russian-speaking environment, not only learned the Ukrainian language perfectly (her teacher was Nadia Svitlychna), but also became imbued with the Ukrainian national idea. Her talent as an artist opened up extremely wide prospects for her. She had all the necessary prerequisites for creative work and bohemian life: Alla Horska came from a well-to-do family (her father was a well-known film director) who had an apartment in downtown Kyiv; her husband was an artist well known in creative circles, a winner of the Stalin Prize…”

“Together with Les Taniuk,” continues Kucher, “the artist rallied talented people of pro-Ukrainian disposition in the Creative Youth Club Suchasnyk (The Contemporary) where like-minded ‘blood brothers’ were fervently trying to make the national idea a reality. It was a heroic deed in the former USSR, and the names of those people of invincible spirit have become legend. Thus, arose the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, which in the times of Khrushchev’s ‘thaw’ tried to bring to people’s minds a heartfelt and sincere word: ‘You know that you’re a Human. Do you know it or not?’ (Vasyl Symonenko). Alla Horska was an initiator and an active participant of this group. As everybody knows, the ‘thaw’ was followed by political repressions. She wrote letters in the defense of arrested ‘blood brothers,’ participated in court trials, and rendered assistance to the families of the accused. The well-known Protest Letter of 137 caused her expulsion from the Union of Artists of Ukraine. At that time it meant that she had forfeited her artistic career forever…”

“Only in independent Ukraine did the general public have a chance to get acquainted with her works. The artist did not bow to fate. She sold her paintings and, by holding auctions, raised funds for those in prison and their families; she sent parcels to prisons and concentration camps, gave moral support and was a model of courage and steadfastness. Opanas Zalyvakha, an artist, recalls in his letters: when Alla Horska came to see him in the Mordovian concentration camp (in 1969) to show her support, she had the air of a princess entering her possessions, so much dignity did she have, treading with pride and self-reliance; it was not just her appearance that was impressive, but also her inscrutable internal beauty and force. And so she remained in the memory of all who knew her…”

“The exhibit is interesting not only in terms of the workmanship of the skillful artist and the works dedicated to her pure image,” says Olesia Antoniuk, a designer. “It is very important that the exposition also presents the family archives — letters, memoirs, and photos. In the showcase we see the eyes of a young intellectual woman, exquisitely dressed in the fashion of the 1960s. She is both a reflection of that time and a letter addressed to the future, to us, posterity.”